Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Graduate training in the social sciences teaches students to think in terms of a multi-variable world. Humans naturally gravitate toward simple explanations of reality, such as X caused Y, when in fact isolating the impact of X on Y with reliability is very difficult.

Random assignment studies are the most useful in this regard, but these sorts of studies are difficult and expensive to arrange, and many policies do not lend themselves to random assignment. Many times, we have little choice but to make decisions based upon lesser evidence.

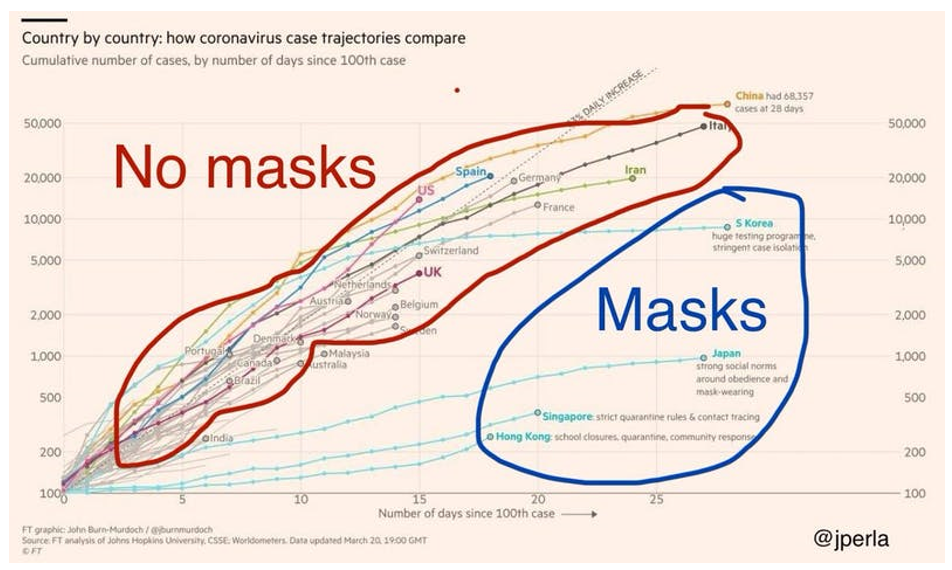

The social scientist is trained to look at technology leader Joseph Perla’s chart above and say, “We shouldn’t assume that South Korea, Japan and Singapore are having a good pandemic because of masks. It could be something else, or it could be multiple other factors. Masks could actually be bad.”

This is all potentially true. Moreover, unless you are willing to randomly assign people to wear masks in public and prevent the control group from wearing them, you cannot know for sure.

Policymakers, on the other hand, do not have the luxury of epistemological nihilism. They must make decisions, almost always based upon incomplete or otherwise imperfect information.

President Harry Truman once said: “Give me a one-handed economist. All my economists say, ‘on hand…’, then ‘but on the other … ’”

So, while the social scientist looks at this chart and suspects foul play, the pragmatist looks at it and says, “Well, there could be other things going on, and masks could still be playing a positive role.”

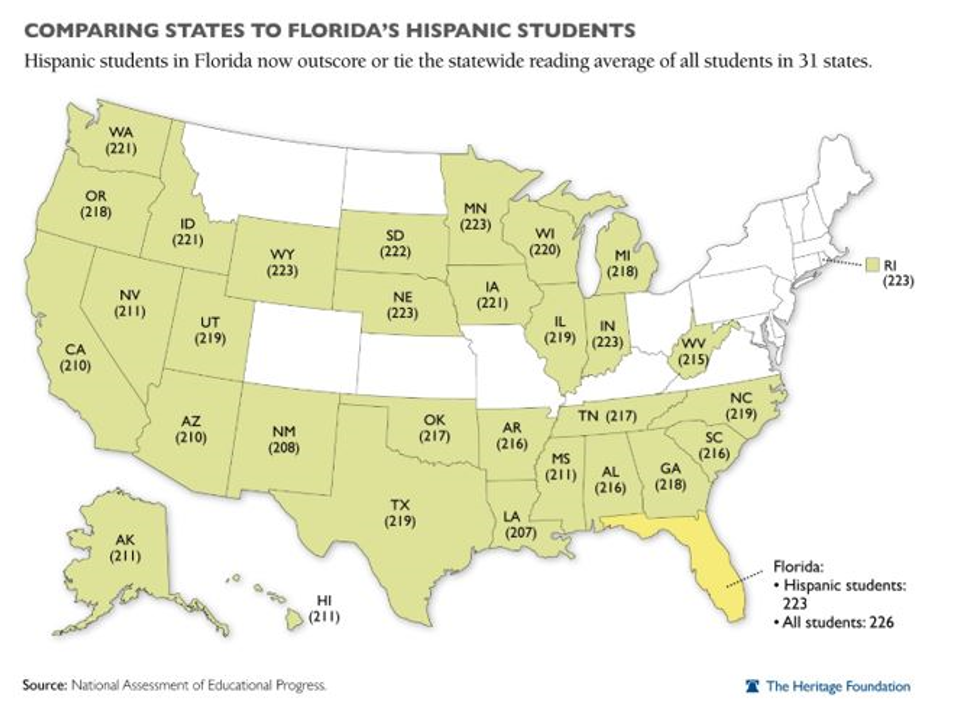

K-12 policy also gets made in a chaotic world with multiple policy changes occurring at the same time. Back when I collaborated with the Heritage Foundation to produce the map below comparing the fourth-grade NAEP scores of Hispanic students in Florida to the statewide averages for students across the country, critics raised the social science objection: “You don’t know which Florida policy led to the increase,” was the essence of the complaint.

This was entirely correct from the point of view of the social scientist, but the pragmatist in me required me to say: “Since we don’t know which of the many reforms in the Florida cocktail led to the improvement, don’t take any chances – implement all of them.”

Likewise, someone might want to study everything Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore have done to prevent the spread of COVID-19. It is not necessarily the same approach. But right about now, encouraging people to wear masks in public is looking like a pretty good idea, not dissimilar from studying a state whose minority students score a grade level higher than your statewide average on reading.