The redefinition of public education in New Orleans — in which parental choice became widespread and most public schools were converted to charters — may have had a counter-intuitive effect. It may have increased educational stability in the city.

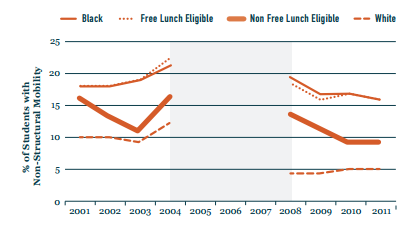

The possibility emerges from a study released last week by a team of researchers evaluating the reforms in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. By 2011, when nearly all the schools in the city had become charters, students were actually less likely to change schools, according to findings from Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance.

This could be due to housing-market changes or other hidden effects that swept over the city in the years after the storm, but the researchers point to another possible explanation: “It could be that school choice allows families to get into their preferred schools early on, so there is less need for later mobility to find better schools.”

The researchers found that school performance was a key driver of student mobility. Students in low-performing schools tended to try to leave. This tendency intensified after the state began labeling schools with letter grades based on student achievement.

For people who think market forces can lead to improvements in the education system, this should be good news. But when it came to the new schools they selected, students started to diverge. Researchers found students with high and middling test scores tended to leave lower-performing schools for higher-performing ones. Low-scoring students also tended leave lower-performing schools, but they were less likely to improve their lot by doing so. They tended to wind up in schools with comparable academic performance.

In other words, the disadvantaged students remained disadvantaged, even when they had the option to leave their low-performing schools.

The researchers offered several possible explanations. Among them:

[L]ower- and higher-performing student groups may not have equal access to information about the schools to which they transfer. Both groups have firsthand knowledge of the schools they want to leave. But families of higher-achieving students may have advantages that allow them to learn about new schools from broader social networks, visits to schools, or personal meetings with school leaders. If a lack of information is affecting the mobility of lower-performing students, then policymakers might consider additional programs that enable students from low-achieving schools to obtain firsthand knowledge of schools. Such programs could promote school visits through open houses or “shadow days,” or perhaps even facilitate meetings with current parents of the school.

Indeed, the work of some reform groups in New Orleans seems to underscore this point: When families get better information, and a little help navigating the system, they’re more likely to move to better schools.

When families get complete information, they consider more options. And when they consider more options, they are more likely to move away from underperforming schools because they feel confident that they can upgrade.

In a vacuum, school closures are a blunt instrument for creating a market for educational quality. That is not to say closures are ineffective; there’s evidence that they can have positive effects for students. But they will never be popular—or efficient.

The way to get families out of failing schools isn’t to close the doors; it’s to throw them wide open. That means investing first in family engagement when a school’s performance seems lacking. We need to support families to understand their options and decide whether their present schools are still the best place for their children.

This largely jibes with an earlier finding, also released by the Tulane research group, that disadvantaged families were less likely to choose schools based on academic quality. For those who lacked access to child care or transportation, factors like basic logistics could trump academic performance, and it was harder to shop around among multiple schools.

In particular, low-income families are less likely to own automobiles that are used for many purposes and this increases the marginal cost to families of sending their children to schools further away.

Finally, school choices might differ because low-income families are less well informed about the true characteristics of schools. With lower levels of education, they may be less able to process the information they receive. Also, if they really do have weaker preferences for education, they would be less willing to incur the cost of information gathering (e.g., visiting schools, attending school fairs, and talking with neighbors who have direct and recent school experiences). All of this may be reinforced by social networks, in which people tend to associate with and gather information from others like themselves.

In short, this is yet another sign that for school choice to fulfill its promise, parents, particularly low-income parents whose children struggle in school, will need help overcoming barriers.