Jane Strawbridge drives 100 miles a day during the week so her granddaughter, Jaime, can attend a Central Florida charter school that serves children with learning disabilities.

It’s a huge commitment, but worth the extra effort when Strawbridge considers how Jaime struggled in a traditional district school with few resources for special needs students.

“She was teased and bullied because she wasn’t able to process information as quickly as her classmates,’’ Strawbridge said. “She hated school every day.’’

“She was teased and bullied because she wasn’t able to process information as quickly as her classmates,’’ Strawbridge said. “She hated school every day.’’

After five disappointing years, the family finally discovered Pepin Academies, a Tampa Bay area nonprofit charter school that specializes in students with specific learning issues such as language impairment and autism. In August, Jaime started fifth grade at Pepin’s satellite campus in Riverview, just east of Tampa. There, she’s among 121 students in grades 3-7.

“She’s so happy,’’ Strawbridge said. “She looks forward to getting up in the morning.’’

Charter schools often are criticized for cherry-picking students, even turning away the most disadvantaged ones. But at Pepin Academies, “we purposely take the low-performing kids,’’ said Carolyn Scott, director of academics. “We purposely take the ones struggling.’’

A study of enrollment rates among special education students shows a gap nationally between charters and traditional public schools. And while that may be reason for concern, there also might be other factors at play beyond charters denying access.

A new report that looked at the disparity in New York schools found that in many cases, parents of students with disabilities simply aren’t choosing charter schools. Some may be satisfied with their current schools, or may feel charter schools aren’t equipped to serve their child’s special needs.

As the charter movement continues to grow, a new nonprofit hopes to ensure kids with disabilities have the same access to charter schools as their peers. Among its goals, the National Center for Special Education in Charter Schools plans to identify barriers for special needs students and create coalitions to help protect students’ rights while upholding the mission of charter schools – to provide choice.

Charters offer an ideal environment for children with special needs, said Scott, a former district ESE teacher and youth specialist for the juvenile justice system. Because the schools have more freedom, they can focus on those needs in ways traditional public schools just can’t.

For Pepin, that means pouring resources into providing additional aides, speech and physical therapists, counselors, a multi-sensory lab – things district schools, which must serve all types of students, sometimes don’t have the luxury of doing.

“We can’t be everything to everybody,’’ Scott said. “The district has to be.’’

Pepin was founded in 1999 by parents of children with special needs. It’s the only K-12 public school in Florida for students with learning disabilities that offers a standard high school diploma as well as a special diploma. Of graduates, 80 percent receive the standard diploma, Scott said.

Pepin’s main campus sits on 10 acres in Tampa and serves 505 students. Some are in the K-12 program. Others ages 18-22 participate in a two-year “transition” program, gaining life and employment skills at 11 job training sites that include the Tampa Police Department and the local public defender’s office.

“We look at the whole child,’’ Scott said. “That’s what makes us different.’’

And that’s what hooked Strawbridge. She found out about Pepin Academies a few weeks before school started, when another Tampa charter school that didn’t have an opening made the suggestion. Once Strawbridge talked with Pepin administrators, she signed up without thinking twice about the commute.

Her only thought, she said, was what doors might open now for Jaime, a smart, artistic girl who still bears the scars of being bullied. “This is going to affect her the rest of her life,” she said. “If they get left behind at this age, it’s just hard to catch up.’’

Next year, Pepin administrators plan to open a third campus in nearby Pasco County, to accommodate 25 families making the daily trek to the Tampa-area campuses. For now, Jaime is content at the Riverview school, which plans to add grades eight through 12 in coming years.

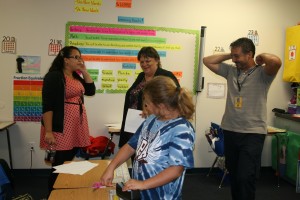

It’s located inside a bright yellow storefront that sits beside a day care along winding neighborhood road. Inside the narrow building, classes are kept small with 12 students to one teacher and an aide. There’s an on-site speech pathologist, physical and occupational therapy, and a guidance counselor that’s also a licensed mental health counselor – like Scott.

There’s also art, music and P.E. Students can play sports and attend dances – all the things that allow them to have a typical school experience.

On a recent visit to Andrea Kennedy’s science class, third- and fourth-graders sat rapt while learning about African animals. A former private school teacher, Kennedy joined Pepin Academies this year, bringing her youngest daughter, who has a language delay, with her.

“This is a much better fit for her,’’ she said. The move also fulfills a dream, she said, noting that at her old school, “the kids I saw struggling in my class always stole my heart. I always wanted to help them.’’

Her aide, 24-year-old Tessa Rodrigues, graduated from Pepin Academies’ Tampa campus in 2007. She remembers how self-conscious she was about her learning disability in math. Pepin gave her the confidence to move forward, she said. Now she plans to attend community college and possibly pursue a career in education.

And her eye’s on Pepin.

“I want to help these kids where I was helped so much,’’ Rodrigues said.