KIPP Jacksonville became Florida’s first successful attempt to lure a nationally recognized charter school organization thanks, in large part, to local benefactors.

Jacksonville Greyhound Racing donated a dog track, and the charter organization gradually converted the clubhouse into classrooms. Wealthy board members helped fund the renovation, and today they’re financing a second building at far below the market rate. The small collection of schools enrolls close to 1,000 students and is still growing, adding as many as 200 a year. It has 1,400 children on its waiting list.

But the largess of its wealthy donors is running thin. And it’s out of dog tracks to renovate.

On Wednesday, Tom Majdanics, KIPP Jacksonville’s executive director, told state lawmakers he hopes the national charter school organization can bring “sibling” schools to more Florida cities. For that to happen, they’ll need to address the barrier his schools already butt up against: A shortage of funding for charter school facilities.

While lawmakers have increased funding for public schools in recent years, Florida remains ranked near the bottom for per-student spending. Combine that with eroding facilities funds, and the state may start to look inhospitable to national charter school organizations with a reputation for getting results in underserved communities. State officials have long sought to attract more of them.

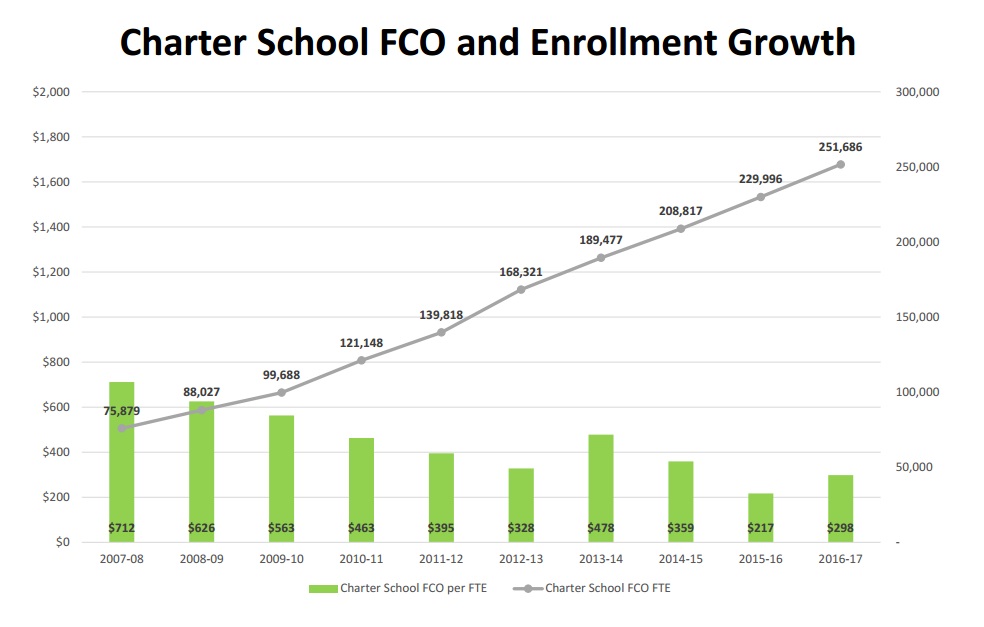

This graph, prepared for Wednesday’s Senate Education Appropriations Subcommittee meeting by the state Department of Education, illustrates what Majdanics described as a key problem.

Charter schools rely on an annual appropriations from the state Legislature. That funding has fluctuated between $50 million and $100 million in recent years. But Florida’s charter schools enroll more students each year. That means the same pool of money is being spread across more students and schools. Majdanics told the panel that the roughly $300 per student KIPP Jacksonville receives from the state “barely covers the interest on our loans” for capital expenses.

“When we bring in a new kindergarten class, we’re making a promise to be with those kids the whole way through,” he said in an interview. That raises a question: “Do we have a financial model, and a consistent core of public funding, to make promises to children that last beyond political cycles?”

Sen. David Simmons, R-Altamonte Springs, chairs the panel that invited Majdanics, as well as other charter school representatives and district superintendents from around the state. He’s filed a pair of bills that would increase the taxing authority of school districts and steer an even per-student share of facilities funding to charters.

The proposal would create a stable funding stream for charters. And it would at bring their funding more in line with what districts receive.

Right now, Florida’s school districts bring in close to $1,500 per student for facilities, on average. But the real numbers vary widely, from coastal communities where property taxes bring in thousands of dollars per student to rural areas that barely raise more than charters receive from the state.

Sumter County has one of the highest charter enrollment rates in the state — close to one in three of its public school students, thanks to the massive charter school in The Villages. And the district is one of a handful around the state that share its local facilities funding with charters.

Richard Shirley, Sumter’s school superintendent, said lawmakers should give districts discretion to raise property taxes to meet their varying needs. But because of the state’s diversity, he said hey should be wary of statewide mandates on how districts share the money.

Some lawmakers had concerns about charters that lease buildings from landlords tied to their management companies. Sen. Doug Broxson, R-Gulf Breeze, recently saw a charter school scandal erupt in his district. A charter school operator and three related companies have been indicted for money laundering and fraud. If the state is going to invest more money in charter school facilities, Broxson said, it should have some assurance that taxpayer-funded buildings will return to public control if the schools ever close.

In other words, long-sought changes to charter school funding are in the works. But there are details left to work out, and it’s not yet clear what form, exactly, they’ll take.

Richard Corcoran, the new House Speaker, has bemoaned the fact that Jacksonville is the only Florida city where KIPP has said up shop. He’s said cities shouldn’t have to depend on massive philanthropic efforts to bring similar schools to high-needs areas, and hinted at funding changes that would reward schools that extend their school days to help struggling students catch up academically.

[…] SCHOOLS: Officials say limited state funding is keeping more nationally recognized charter schools from opening in Florida, Redefined […]