If all parents had their choice of schools, schools would grow less segregated over time, and people would abandon low-performing in favor of higher-performing ones.

That’s the implication of a new study of parent preferences in the nation’s capital, where 22,000 students entered lotteries for more than 200 public schools — nearly half of them charters.

Steven Glazerman and Dallas Dotter of Mathematica Policy Research looked at parent preferences in Washington, D.C.’s new unified enrollment system for public schools, which allows parents to rank their favored schools, and assigns students to their highest-ranked school with available space.

Parents tended to prefer schools that were close to home, with high test scores, and where their students would not be racially isolated. In a predominantly African-American urban school system, parents seemed to wannt some measure of diversity in the student body.

From the study’s abstract:

The results confirm previously reported findings that commuting distance, school demographics, and academic indicators play important roles in school choice, and that there is considerable heterogeneity of preferences. Simulations suggest segregation by race and income would be reduced and enrollment in high-performing schools increased if policymakers were to expand school choice by relaxing school capacity constraints in individual campuses. The simulations also suggest that closing the lowest-performing schools could further reduce segregation and increase enrollment in high-performing schools.

The research builds on several earlier studies of school choice preferences in choice-heavy cities that, crucially, allow parents to sign up for both charter and district-run public schools through a single, unified enrollment system. Such systems are becoming more common, but have yet to be made available in Florida school districts.

There are a couple of caveats worth keeping in mind. For example, the study does not look at the preferences of parents who simply opted for their neighborhood school. And there’s a possibility that some parents — presumably, those who could afford to do so — chose schools by moving to desirable neighborhoods, a process that wouldn’t be revealed in the choice application process.

The study also finds some important differences among groups of parents. Low-income parents and parents applying to elementary schools were more likely to rely on school proficiency scores, which were available in the online portal when they applied, to judge school quality. Higher-income parents and those applying to high schools were more likely to use school accountability ratings, which provided a more nuanced picture of school performance, but weren’t available in the online system. And while they tended to gravitate to schools with strong academic indicators, parents didn’t always favor the schools that produced the largest learning gains.

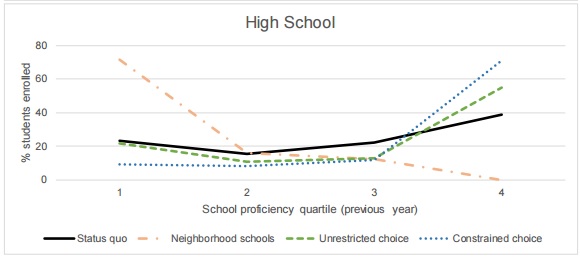

The researchers ran simulations projecting their findings into the future, showing that if parents kept picking their preferred schools, and districts made changes to accommodate their preferences (by adding space in desirable schools and allowing low-performers to close), schools would grow more racially and economically integrated, and academic low-performers would dwindle over time.

These findings point to some changes school districts could make that might benefit students under Florida’s sweeping new open-enrollment policy. If districts create unified enrollment systems that allowed parents to shop among all public schools, gave parents ready access to nuanced but easy-to-interpret information about school quality (going beyond basic proficiency scores), and gain the flexibility to expand the capacity of high-performing, sought-after schools so they had room for more children, the expansion of public school choice might lead to higher-performing, and more diverse, schools over time.

Of course, there may be differences between the nation’s capital and other cities. As more school districts expand choice and create unified enrollment systems, we’ll have a clearer picture of which systems give parents equal access to better schools.