Generations of black students fought to leave St. Louis public schools, but third-grader Edmond Lee wants to remain in his.

Under city rules designed to promote racial desegregation, however, he might be forced out of his school because he is black.

Edmond and his mother, LeShieka White, are moving to the suburbs, away from the public charter school he attends. While researching Edmond’s enrollment options, White discovered a 33-year-old desegregation agreement prohibits black students living in the suburbs from enrolling in inner-city public schools, and non-black students from leaving.

White, a victim of unintended consequences, has since gotten a good bit of media attention, and started a petition to change the state law to allow her son to stay in his school. It now has more than 120,000 signatures.

James Shuls, an assistant professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, argues the race-based transfer restrictions in his city may already be unconstitutional. He points out a similar program in Arkansas was struck down in 2012 after the court ruled that race-based transfer requirements violated violated the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The absurdity of Edmond’s case – a child being denied access to a public school because of his race – underscores the difficulty of reconciling decades-old desegregation efforts with the proliferation of charters and other school choice options. Should the decades-old logic of desegregation still apply when the government no longer has the sole power to dictate where children go to school?

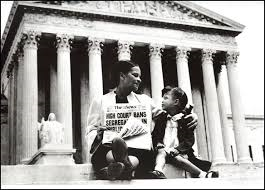

Brown v. Board of Education officially dispelled the fantasy of “separate-but-equal.” In the decades that followed, school districts across the country, primarily in the South, used a combination of busing mandates and school choice schemes to level the racial balance of their schools.

After years of legal battles over school integration, educators in St. Louis signed a desegregation agreement in 1983 to improve racial integration by voluntarily allowing black students to transfer to whiter suburban districts. The rules also allowed non-black students to transfer to inner-city public schools.

Even today, students like Edmund are hardly the norm. Some 4,500 black students transfer out of the city, while only 140 non-black students transfer in. David Glaser, head of the Voluntary Interdistrict Choice Corporation, told St. Louis Public Radio that he was unaware of any other case where a black student living in the county wanted to attend a school in the city. But it reveals a tension that could become relevant elsewhere.

The magnet schools and other choice programs that accompanied desegregation are being joined by new ones, like charters. Just a generation ago, it would have been hard to imagine that students like Edmund could be drawn back to the inner-city schools.

Meanwhile, the drive to create racial balance in every school is motivating a fresh round of lawsuits and legal investigations challenging charter schools and vouchers.

School integration is about more than numerical balance, though. It’s also about the underlying imbalance of power.

Desegregation succeeded when it prevented whites from standing in the schoolhouse door, blocking children of color from attending the best schools in their cities. Successful charter schools and other forms of school choice can also help correct that imbalance, empowering children previously denied opportunities to attend schools that would serve them well — as long as well-intentioned rules don’t block them.