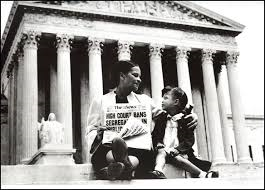

New Hampshire joined other states in adopting a tuition tax credit program in 2012; now this has been partially blocked by a ruling that illustrates how urgently the United States needs a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court doing, for legalized discrimination on the basis of religion, what Brown v. Board of Education did for legalized discrimination on the basis of race. In fact, the two institutional forms of bigotry – one adopted by Southern Democrats, the other by Northern Republicans – are intertwined historically.

The 2012 New Hampshire law allows businesses to claim credits against business taxes owed equal to 85 percent of amounts they donate to state-designated “scholarship organizations.” The organizations then award scholarships up to $2,500 to attend non-public schools or out-of-district public schools, or to defray costs of home schooling.

Opponents charge that this violates Article 83 of the state constitution, which stipulates “no money raised by taxation shall ever be granted or applied for the use of the schools of institutions of any religious sect or denomination.”

After a one-day hearing and more than six weeks of pondering, Judge John M. Lewis ruled June 17 that funds raised through tax credits were public funds (even though they had never been in government coffers), and could not be used for scholarships to religious schools. This left the door open for their use for scholarships for non-religious schools.

State Rep. Bill O’Brien, who had been House Speaker when the law was enacted, told the Manchester Union-Leader the ruling “does not address why it is permissible for the state to allow tax breaks for religious organizations through college scholarships, but it is not permissible when it’s a tax credit of this nature.”

According to the Union-Leader, “Charles Arlinghaus of the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy said, ‘The final decision in this case was always going to come from the Supreme Court, which I’m sure will uphold the law. No education tax credit has ever been struck down by a Supreme Court in any state. This ruling is particularly odd. The entire program is fine unless a parent by their own choice chooses a religious school. By this logic a program is illegal if neutral and only legal if actively hostile to religion. That’s absurd and I trust the Supreme Court will find it so.’”

Whatever the results of the appeal, it is a timely reminder of the need for a decision at the highest level to undo the lingering effects of religious discrimination in the American legal system.

The provision in the New Hampshire Constitution cited above was adopted in 1877. I provided an expert report (submitted to the court by the Institute for Justice) on the anti- Catholic bias that led to the adoption of such provisions in most state constitutions over the course of the 19th century. I showed that the public schools of New Hampshire at the time, and for decades after, were by no means neutral, but were explicitly and officially religious in curriculum and daily practices. I documented the hostility to Catholic schooling prevalent at the time, and how political leaders were determined to prevent it from becoming widely available to the children of immigrants from Ireland and Quebec who were drawn to the factories of New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

I had provided a similar report for the court in the Douglas County school voucher case in Colorado in 2011. (It’s now a chapter in my book, “American Model of State and School” (Continuum 2012)).

In the mid-1870s, Northern support for Reconstruction and the rights of freed slaves and their children waned, leading to adoption of a variety of discriminatory measures throughout the South (and indeed, though less blatantly, in the North). I tell this story in “African American/Afro-Canadian Schooling: From the Colonial Period to the Present” (Palgrave Macmillan 2011). Looking for another issue to mobilize the voters, and plagued by a reputation for corruption, Republican leaders hit upon anti-Catholicism, and concretely on the alleged threat of Catholic schooling to American democracy.

Thus the racial discrimination in education (and other spheres) mandated by law in the South was matched by religious discrimination in education mandated by law through so-called “Blaine amendments” in dozens of states.

This is not the place to trace that history, but only to note that in both cases there was what seems a clear violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Just as it required a ruling by the Supreme Court in 1954 to negate the laws providing for discrimination in access to education on the basis of race, I believe we need a Brown ruling with respect to the religious discrimination enacted in the 1870s and 1880s – in the same era and political climate that produced the Jim Crow laws. This discrimination, based on no rational principle but on religious bigotry, has made it difficult or impossible for millions of American parents to choose schools for their children that reflect their deepest convictions.

The United States is in a distinct minority among Western democracies in not providing funding for such choices as a matter of course, and the principal barrier to such even- handed justice is these unjust provisions in state constitutions across the country.

The ruling by Judge Lewis in New Hampshire – that scholarships may be awarded to children attending private,secular schools but not to those attending private, religious schools – put his thumb on the scale on the side of an understanding of life from which religion is banished. Once again we see how urgent it is to correct a fundamental injustice against Americans for whom religious perspectives are inseparable from an adequate education.

Exactly right, Charles. The decision takes a constitutional amendment born out of hostility toward Catholics and expands it to legally enshrine hostility toward all religious schools. The faulty logic declares that a tax credit or deduction is the same as an expenditure, even if the government never collected the money. If so, the longstanding property tax exemptions that religious schools enjoy should also be unconstitutional. The judge ruled that the law’s neutrality vis-a-vis religion does not suffice; it must be actively hostile. Let’s hope that the NH supreme court recognizes this decision for the absurdity that it is and overturns it.

https://www.cato.org/blog/nh-court-you-can-choose-school-so-long-its-secular

https://www.cato.org/blog/new-hampshire-courts-school-choice-decision-was-flawed-unprecedented