The first-ever state supreme court ruling finding charter schools unconstitutional continues to stir debate all over the country, and has inspired some choice opponents to raise questions about other charter school laws, including the nation’s oldest.

While there is little reason to think the Washington State Supreme Court’s legal reasoning could spread to many other states, it is the latest illustration of how an idealized past that never was continues to create barriers to a 21st-Century education system.

Opponents try to cast a romantic vision of free, universal public education as a foil against school choice, relying on a mythical conception of “common schools” that has rarely squared with reality.

Getting American common schools to serve all students required more than a century of political turmoil, countless lawsuits and no shortage of attempts — from Dust Bowl-era California farm towns to the Freedom Schools launched by the Civil Rights Movement — to create separate educational opportunities for religious and ethnic minorities who were excluded from, or under-served by, traditional public school systems.

In many ways, the fight for inclusion and equity continue to this day.

“[P]eople too frequently forget that those schools were at different times not open to blacks, religious minorities, or, until the 1970s, students with special needs and disabilities,” Andrew Rotherham and Richard Whitmire wrote in a recent piece for The 74.

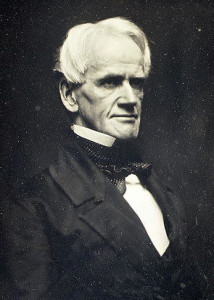

Common schools were first popularized in the mid-1830s by Massachusetts education reformer Horace Mann. The idea spread through out the U.S. over the next few decades during a time when anxiety over waves of immigrants, many of them from Ireland and other predominately Catholic countries.

In Massachusetts, Mann used his power over public funding of education textbooks to push religious uniformity. According to Harvard professor Paul Peterson, “state-approved textbooks were limited to those that praised the God of Creation, not the God of Judgement.” The aim was to “free schoolchildren both from the orthodox Protestant doctrine and from the harsh Catholic beliefs that immigrants were bringing into the Commonwealth.”

In his book Myth of the Common School, Boston University professor Charles Glenn wrote that Mann “saw the function of the common school as prevention not only of the breakdown of morality but also of the excesses of religious enthusiasm.”

Private and parochial schools were antithetical to Mann’s common-school ideal. They allowed diverse religious sects to “maintain separate schools, in which children are taught, from their tenderest years, to wield the sword of polemics with fatal dexterity,” he wrote in the Common School Journal in 1839.

In this view, “nonpublic schools were a direct threat to the reform program of social progress and unity through a universal and uniform popular education,” Glenn wrote. To Mann, a one-size-fits all school system was a remedy to conflict.

Yet Mann’s common school concept remains a source of conflict today. The ethical and moral lessons of students in a one-size-fits all environment have created a battleground in the American culture wars, from book banning, to the fight against communism in the 1950s, to the fights over textbooks and the Common Core standards.

The modern school choice movement offers a different way to resolve at least some of these conflicts, which is in keeping with our country’s ideals. It allows us to recognize there isn’t one right way to educate children, and that educational options should match the diversity of our country’s students.

Mann’s lasting contribution was advancing the idea that all children should be educated. In this way, he helped give rise to America’s public-school system, which Adlai Stevenson once called “the most American thing about America.”

But the old ideal of the common school often excluded immigrants, racial minorities, and religious sects that weren’t Protestant. It has unfortunately been codified in Blaine Amendments and other constitutional barriers to an educational system that embraces the principles common school advocates all too often ignored, like pluralism and diversity.

Over time, the conception of common schools has expanded from primary school to include kindergartens, high schools, IB programs, magnet schools, vocational programs, and a range of other options. That evolution should continue.

Nice piece Patrick…thanks.