Antanarie Edge almost missed the chance she was hoping for. There were 60 slots for the first sixth-grade class at Florida’s first and only public boarding school, The SEED School of Miami, but 104 students had applied. When the school held a lottery to see who would get in, Antanarie was not among the lucky ones.

Then, about week into the school year, her phone rang. It was her mom. A spot had opened.

“I started jumping up and down,” she said.

Now a few months into her first year at SEED Miami, Antanarie says the reasons for her excitement have become more clear. During the week, the school is a home away from home for its students, half of them boys and half of them girls. They spend five full days eating, sleeping and attending classes in an academic oasis, a re-purposed dormitory at Florida Memorial University.

When the Miami charter school opened this fall, it became the third in a network of college-preparatory boarding schools whose model has been featured on 60 Minutes and in films like Waiting for Superman. Like existing SEED schools in Washington and Maryland, it targets some of the most disadvantaged students, for whom a seven-hour school day may not provide enough support to reach their ultimate goal: college.

Separated from the stigmas that often dog teenagers in school, students like Antanarie are free to try new things. She’s enjoyed signing up for CrossFit sessions. But above all, she’s been able to focus like never before on the goal that drove her to the school in the first place: Making it to college.

When students arrive on Sunday afternoons, they’re greeted by a row of pennants from universities, one of the many cues intended to reinforce the college-going culture that is common among no-excuses charter schools.

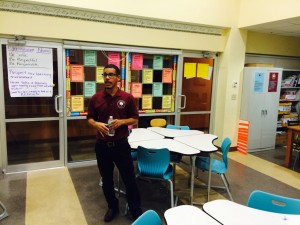

Jerico Evans, one of SEED Miami’s student life counselors, said the school wants students to believe, even in middle school, that college is a basic expectation — even if it might not be for other kids in their neighborhood.

Evans previously taught in Miami-Dade public schools and now is working toward a master’s degree in educational leadership at Johns Hopkins University. He said he’s seen this emphasis on college rub off. Before he took a job at SEED, he said, “I never met a sixth-grader who wanted to go to MIT.”

As a student life counselor, Evans works with students after the school day ends, from about 4 p.m. to midnight. He helps students with homework and leads character-education lessons. He’s also charged with making sure students read – not only during required reading time, but for class, for pleasure, to fill idle moments.

Antanarie said she’s seen a shift in her own attitude about reading.

“I used to read when I was only in the mood to read,” she said. “Now, I like reading, because it helps me learn new words.”

After student life counselors wind down their shifts, resident advisers take over through the night, and help the students prepare for class in the morning. At 8 a.m. the teachers, called professors, begin the school day.

Kara Locke, SEED Miami’s principal, said the school wanted to hire teachers like Evans who had experience in local schools.

Evans said it’s his job to make sure students are “bringing what they’re learning into the house,” the collection of adjacent dorm rooms where the group of boys he works with sleep and study after classes end. Student life counselors like Evans join professors in frequent data sessions to analyze students’ progress.

“Even if a student’s not in my house, I can have a conversation about their grades,” he said.

Students are separated by gender in their middle-school classes. As the school expands into the high school grades (it plans to add a grade level each year), the older boys and girls will work in the same classrooms.

The school aims to cultivate skills like staying on task and accepting criticism. Students can earn SEED points for upholding its values, like responsibility, respect, and compassion. They can redeem those points for perks like trips to the Miami International Auto Show.

Evans said he might never have made it to where he is now, with a degree from Temple University, if he hadn’t been sent to a boarding school in seventh grade. He had not been living up to his potential in school, he said, and his experience, brought on by a decree from his mother, taught him the importance of a nurturing environment with positive role models.

What distinguishes SEED schools from conventional boarding schools is that they’re public, and don’t charge tuition.

Schools that must be staffed 24 hours a day, five days a week, require an infusion of resources beyond those that normally flow to typical charter schools. This year’s state budget set aside $1.4 million (or slightly more than $23,000 per student) to help support SEED Miami’s operations, and the schools also rely on philanthropic support.

In addition to its charter contract with the Miami-Dade school district, state lawmakers conceived a pilot program for a public boarding school aimed at at-risk students. State law places requirements on the students who can attend. To enroll at SEED Miami, students must come from low-income families, be “at risk of academic failure,” and face other risk factors such as living in foster care or having a family member in prison.

Antanarie’s mother, Aneita Tucker, said she sought out the school after becoming concerned about whether her daughter would be able to follow three of her older siblings to college.

If she hadn’t gotten into SEED, Antanarie would be zoned to attend Norland Middle School in Miami Gardens. Tucker said traditional public schools work well for many students, but she was concerned about the distractions Edge would face, and about her ability to focus on homework while her mother worked late hours at two jobs.

“I wouldn’t call it bad,” she said of the environment at Norland. “I would call it too much hanging out.”

Now that Antanarie has been admitted into SEED, her younger brother will be able to bypass the lottery and go to school there, too.

Tucker said her daughter comes home exhausted on Fridays, and spends the weekend recharging. But she’s noticed a change in her outlook at the start of a new week.

“She can’t wait to come back on Sundays,” she said. “(She’s) like, ‘Let’s go.'”