Note: See a detailed response to the Orlando Sentinel from Step Up For Students here and a quick summary here. Step Up helps administer Florida’s Gardiner and Tax Credit Scholarship programs, and publishes this blog.

One of the schools singled out by the Orlando Sentinel’s investigation of private school scholarship programs was founded by a couple who grew frustrated when their son, burdened with severe medical issues since birth, continued to struggle in public school.

Five years later, its standardized test scores show students tested in each of the last two years are, on average, making double-digit academic gains.

The Sentinel didn’t mention this in its description of TDR Learning Academy, a K-12 school in Orlando that enrolls about 90 students who use tax credit scholarships for low-income students, McKay scholarships for students with disabilities, and Gardiner scholarships for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome. Instead, in both its story and accompanying video, it portrayed the predominantly Hispanic school as a poster child for a regulatory accountability system it suggests is far too lax.

“These schools operate without state rules when it comes to teacher credentials, academics and facilities,” says the narrator in the Sentinel’s video. “TDR Academy in Orlando is one of them.”

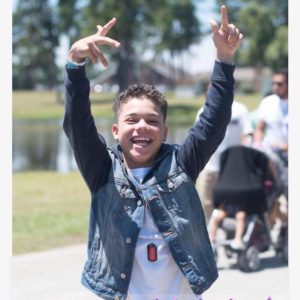

Hector and Melissa Sanchez started TDR in 2012 when their son Isaiah was in fifth grade. Isaiah was born without the left ventricle of his heart, a condition that has led to a lifetime of surgeries. According to Melissa Sanchez, he suffered a stroke during one surgery, resulting in years of seizures. He suffered a cardiac arrest during another, which deprived his brain of oxygen for 48 minutes. He didn’t learn to walk until he was three. He can only hear with one ear.

Not surprisingly, Isaiah has learning disabilities tied to his medical history. He was retained in Kindergarten, then retained again in third grade, Sanchez said. At one point, she said, school officials told her the Florida Department of Children and Families might have to investigate, because Isaiah was missing too much school. Among other reasons, he and his family were making frequent trips to Shands Children’s Hospital in Gainesville.

Sanchez said she and her husband decided they had to do something different. They opened their own school, hoping to help their son and children like him. They started with 12 students. Now they have 92.

“We have so many parents who tell us how blessed they are to have this,” Sanchez said. “School was a horror movie they were living in, and their children were living in. Now they love being in school.”

Sanchez said she and her husband gave up pastoring a church so they could tend to Isaiah’s needs. Two years ago, he had a heart transplant. Now 17 and in 10th grade, he still struggles in some subjects but has a shot at graduating with a standard diploma, said principal Bryan Gonzalez.

The Sentinel noted Gonzalez is 24 years old, a student at Valencia College, and the Sanchez’s son-in-law. All true.

The newspaper also noted some of TDR’s teachers do not have college degrees. Also true.

But there’s more to the story.

Gonzalez said he took over as principal in January 2016, after the previous principal, who had a master’s degree, abruptly quit. He quickly determined that while some teachers were boosting math outcomes, others were not – and that there wasn’t much correlation between educational degree and math proficiency. Instead of relying on a degree as an indicator of quality, Gonzalez said he installed a math test as part of the hiring process.

Currently, five of TDR’s seven teachers have bachelor’s degrees, he said. Of the other two, one is an engineering student at the University of Central Florida who has passed Calculus III. The other is studying to be a physician’s assistant, but currently taking a break from college.

Gonzalez said Sentinel reporters asked whether TDR teachers had college degrees. He said some did, some didn’t. He said they didn’t ask for details. He said they didn’t ask for test results.

Gonzalez said the reporters visited his school twice – the first time for 30 to 45 minutes, the second time for 15 to 20 minutes.

The Sentinel noted TDR uses the A.C.E. (Accelerated Christian Education) curriculum, which is heavy on worksheets and has its share of detractors. Again, true.

But for students who have been at the school in tested grades the past two years, standardized test scores show, on average, double-digit gains in percentile rankings in math, reading and language arts, according to results analyzed by Carol Thomas, Step Up’s vice president for the Office of Student Learning and a former deputy superintendent in the Pinellas County School District. Many of TDR’s students began in the bottom quartile. Many remain below average. But the results show strong progress.

The Sentinel didn’t quote any parents whose children attend TDR.

Eileen Caraballo is one of them. Her son Abisai has ADHD and autism.

Abisai was enrolled in his neighborhood public school for kindergarten, but Caraballo said his experience there was a nightmare. Instead of working with her on how to best handle his tantrums, school officials routinely sent him to the principal’s office. She said she worried, daily, if the phone would ring and she’d be asked to come pick him up. Finally, she said, she secured a McKay Scholarship and, after researching multiple schools, decided to give TDR a shot.

Now in his third year, Abisai is a different child, Caraballo said. TDR worked with her to structure the kind of regimented schedule he prefers and learned how to calm him without punishment. His meltdowns became less frequent. His reading prowess improved. Now he’s going through books “like water” and reading far above his grade level, Caraballo said.

“It was such a good feeling to know he’s at school, and he’s learning, and he’s cared for,” she said. The teachers at his prior school might look better on paper, she said, “but they don’t know how to care.”

My child EXCELS at the private Christian school he goes to!! I thank God for his school, the teachers the administration and all the volunteers and church members that make, in my opinion, a TOTAL SUCCESS !!!!!!

My my, This ignorance is truly a shame. Orlando Sentinel, who is in the wrong here? If in fact the findings are true and accurate in all accounts. The school is accountable. Not the state, or government. And by all means certainly not the parents! So now who to blame. The program? Really the very same programs that allow for all parents to choose where and how to educate their children as individuals? As far as the funding is concerned, it belongs to all of our children just the same as children that attend public schools, charter schools. Personally, I believe some education on your ( Orlando Sentinel ) part is in order. In the future consider standing up for your children and grandchildren. Don’t bash the very same system that allows your kids an education. Let’s think before we write…