A key thread connects many of 2016’s biggest political conflicts over school choice: Money.

In Nevada, the nation’s most ambitious educational choice program was challenged in court, and technically prevailed, but it may still wither away unless lawmakers agree to fund it.

In Louisiana, lawmakers cut funding to a statewide voucher program, leaving hundreds of students in the lurch and sending state officials scrambling for a temporary fix.

In Massachusetts, opponents blocked a bid to allow one of the highest-performing charter school systems in the nation to expand. A crucial part of the argument was that more charters would undermine the funding of existing public schools.

Episodes like these have many reformers arguing that overhauling education funding could be crucial to the future of the school choice movement.

“Our school funding system in the Unites State for K-12 education is fundamentally broken, and in my opinion it is the biggest barrier to enabling and having a diversity of school choice,” Lisa Snell, the director of education and child welfare at the Reason Foundation, said last month during a gathering of education reformers in Washington.

Many private school choice programs — including the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program in the nation’s capital — are funded through standalone pots of money that insulate them from public schools. That means their backers, and the families that rely on them to pay tuition, have to ask for annual appropriations and leaves them vulnerable to shifting political winds.

The new definition of public education depends on funding systems in which money truly follows individual children and districts are able to thrive even as more students attend non-district schools. Snell said scholarship programs should be designed to avoid this problem. When parents sign up to enroll their children in private schools with the help of a Florida McKay scholarship or a voucher in Indiana, they receive funding automatically — just like public schools, including charters. If lawmakers take no action, families still get scholarships.

Ensuring money follows the child, however, raises another issue: The impact on existing public schools.

What’s the harm?

Everywhere public charter schools or private school vouchers are up for debate, opponents seem to have a constant refrain. They “divert” money from school districts. They “drain” resources away. They harm students “left behind” in traditional public schools.

These claims can be politically potent. But they often fall apart under scrutiny.

In Florida, opponents of tax credit scholarships have repeatedly asserted the nation’s largest private school choice program harms public schools, but they’ve struggled to substantiate that claim in multiple lawsuits. (Step Up For Students, my employer and the publisher of this blog, helps administer the scholarship program.)

Studies have consistently shown the program saves the state money, in large part because tax credit scholarships offer each student less money than public schools receive per pupil. Research on school vouchers from Louisiana to Wisconsin points to similar conclusions. But that leaves a larger question unresolved. What if students, given a choice of private school choice programs, new public charter schools or other options, leave traditional schools en masse? Will that leave school districts strapped for cash? Will the loss of students leave them saddled with expenses they can no longer afford to pay?

A new report released late last year by the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute suggests the answer is: Not necessarily.

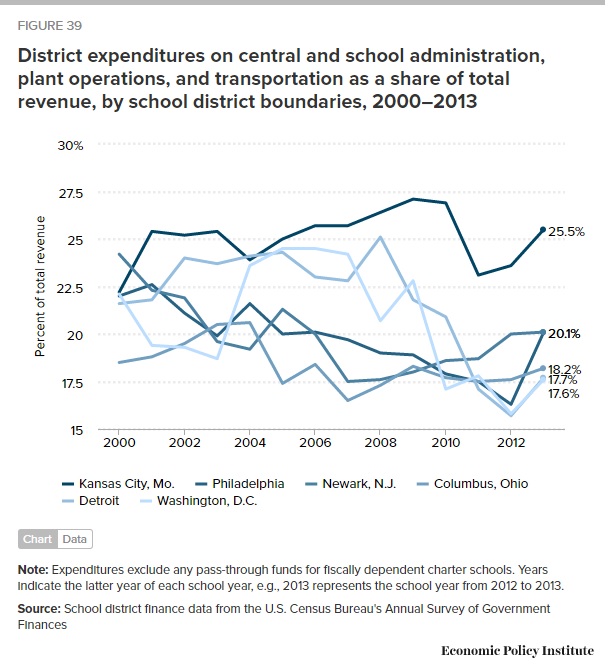

Despite press releases that raised grave concerns, the report found little evidence that charter school growth undermined the efficiency of school districts in cities from Detroit to Philadelphia. By multiple measures, from overhead spending to student-to-teacher ratios, districts didn’t seem to suffer as growing numbers of children left their schools for charters. By and large, they managed the shift efficiently.

Georgetown University professor Marguerite Roza has argued states should fund schools based on the students who attend, and schools should set budgets in ways that allow them to expand or contract as students come and go. Such a system, she has written, would also help districts manage the growth of charter schools.

Building for the future

Bruce Baker, the Rutgers University professor who authored the report for EPI (a think tank that receives some of its funding from teachers unions), wrote that the growth of charter schools might harm districts in ways his data don’t capture (this article drives home those points).

His report points to another multi-billion-dollar issue: Facilities.

Florida funds public schools using on a statewide formula in which money largely follows individual students. But school districts largely pay for their own school buildings, using billions of dollars a year in tax revenues that, for the most part, don’t follow students if they decide to enroll in charter schools.

For school choice critics, the money school districts spend on school facilities can help build the case against charter school expansion. What happens if they take on debt to construct new schools, and take 30 years to pay it off, only to watch their students — and the money that comes with them — wind up in charters, or other schools the district itself doesn’t operate?

As Baker notes in his report, communities considering charter school expansion need to think about “protecting the taxpaying public’s interest in land, facilities, and other major capital assets acquired on the public dime, over the long term.” The same applies to private school choice.

Under the new definition of public education, a school district is no longer the only entity that educates children. So why should it have a monopoly on publicly funded buildings?

One idea, first proposed years ago, has not yet been tried. Each city or county could set up an independent facilities commission that would control all school buildings. If one school shrank, other schools, including charters, could make use of the space. Charter schools would be on the same footing as other public schools.

There might be other benefits to this approach. For example, there’d be less risk that for-profit charter schools would somehow profit from their real estate.

During a session at the Foundation for Excellence in Education’s annual gathering in Washington, Roza said if the public is going to keep funding school buildings, it’s important that the use of those buildings can change over time, because public education is changing far faster than buildings can be build built or long-term construction debts can be paid. The system needs to be ready to adapt.

“We’re talking about education in 2036,” she said. “We know there will be students, which is why we encourage people to fund students. There will still be students learning, but the rest of the equation, we don’t know.”