Its champion gone, ambitious plan for school choice in California fizzles

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and the last part of a serial about a proposed voucher initiative in late ‘70s California. In Part III, libertarian choice supporters reject a ballot proposal pitched by Berkeley law professors, and offer their own.

The professors wanted Milton Friedman’s blessing. So did the libertarians.

Calling Friedman was the “first and natural thing to do,” Berkeley law Professor Jack Coons recalled in an interview. The two had known each other since the early 1960s, when both lived in Chicago. Coons hosted a radio show; Friedman was a frequent guest.

As luck would have it, Friedman was now based at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, in nearby Palo Alto. He and Coons and their wives occasionally met for dinner.

Initially, Friedman was excited and encouraging about the ballot initiative, Coons said. Then he wasn’t.

The regulations spooked him, Coons said. Friedman never told him directly. But he heard as much from potential donors to the initiative campaign, and it wouldn’t have been surprising. Friedman’s biggest fear about school choice was government intrusion.

According to Coons, donors told him Friedman had been in contact with them and said the plan was wrong-headed. He convinced them to hold off on contributions, and to wait for better school choice proposals down the road.

***

The libertarians had better luck.

Activist Jack Hickey said he sent Friedman a copy of his “performance voucher” proposal, and talked to him by phone. He said Friedman liked it enough to give it a positive review in writing. As proof, he produced a letter from Friedman on Hoover Institution letter head.

Friedman wrote that he liked how the performance voucher would curb government’s role in education, but was bothered by heavy reliance on standardized testing. He concluded, though, that “any one of the three approaches (an unrestricted voucher, your approach, or an appropriately designed tax credit) would be vastly superior to our present system.”

Both David Friedman, Milton Friedman’s son, and Robert Enlow, president of the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, said the letter appears to be authentic.

***

For some, two competing choice proposals weren’t enough. In the summer of 1979, petitions began circulating for a third.

The educational tax credits promoted by the libertarian-minded National Taxpayers Union would give California taxpayers a state income tax credit of up to $1,200 per student for educational expenses, including private school tuition. Public school parents could also use the tax credits, for things like field trips and lab fees.

The NTU was allied with the forces that spearheaded Prop 13, and the group’s West Coast director characterized the choice proposal as an extension of the tax revolt. He told a reporter the group came close to supporting Coons-Sugarman, but ultimately decided against it because “it didn’t leave the private schools free from control.”

Jack Dean, a longtime libertarian activist who worked on the NTU effort, said in an interview that the professors’ plan gave libertarians heartburn. “The tuition tax credit was kind of the antidote,” he said.

Milton Friedman praised the NTU proposal too, saying in a letter to Dean, “Its effect would be essentially identical with the kind of unrestricted voucher plan I have been supporting and promoting for decades.”

Dean said his recollection is NTU spawned the proposal, then asked Friedman for support. He said the group didn’t raise much money from major donors, but Friedman’s endorsement helped.

***

Now the professors were under fire on two fronts. And yet, as summer unfurled, their plan continued to roll.

In August, supporters mailed out 200,000 petitions, prompting these words in the Los Angeles Times:

Public education groups, which are bitterly opposed to the voucher plan and vow to fight its passage, have been watching fearfully for nearly a year as the initiative effort took shape.

Now, the potential threat has become a reality with the official start of the petition campaign.

The consensus is that the voucher plan, called Family Choice in Education, stands an excellent chance of winning voter approval – if the initiative qualifies for the ballot.

The story noted Coons and Sugarman seemed to have overcome initial hurdles.

They had hoped to get a voucher bill introduced in the state legislature in the spring, to generate publicity, but no lawmaker was willing to “face the wrath of education groups, including powerful teacher unions.” They also didn’t have immediate luck finding a campaign consultant, but eventually hired a veteran known for his work for “liberal candidates and causes.”

The consultant had previously worked on the campaign for the state superintendent of public instruction. He boldly told the newspaper his goal was a million signatures, with 800,000 by the end of November.

***

The coverage missed what was happening behind the scenes:

The liberals were floundering.

As if to underscore the point, The Sacramento Bee reported in September that the education establishment had decided on a new strategy for the initiative: Ignore it.

California’s educational establishment has decided not to launch a full-fledged campaign – for the time being – against the proposed school voucher initiative, a strategy designed to give the controversial measure as little publicity as possible …

Coons and Sugarman had no experience with political campaigns, and it was beginning to show. Lack of money and organization was becoming a major issue. And private schools were getting edgy. They told newspapers the regulations in the plan were too much.

By mid-October, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which should have been a steadfast ally, still hadn’t determined whether it would support the initiative.

The deadline for 553,790 signatures was just 10 weeks away.

More than ever, the campaign was missing the man who had spurred it on and agreed to lead it.

***

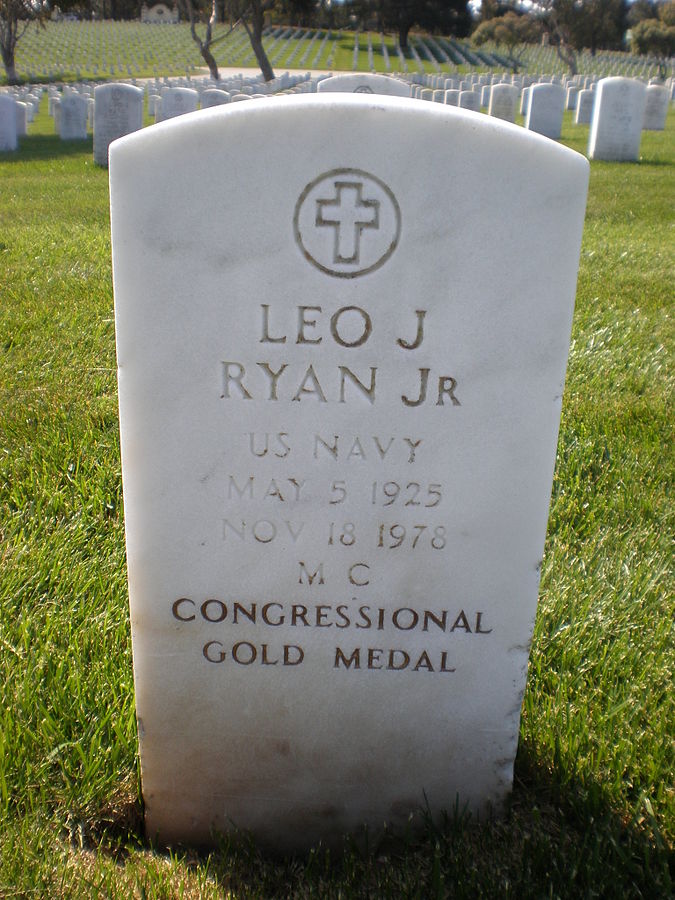

Congressman Leo Ryan never returned from Jonestown. He was murdered on Nov. 18, 1978.

Jim Jones’ thugs shot him at the airport. Four others in his entourage were killed; nine were wounded. Later that day, Jones ordered more than 900 temple members to drink cyanide-laced Flavor Aid.

Only two months after his introduction to Ryan, Coons felt the same shock as the rest of the planet, and tremendous sadness for Ryan and his family. At the same time, he knew the ballot initiative had been rocked, too.

Coons and Sugarman did their best to soldier on. For a year after Ryan’s death, their efforts to make their vision of school choice the law of the land in California got serious play.

But the truth is, its odds for success all but died when Ryan did.

***

The Berkeley professors failed to get enough signatures. The two competing efforts also fell short.

Coons called it quits on Christmas Day, 1979.

“It will be tried again,” he told a reporter that day. “When is the question.”

The End

Epilogue

Only one person besides Jack Coons knows the extent to which Ryan was involved with the California voucher initiative: U.S. Congresswoman Jackie Speier.

Speier, Ryan’s aide in 1978, accompanied the representative to Guyana. She was shot five times and left for dead. Elected to Congress in 2008, she represents much of the same stretch of the San Francisco Bay area that Ryan did.

The other Ryan aide who met with Coons, G.W. “Joe” Holsinger, died in 2004.

Ten weeks after redefinED contacted Speier’s office, her press secretary said the congresswoman was too busy to talk about the ballot effort.

Speier is a Democrat who has been endorsed and financially backed by teacher unions. But she has played little role in shaping education policy, either in Congress or during an earlier stint in the California State Assembly. In 2000, she opposed a conservative-led ballot initiative to create a statewide voucher program in California (so did Coons), but her opposition to school choice has never been particularly public or strident.

Many others who may have had insight into what happened in 1978 and 1979 are either gone, or won’t talk, or can’t be reached. Among them:

Congressman Ryan’s daughter Pat, a former executive with the California Healthcare Association, did not return calls. Former Los Angeles Times reporter Jack McCurdy, who covered the ballot effort more than any other journalist, couldn’t be reached.

Wilson Riles, the state superintendent at the time of the ballot effort, died in 1999. Ralph Flynn, executive director of the California teachers union at the time, died in 1995. Raoul Teilhet, the union president, died in 2013. Al Shanker died in 1997.

Henry Lucas, a black dentist in San Francisco who was described in news stories as an advocate for the ballot measure, died in 2009. Another visible supporter, Berkeley Law Professor Leonard Ross, died in 1985. The campaign consultant, Sanford Weiner, died in 1991.

Michael Kirst, president of the California State Board of Education from 1977 to 1981, was reappointed in 2011 by Gov. Jerry Brown and is again president. He said in an interview he was not aware of Ryan’s interest in the Coons-Sugarman plan, but said it wouldn’t have mattered. Voters would have never taken a “plunge into the unknown,” he said.

Carol Ruth Silver, a former Freedom Rider and former member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, was part of a Northern California contingent promoting the ballot initiative. She said in an interview she can’t recall details. But she looks back on the initiative as politically progressive and “the first disruptive idea to come out of Northern California.”

Nothing like Coons-Sugarman has been tried since, in California or beyond.

Since 1980, nine voucher or voucher-like proposals have made it on to state ballots, including in California in 1993 and 2000. None included the regulations Coons and Sugarman thought necessary to help low-income and working-class families. All lost by wide margins.

Full disclosure: The author is employed by Step Up For Students, a nonprofit which hosts this blog and helps administer two educational choice programs: Florida’s tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in America, and Florida’s Personal Learning Scholarship Accounts program, its education savings account for students with special needs.