The latest report on academic performance in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program devotes historic attention to evaluating the students who enter and, later, leave. This is the first time this subset has been thoughtfully and empirically analyzed to determine who these students are, why they leave and how they perform once they return to public schools. The researcher’s findings lend credible support to common sense: students who struggle seek other options.

The latest report on academic performance in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program devotes historic attention to evaluating the students who enter and, later, leave. This is the first time this subset has been thoughtfully and empirically analyzed to determine who these students are, why they leave and how they perform once they return to public schools. The researcher’s findings lend credible support to common sense: students who struggle seek other options.

The reasons that students transfer schools and how they perform can be overstated by supporters and opponents of the scholarship program alike. It is important to clarify the contradictory claims in this debate as more than 60,000 students enter the scholarship program this fall. The report, written under contract with the state by respected Northwestern University researcher David Figlio, faults neither the public schools nor the private schools, and simply asserts that students seek new schools because their prior option didn’t work for them.

For example, Figlio reports that for six consecutive years the students entering the scholarship program “tend to be the lowest performing students in their prior (public) school” and this is a “trend that is growing stronger over time.” This is not to say the public schools as an institution are failing low-income students, but more likely that the particular public school didn’t meet the unique learning needs of the child who chose the scholarship. Parents are seeing their child struggle and they are using scholarships to pursue new options.

The same could also be true for students who return to public schools.

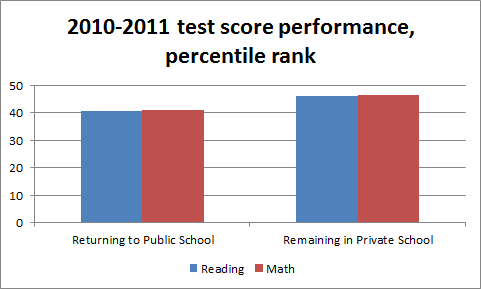

Figlio found that students who returned to the public schools, despite being eligible to keep their scholarship, ranked 5.4 percentile points lower in reading and math than the students who remained in the scholarship program.

This statistically significant correlation weighs heavily in favor of the simple answer: It is likely that these students are transferring back to a public school because their particular private school didn’t work out for them.

This simple proposition begs an important question, though: Are these struggling students falling further behind while they are in the scholarship program? Figlio concludes they are not.

To be sure, scholarship students who return to a public school score lower on the FCAT than other low-income students who remained in public school. For 2011-12, the average low-income public school student who never entered the scholarship program ranked in the 41.2 percentile in reading and 42.9 percentile in math on the FCAT. For 2011-12, the average low-income scholarship student who returned to a public school was in the 30.8 percentile in reading and the 26.3 percentile in math.

But that gap is misleading for at least three reasons:

1) It does not take into account that the scholarship students were struggling in a public school before they chose a private option. Overall, in the year prior to entering the scholarship program, these students averaged in the 33.2 percentile in FCAT reading and 33.9 percentile in FCAT math.

2) It includes a first-year performance dip that is typically seen in any transitional year for students. Figlio examined the change in FCAT scores of all low-income public school students who transfer from one school to another outside the normal progression and found a dip of two percentile points. Accordingly, the FCAT scores for returning scholarship schools appear to increase by at least that amount in the second year and beyond.

3) These students’ prior public-school FCAT scores were also three points lower than those of the newest scholarship students who had taken the FCAT for 2010-11. In other words, the scholarship students who returned to a public school performed worse in years prior to entering a private scholarship school than did their peers who never entered the program at all and their peers who just entered the program.

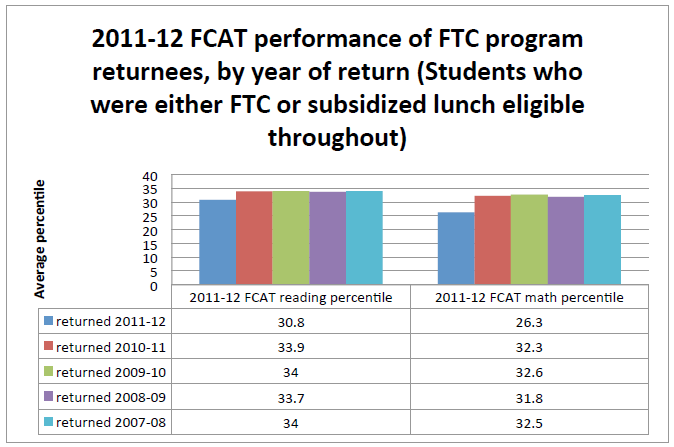

The other painful reality is that these students who return to public schools with lower test scores don’t improve over time in their new environment. For example, students who returned to public schools in 2007-08 score no differently in reading (34th percentile) or math (32.5th percentile) on the 2011-12 FCAT than students who returned to public schools four years later (33.9th percentile and 32.3rd percentile respectively).

The other painful reality is that these students who return to public schools with lower test scores don’t improve over time in their new environment. For example, students who returned to public schools in 2007-08 score no differently in reading (34th percentile) or math (32.5th percentile) on the 2011-12 FCAT than students who returned to public schools four years later (33.9th percentile and 32.3rd percentile respectively).

Returning students struggled before they entered the private school, while they attended the private school and they continued to struggle upon returning to public school. Figlio concludes that the scholarship program “appears to have neither advantaged nor disadvantaged the program participants who ultimately return to the public sector.” This subset of scholarship students shows persistent difficulty in education regardless of whether that education occurs in public or private school.

Figlio calls them “particularly struggling students,” and they do seem to be the most disadvantaged of disadvantaged students. This important research examines the impact of students migrating in and out of the nations largest school choice program for low-income students. The evidence presented suggests that parents are not making frivolous decisions on where their child should be educated but are, in all likelihood, making measured choices against the backdrop of their child’s history of struggling school performance.

It would be great to see similar data on the Florida McKay Scholarship for Students with Disabilities. I imagine that the results would conceptually be similar, i.e., those who struggle in school continue to seek options and to struggle whether in private or public school.

That is a great idea and I bet you’re right.