In 1998, at a luncheon in Chicago, former superintendent, activist and now-icon Howard Fuller was on an education panel with an up-and-coming state senator. Barack Obama told the audience that vouchers were a “distraction,” and said those who support them don’t want to tackle the difficulties of changing the “entire system.”

In 1998, at a luncheon in Chicago, former superintendent, activist and now-icon Howard Fuller was on an education panel with an up-and-coming state senator. Barack Obama told the audience that vouchers were a “distraction,” and said those who support them don’t want to tackle the difficulties of changing the “entire system.”

Fuller laments the spectacle of black leaders going toe to toe in public, but he did not shy from a retort. As he recalls in his just-released autobiography, “No Struggle, No Progress,” he answered from experience about teachers unions’ resistance to change, then lowered the boom:

“And you sit here and claim that we can make changes in the existing system? If you can do that, God bless you. But I’m going to tell you this. Those of us who are out there fighting are not going to wait for you to do that. We’re going to keep trying to find ways to help people whose kids are being undereducated, miseducated, not educated.”

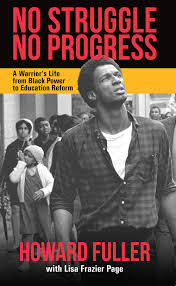

Howard Fuller’s passion for parental choice is common knowledge in choice circles. He is arguably the best known and most revered figure in that realm. But thanks to his book, a wider swath of people will get a chance to meet him. Written with noted author Lisa Frazier Page, the book would compel even if school choice wasn’t such a hot topic; it chronicles an extraordinary American life. But it has the potential, too, of knocking a few more holes into the tired narratives about choice supporters and what motivates them.

Low-income parents are lining up in droves for alternatives to district schools, and one prominent Democrat after another is swinging towards them, including President Obama who, while still hung up on vouchers, wholeheartedly supports charter schools. The Dem divide is real, and as it grows, more rank-and-file Democrats will have second thoughts. Fuller’s story can hasten the process. Politically, he’s part of the same extended tribe, and for many folks that external validation makes all the difference.

It wasn’t until after he embraced vouchers in the late 1980s, Fuller notes, that he heard of economist Milton Friedman. Fuller’s views about education and everything else were forged in a different world: through his own humble upbringing by strong black women who found ways to get him the best education possible (including stints in Catholic schools); and in the tumult of the 1960s – in civil rights and Black Power, in protest marches and rent strikes.

It’s clear from every page that Fuller is motivated by love for “my people,” and for finding ways to right wrongs and uplift them. “No Struggle, No Progress” is brimming with passages that speak to his heart – passages like this one, where Fuller describes one of the Durham, N.C. neighborhoods he was assigned to help as a community organizer in the 1960s:

“Though I’d grown up in public housing and spent my earliest days in a poor southern community, I’d never seen poverty and neglect like this. Hayti, the largest neighborhood in my target area, sat in the heart of a major city, yet some areas still had dirt streets. Dirt streets! In the middle of town! That was incomprehensible to me. Shotgun shacks were everywhere, and some of them had no running water indoors. My heart hurt when I saw how my people were living and how they had accommodated themselves to survive under conditions that no human being should have to endure. Anger burned deep inside. But far from feeling overwhelmed, it made me even more determined to figure out how to change the condition.”

Early on, Fuller was captivated by another concept too: “maximum feasible participation.”

That’s the notion, he writes, “that poor Black people, who had long been dictated to even by well-meaning whites, should play a major role in determining what they needed and how they should get it.” As the book makes clear, that thread in his worldview has never frayed.

Fuller fought too many battles to list. But he rarely fought from a desk.

At his first protest demonstration – over school de-segregation in Cleveland, in 1964 – police dragged him down three flights of stairs. In North Carolina, his organizing of poor communities was so effective, the governor denounced him and the cops put a bounty on his head. In his first foray into school choice, he founded Malcolm X Liberation University, a short-lived but inspired institution where he was, officially and irreverently, the H.N.I.C. After he embraced Pan-Africanism, he spent a few weeks with guerillas in Mozambique, eating lizard meat, watching government helicopters chase rebels through banana plantations and wishing he brought something better for his feet than dress shoes.

In the mid-1970s, Fuller briefly drifted into a radical fringe. But when it descended into madness (the passages about the Revolutionary Workers League are particularly surreal), he made a quick exit. And then, amazingly, he transitioned, values intact, to insider.

In Wisconsin in the early 1980s, the governor appointed Fuller to lead the Department of Employment Relations, where he championed affirmative action and fought Reagan-era efforts to dismantle it. As Milwaukee’s superintendent in the 1990s, he fought as hard as anyone to beef up school funding.

It seems bizarre to have to say this, but given the caricatures that somehow persist it feels necessary: This is not the resume of somebody who embraces vouchers and charter schools to help scheming corporations profit off of poor kids.

“No Struggle, No Progress” touches only briefly on some of the thorny debates that ripple through parental choice – like whether vouchers should be universal or limited to the poor (Fuller supports the latter, but is open to a sliding-scale system) or whether poor performing but still popular voucher schools should face regulatory interventions (Fuller says yes). The book also doesn’t note explicitly that despite perception, progressives have a rich tradition of embracing choice (see: Coons, John E., and Moynihan, Daniel Patrick), and that history is rife with examples of black Americans doing so out of necessity, be it freed slaves who built schools because they were tired of waiting for the government to do it, or civil rights activists in Mississippi and elsewhere creating Freedom Schools.

But it seems ungrateful to even bring that up. Any quibble about this or that being left out is more than mitigated by the details of Fuller’s incredible life. I have no doubt that many people, like me, who have admired Fuller from afar will be unable to put the book down. My hope is that others will pick it up. We can all learn from Dr. Fuller’s take on struggle and progress.

[…] AMERICANS: A new book tells life stories from Howard Fuller, a progressive black leader who has championed school vouchers for decades and even gone toe-to-toe with President Barack Obama about […]

School choice is just a way to do two things.

First, it is a way to divert funds to private businesses. The way this is done is unconstitutional in most states, though politically biased courts allow it to continue.

Second, and much worse, it is working very effectively to re-segregate our schools. Is that really the direction we want to go?