Students in Ohio’s online charter schools perform worse than their peers in brick-and-mortar schools, and they weigh down statewide charter school performance, a new report by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute finds.

The findings, which jibe with an earlier national report by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes, add new fuel to the debate over virtual charter schools that tends to split the school choice movement.

Ohio’s charter school students tend to lag behind their traditional-school peers in academic growth, on average. But a growing number of charter school students in the state attend full-time virtual charters (known as e-schools in Buckeye parlance). The Fordham study finds students in e-schools make slower academic progress than their peers in physical classrooms, both charter and otherwise — even after controlling for student demographics and past academic performance. As a result, e-schools “drag down the impact of the state’s charter sector.”

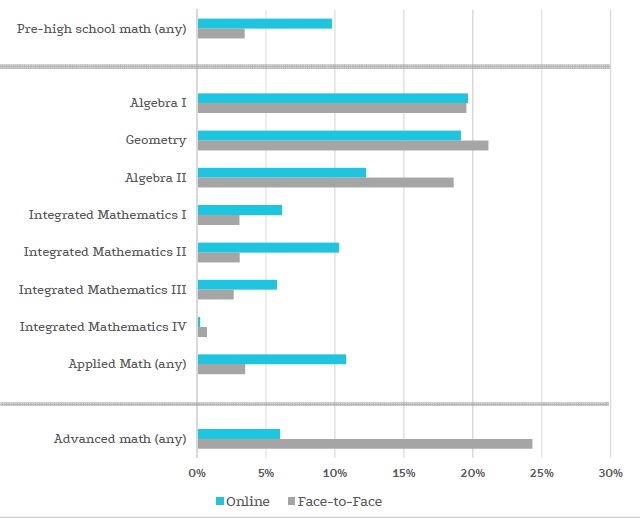

Ohio is one of the “big three” states for full-time virtual charter schools. By focusing on a single state, the Fordham report paints a fuller picture of online students. It finds they’re concentrated heavily in urban areas and on the periphery of major cities — places where they presumably have access to brick-and-mortar charters and other school choice options. They tend to be struggling students who are behind on credits. And they’re significantly less likely than their peers on physical campuses to enroll in advanced courses.

Florida is one example: The state-run Florida Virtual School offers online courses that are available to students enrolled in brick-and-mortar public schools. Florida students can also take fully online courses offered by any district in the state, or by a handful of approved external providers (who must demonstrate prior success with online courses), as long as they remain enrolled in their home brickand- mortar school and district. There is no fee for students and no limitation on the types of courses they can take (as long as they are academically qualified), and districts are not allowed to restrict students from enrolling. In other words, the system functions as one giant online school.

This recommendation is likely to get a warm reception from online learning advocates, who typically want states to offer students diverse ways to access virtual courses.

More controversially, the report says policymakers should at least consider allowing online schools to “select students most suited to their programs (and most likely to benefit from them).” State laws tend to bar charter schools from “cream skimming,” but perhaps it makes sense for online schools. On one of our recent podcasts, a leader in the virtual education industry pushed back on this idea:

“It is absolutely true that there are students in our schools for whom they are not a good fit, and if they were my children I would pull them right out and put them back in a traditional classroom,” [Connections Education co-founder Steven] Guttentag says. “But they’re not my children. They’re somebody else’s children, who decided this was best for their child.”

Here’s how the report addresses those concerns:

Some might worry that selectivity violates the principle of self-selection that guides school choice, but the choice process also requires that students have enough information to determine whether they fit in a particular program. In the case of e-schools, this information is not about a special program or curriculum, but rather about the specific demands of the virtual instructional configuration. At the very least, e-schools should actively recruit students most likely to succeed in a fully online learning environment (or students who the schools believe they can sufficiently orient and support).

Which students can succeed in full-time virtual schools? Who should decide, and how? These questions get at some of the big issues that arise under the new definition of public education.

Some students might be self-motivated and able to thrive at home in an online environment. For other students, like those with medical issues, full-time virtual schools might be the best possible option, period, and their life circumstances might hinder their academic performance in ways that are hard for studies to capture. But the report adds:

On the other hand, some e-school students may actually be least suited to thrive in an online learning environment. If they failed in brick-and-mortar schools because they lack self-motivation, independent learning skills, parental support, and/or a quiet, stable place to do schoolwork, they are even less likely to do well in a virtual school.

The bottom line is that online providers need not use their unique student population as an excuse for their performance. Instead, they must tailor the way they deliver content and provide academic supports to maximize student success.

These are things people in the online education industry say they’re working on. It’s one reason many Florida districts and virtual schools have embraced in-person support for their online students. It’s why K12 Inc. says it’s overhauled its orientation process for new students. And it’s a reason some online learning advocates believe in trial periods that allow students to enroll in full-time virtual schools for a few weeks or a couple months, after which schools advise students on whether they’re likely to do well over the long haul.

But these are things the online learning industry doesn’t seem to have totally figured out. There’s still a lot we don’t know about how online teachers and students spend their time, what support struggling students need in virtual schools, and how to equip their families to support their learning. The Fordham report notes: “These are questions that are largely unexplored in the research literature.”