While getting a history degree at a small Catholic college in New Hampshire, Ben Horton figured he had two options after graduation: law school or teaching. Then, a scholarship his junior year sent him to Belfast, Ireland, where he taught at a Catholic school near the Peace Walls dividing Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. There, among the children of working-class families struggling with violence, drugs and teen pregnancy, he discovered a passion for teaching – and his faith.

“I like trying to give kids some hope, some opportunity, some guidance,’’ Horton said.

Now the 24-year-old University of Notre Dame graduate student teaches middle-schoolers at the Holy Family Catholic School in St. Petersburg, Fla. It’s part of a two-year service program developed by the Indiana university’s Alliance for Catholic Education, or ACE.

With 180 teachers nationwide, the program is similar to the bigger and better-known Teach for America, but with a faith-based twist. The goal: to train future educators specifically for Catholic schools, which are dealing with declines in enrollment and aging staff. The hope is to help revitalize those schools, so long and so proudly the cornerstone of urban education, and maybe even boost the faith itself.

“Catholic schools in a sense are the future of the church,’’ said Horton, who will finish the program in June with a master’s in education, teaching credentials and a plan to work in Catholic schools. “What ACE is doing, it’s really a noble mission because these schools serve such an important role.’’

It’s a task that comes as the country struggles to answer big questions about education, said Amy Wyskochil, director of operations for the service program and a former ACE teacher. The alliance also trains future Catholic school principals, and it partners with local dioceses to strengthen their schools’ academics, enrollment and leadership.

“Education is the most important challenge facing our country,” Wyskochil said. “Each year, millions of students fail to reach their potential because they lack access to a quality education. Catholic schools are a critical part of how we will solve our country’s educational crisis. We need talented, committed new teachers to meet that challenge by becoming Catholic school teachers.”

Horton, a lifelong Catholic school student, started teaching at Holy Family last year. The school, with 204 students in K-8, has maintained a steady enrollment thanks to a healthy parish, said Sister Flo Marino. But when veteran teachers started to retire four years ago, the superintendent signed on with ACE.

“We just felt that it was a great opportunity to have young, vibrant, interesting people taking on the job of education,’’ said Marino, the only remaining religious sister at her school. “It gives schools that opportunity to revive their programs.’’

It also provides new teachers with real classroom experience. ACE participants take intensive courses during the summer at Notre Dame. That’s followed by hands-on teaching at under-resourced Catholic schools in more than 30 cities – including six schools in the Tampa Bay area. The students receive a $12,000 stipend each year in the program, with their teacher salaries going back to the university.

Horton and seven other ACE teachers live in a rent-free house next to a neighborhood church in St. Petersburg. A former convent, the concrete-block home is furnished with simple tables, chairs and two sofas. Long hallways lead to eight tiny bedrooms, where each occupant shares one of four bathrooms with another roommate.

On a recent Monday, it was taco night. Teachers in training started arriving home shortly after 4 p.m. Some went running. Others, like Horton, changed into T-shirts and shorts, grabbed a spot on the living room couch beneath a Notre Dame banner and played video games. It was a brief respite before getting back to work grading papers, planning lessons and chopping onions.

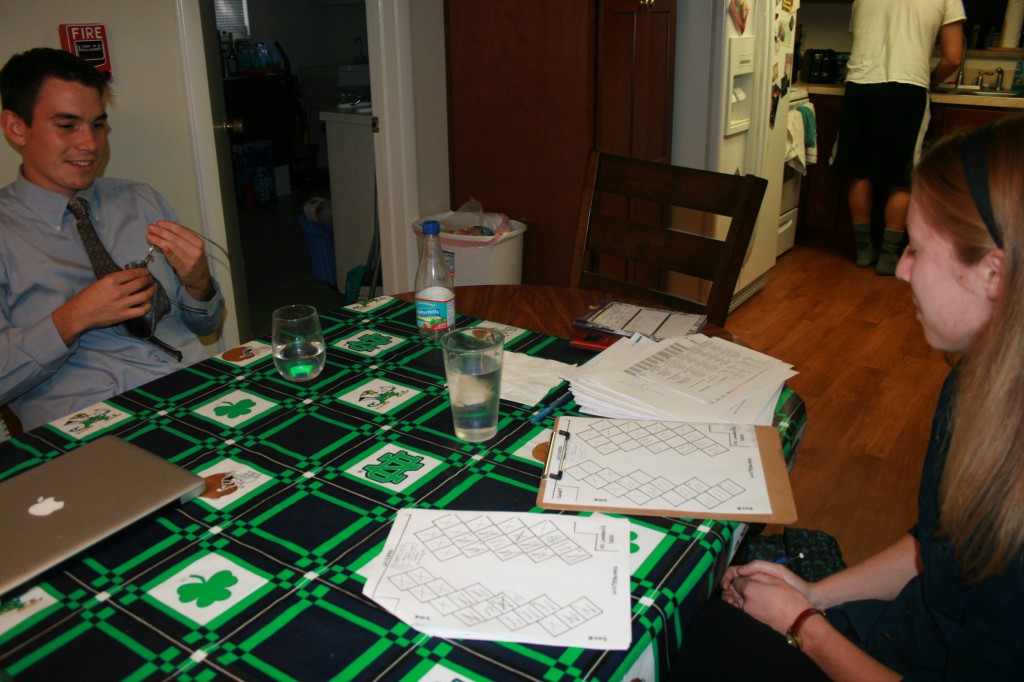

Ashley Logsdon sat at the dining room table with a classroom seating chart spread before her. The 23-year-old Ohio resident always envisioned herself as a high school science teacher, but she wasn’t sure about combining her Catholic faith and education until she got into ACE.

“I love being Catholic and I love teaching at a Catholic school because we can talk about our faith even in our science classes,’’ she said. Right now, juniors and seniors in her Advanced Placement Biology class at Tampa Catholic High School are reading “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.’’ The book has inspired some heavy discussions about stem-cell research, ethics and race.

“When I bring up topics that are controversial, I explain ‘Here’s what the science says and here’s what Catholics believe,’ ’’ she said.

Her first year was rocky. “I had a hard time learning what high school students were like,’’ said Logsdon, whose youth and long, strawberry blonde hair could help her pass as a girl in one of her classes. The high-achieving biology and theology major also struggled, for the first time in her academic career, with “learning how to fail on a regular basis.’’

ACE teachers are accepted into the program with undergraduate degrees in various fields, depending on what the schools need. For the Tampa Bay teachers, that meant degrees in math, mechanical engineering, science, Spanish and theology. There’s a lot to learn about being an instructor, including standing in front of a room full of teenagers who don’t remember to bring pencils or know enough basics to complete a lesson – and yet can smell fear.

Logsdon’s second year, so far, has been much better, she said. With more confidence and know-how, she can see a method to her mission. “I’m handing on the faith,’’ she said. “Catholic schools are a really strong vehicle for that.’’

But will she remain on that path? While Logsdon feels anchored to a Catholic school vocation, she’s headed back to Notre Dame at the end of the school year to work toward a master’s and doctoral degrees in theology. Then, who knows?

Most of ACE’s graduates – 73 percent – remain involved in education on a broader level, even if it’s just donating time or services, Wyskochil said. Of those graduates, 59 percent stay in a Catholic school.

“Many have gone on to become physicians, entrepreneurs, engineers, financial leaders, Fulbright scholars, law review editors, university professors, leaders of scholarship foundations, priests, and national science grantees,” she said. “ACE teachers continue to advocate for Catholic schools and for the needs of children in low-income communities.”

Among the Tampa Bay contingent, it’s a mixed bag. Brianna Hohman, 23, of Virginia, said she loves teaching second grade but plans to pursue another occupation – possibly physical therapy. Kaleen DeFilippis, 22, of Chicago, started teaching third-graders this year and wishes she could remain in Catholic schools. But, she said, “I don’t know if I can afford to do that.’’

Matt Cirillo hopes to stay. Standing at the kitchen counter steaming rice – it was his night to cook – he said he felt uninspired by his mechanical engineering degree. Jobs in that field seemed “kind of cookie-cutter,’’ the 23-year-old Chicagoan said. Two years teaching physics to Catholic students and coaching girls’ basketball gave him a whole new perspective. It also brought him closer to his faith, something he longs to share with his students.

Horton, the teacher at Holy Family, understands. He definitely would consider staying on at the school, with its strong sense of family and Catholic identity. “This is something I want to be a part of,” he said, “for the rest of my life.”