As a spate of sudden failures has brought Florida’s charter schools under a microscope, the state’s second-largest school district stands out.

Broward County is home to more charter schools than most states. And no district in Florida has shuttered more charters that opened since the 2012-13 school year. Some of those schools foundered shortly after they opened, uprooting students and sometimes leaving the district on the hook for millions of dollars.

A review by a national organization finds the district could be doing more to curb the problem.

The report, along with a similar evaluation of neighboring Miami-Dade County, sheds new light on a sometimes-overlooked dimension of Florida’s charter school debate: The role of districts in stopping charter applicants who are not qualified to run schools.

Completed this summer by the National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) and obtained through a public records request, the review finds a “lack of rigor” in Broward’s process for reviewing charter school applications, which seemed “focused on statutory compliance rather than a quality assessment of a school’s likelihood of success.”

Leslie Brown, the district’s chief portfolio services officer, said Florida law ties authorizers’ hands. Districts might spot red flags with charter schools that want to open, but as long as an application meets all the requirements in state law, a district that says “no” risks being overturned on appeal.

“There’s a bit of a gap between what this national association includes in their principles and guidelines,” she said, and “what we have to do in Florida with regard to charter schools.”

Sudden failures have created black eyes for the state’s more than 650 charter schools, prompting calls for change from charter boosters and critics alike. The turmoil became the subject of award-winning investigations by two newspapers, including one by the South Florida Sun-Sentinel that focused largely on Broward.

Katie Piehl, NACSA’s director of authorizer development, said Florida charter schools are three times as likely as their counterparts nationally to fail within a year of opening, which has prompted her group to make the state a priority.

With few exceptions, districts are the only groups allowed to authorize charter schools in the state, which makes them the first line of defense. Piehl said district officials sometimes feel hamstrung by state law, but when it comes to weeding out weak charter applicants, some do better than others.

“You’re able to see some districts that are able to, within the confines of the existing law, make high-quality application decisions,” she said.

There are different ways to slice and dice the data on charter school failures, but Broward appears to be ground zero for the problem. It’s seen more first-and-second year closures than any other urban school district in Florida, and significantly more Miami-Dade County, its larger neighbor to the south.

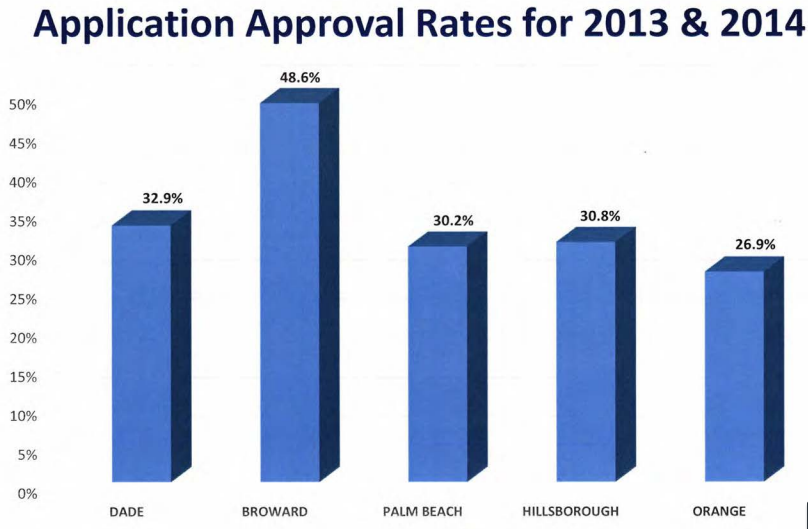

While districts are getting more stringent in their reviews of charter school applications, Broward’s approval rate remains relatively high, according to numbers state officials recently presented to a state legislative panel.

NACSA’s report acknowledges Broward’s charter school office has a small staff tasked with vetting dozens of applications and a growing portfolio of roughly 100 schools, while contending with a “seemingly ever-changing and limiting state statute.”

At the same time, it says Broward’s “current interpretation of Florida law hampers its work and creates an open- door mentality, yielding approval of applicants that then close within the first few months of operation.”

Changes in the works

Officials in Broward have pushed for changes in state law that would give them clearer authority to reject charters based on their operators’ qualifications, require charters to secure facilities well before the school year starts, and require newly opened schools to post a surety bond that can protect taxpayers if they suddenly fail.

Charter school groups and some key lawmakers say they’re willing to entertain those proposals. In the meantime, NACSA and state officials have found other ways to attack the problem.

This fall, as districts vet the latest round of charter applications, would-be operators have to disclose more information about their histories. The authorizers group has created a new tool to help districts look into their backgrounds. Earlier this year, the state awarded grants to three urban districts, including Broward, aimed at recruiting high-caliber charter networks to urban areas.

The Broward County School Board ultimately rejected its grant, but it still received the NACSA needs assessment, which was one of the add-ons. Duval and Miami-Dade Counties received similar reviews.

The review of Miami-Dade, the only Florida district with more charter schools than Broward, also found areas for improvement.

Almost across the board, though, reviewers found Miami-Dade had a stronger system for vetting charter applicants and supervising existing schools. For example, reviewers noted it requires future charters to propose a budget that assumes they’ll enroll only half as many students as they hope.

Charters sometimes propose spending plans assuming they’ll attract 1,000 students. When they wind up attracting only a few hundred, their finances can unravel rapidly —something that has happened in Broward, as recently as this school year.

In an interview, Brown, who oversees the district’s portfolio services, said the district will often challenge budget projections that seem unrealistic. But as long as the numbers add up on paper, she said, there’s little it can do.

“We can advise them but they really don’t have to listen to us,” she said. “If they can prove that their budget is viable within the application period, we cannot deny them.”

Jody Perry, who leads Broward’s charter school office, said she sometimes calls applicants who submit shoddy applications and counsels them to reconsider. “A lot of them will take our advice and go ahead and withdraw the application,” she said. The district, she added, is making other improvements, like bringing in an official from Pembroke Pines, a city that runs a municipal charter network, to help scrutinize applications.

NACSA reviewers suggested Broward look to counterparts in Miami-Dade and Hillsborough Counties, which have found ways to judge would-be operators based on their ability to run a school.

Due diligence

If someone wants to open a charter school in Hillsborough County, the process begins in the spring, when the district holds an interest meeting. The meetings, reported on earlier this year by the Tampa Bay Times, give the district a chance to size up would-be applicants and tell them what it expects.

Jenna Hodgens, the director of Hillsborough’s charter school office, said when groups do apply, experts in areas like finance and curriculum review applications, compare notes and come up with questions for a mandatory interview. People who want to open charter schools have to show up in-person and field questions — something Broward doesn’t always require, according to NACSA’s review.

“We feel that is part of due diligence: Meeting with them, looking into their past, asking them questions,” Hodgens said during a presentation to her counterparts from around the country at a conference in Colorado.

When Hillsborough finds problems, it documents them, and its decisions usually hold up on appeal. Hodgens cited the district’s rejection of a plan to open a charter school to serve MacDill Air Force Base, in which it prevailed at every stage until the plan was eventually pulled. This year, Charter Schools USA, which would have run that school, got the green light to open other schools in the district.

In a different case, Hodgens said she started calling board members listed on a charter application, and found they knew nothing of the proposed charter school they were supposedly supporting. That step, which stopped a problematic application in its tracks, wasn’t mandated in state law, but was needed to protect the public.

“The schools that are going to open in Hillsborough,” Hodgens said, “are going to impact our children.”

Download NACSA’s assessments of Broward and Miami-Dade, as well as this response from Broward.