On the California school choice front, an unexpected champion

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and Part II of a serial about a voucher ballot initiative in late ‘70s California. In Part I, law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman find a surprise supporter in U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan.

The Berkeley professors had found a powerful ally.

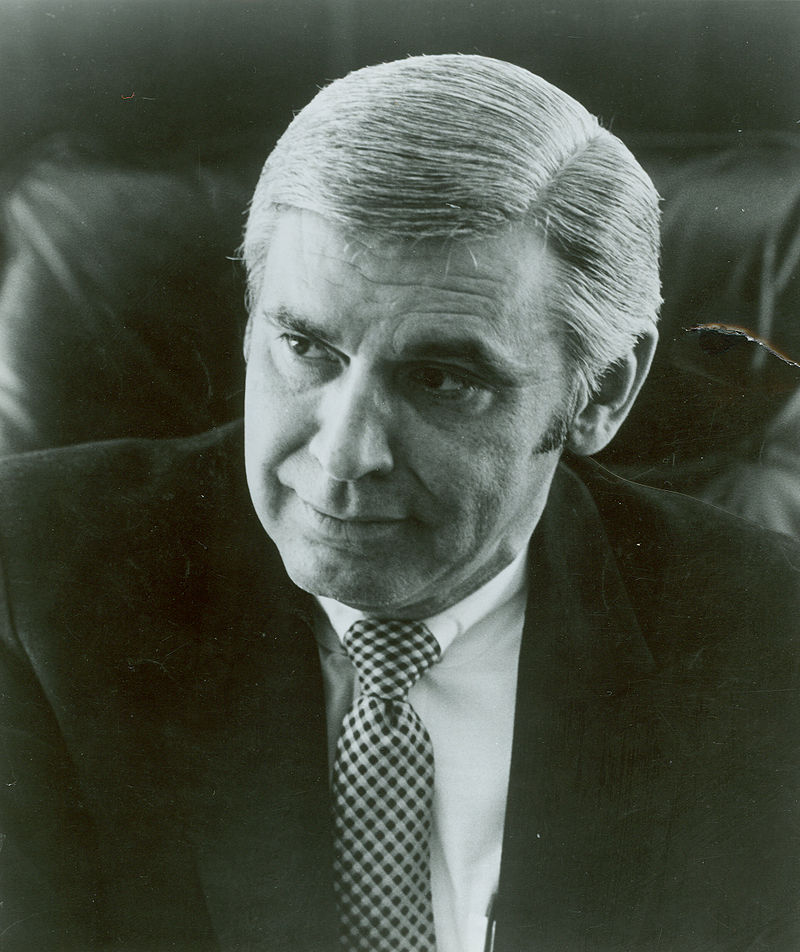

Congressman Leo Ryan was popular and fearless, a liberal with a maverick streak, a square peg with a common touch. It’s a safe bet he was the only member of Congress with a master’s in Elizabethan literature. And importantly for a ballot initiative that sought to make school choice the law of the land, he had been a teacher in California public schools.

Ryan also had a knack for making headlines.

Before election to Congress in 1972, he served nine years in the state assembly, where he became famous for exploring the nitty gritty behind the news. One newspaper called it “investigative politics.”

After riots in Los Angeles, Ryan worked as a substitute teacher in the Watts neighborhood. A few years later, he went undercover to experience death row at Folsom Prison. As a congressman, he visited Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, at one point laying down on the ice between a hunter and a seal pup.

As fate would have it, Ryan was also a voucher guy.

Years later, Jackie Speier, his former aide, would point to his support for school choice as a prime example of his political independence. Ryan “seemed unlike other politicians,” Speier said. “He was provocative; he didn’t mince words or beat round the bush; he told you what was on his mind whether you wanted to hear it or not; and he took pride in not being able to be pigeonholed into any one ideology.”

Ryan may have been willing to buck his party on vouchers. But it’s also true it wasn’t as odd for Democrats in the 1970s to back public support for private schools.

In 1977, Democratic U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan introduced a bill for tuition tax credits that drew 50 co-sponsors – 26 of them Republicans and 24 of them Democrats. At that time, the previous three Democratic candidates for president, Hubert Humphrey, Eugene McGovern and Jimmy Carter, had backed similar proposals on the campaign trail.

According to Coons, Ryan was all in on the voucher initiative.

After their last meeting, he said Ryan told him: “You guys are going to polish this up as best you can, and we’ll get ready to announce it and start pushing it through the process just as soon as I get back.”

The congressman was headed to South America.

***

As word spread, panic mushroomed.

The Los Angeles Times predicted the voucher initiative would be “the biggest and most bitter fight over schools in many years.” State Superintendent Wilson Riles predicted “chaos.” The executive secretary of the powerful California Teachers Association, Ralph Flynn, said his group would defeat the proposal “whatever the cost.”

Even Al Shanker, the legendary leader of the American Federation of Teachers, weighed in, saying the California proposal could produce “the fight of the century.”

By early 1979, Riles was urgently contacting supporters, mobilizing for a statewide campaign.

If this thing gets on the ballot, he told the San Jose Mercury News, “who knows what might happen.”

Game on.

***

Coons and Sugarman didn’t dream up their plan on a whim. They had been refining it for a decade.

The motivation was simple – to give parents, particularly poor parents, real power to determine the best education for their children. But the details were complex. Unless the new system was well designed and regulated, they believed, low-income children would continue to be denied a fair shake.

The professors envisioned three types of K-12 schools under a new banner of public education, all to be called “common schools.” There’d be:

- Traditional public schools.

- “Family choice schools” (private schools that agreed to participate in the choice program).

- And a new category, “independent public schools,” which closely resemble what are now called charter schools.

Parents could choose whatever common school they wanted, with public funding for family choice schools coming in the form of “educational certificates,” i.e. vouchers. But Coons and Sugarman veered from conservative and libertarian models in key ways.

Access: Under their plan, independent public schools and family choice private schools would be required to set enrollment limits at each grade level. Then they’d be required to accept every student who applied up to those limits, beyond those previously enrolled and given priority. If the number of applicants exceeded the number of open seats, there’d be a lottery.

Funding: The average scholarship amount would be 90 percent of total per-pupil spending for traditional public school students, but the Legislature could adjust the amount based on special needs, cost-of-living and other factors. It would also create a system of “supplementary scholarships” that allowed parents to apply for additional funding based on a sliding-scale for income. In other words, low-income parents could receive more state money, to make it easier for them to access higher-tuition schools.

Regulations: All three types of schools would be required to provide transportation with conditions set by law. None could discriminate based on race, religion or gender. The Legislature would establish uniform standards for discipline, create programs to fund capital costs and provide a public database with information about each school. It would also offer grants for parents to hire education advisors.

As for cost, the California Initiative for Family Choice proposed capping total public spending on elementary and secondary education at 1979-80 levels, with subsequent increases only for inflation and enrollment growth. It would nix property taxes as a source of school funding.

The professors also wanted to ensure the state couldn’t stall.

Within five years, the Legislature would have to devote enough resources to the establishment of independent public schools and private family choice schools that 30 percent of the state’s K-12 students could enroll in them.

By way of comparison: About 10 percent of Florida students are in private schools in 2015, even with the nation’s biggest tax credit scholarship program (established in 2001) and one of its biggest K-12 voucher programs (established in 1999). After 20 years in existence, Florida’s charter school sector, also among the nation’s biggest, accounts for 8 percent of K-12 enrollment.

Too much, too fast?

Coons had no qualms. He thought of the suffering America’s system of public education was inflicting on low-income families, particularly black families. If we can end it, he concluded, we should end it.

With Ryan, they had a chance.

***

The establishment wasn’t about to wilt.

The executive secretary of the state teachers union called the Coons-Sugarman plan “social dynamite” and said it would make public schools the dumping grounds for the poor. He said it would create a “permanently institutionalized drone class.”

The teachers union president in San Diego said vouchers would appeal to “all the racist antibusing fans” and open a Pandora’s box of extremism.

“We can have People’s Temple schools and the public will support them. We can have Nazi schools and Hare Krishna schools and devil’s arts and observing-the-wall schools,” he said. “And we can have a nation of little individual philosophies running around, and Hare Krishna and People’s Temple schools all going around zapping each other.”

Later in the year, at a legislative hearing on vouchers, another teachers union leader went even further, saying the school choice plan was “a cruel and vicious attempt at not only educational apartheid but also educational genocide.”

Opponents knew timing favored the insurgents.

This was just months after 62.6 percent of voters flipped off the government with Prop 13, the tax revolt that reverberated across America. This was years before today’s dominant narrative about school choice – right-wing plot to privatize public schools – had been set in stone. And these were liberals – Left Coast, Berkeley liberals, at least by perception – leading the vanguard.

In October 1978, a statewide poll showed 59 percent favoring vouchers.

From Chula Vista to Crescent City, school boards and teachers unions couldn’t believe what they were seeing: From an unexpected place, the unmistakable surge of a tidal wave.

They weren’t the only ones thinking the worst.

Stay tuned for Part III of “California Dreamin’ ” next week.

Full disclosure: The author is employed by Step Up For Students, a nonprofit which hosts this blog and helps administer two educational choice programs: Florida’s tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in America, and Florida’s Personal Learning Scholarship Accounts program, its education savings account for students with special needs.

“By early 1979, Riles was urgently contacting supporters, mobilizing for a statewide campaign.”

For more information, see:

https://pawmeister.com/PAbackground.htm

Also, John Coons and I were invited and appeared in Los Angeles before the Assembly Education Committee, Chaired by Assemblymember Leroy Greene.