It all begins with a song Mandy Johnson sings to her third-grade students to help them remember key math concepts.

“Area is two squares inside,” she sings. “What is the perimeter?”

She reinforces the repetition of the songs with worksheets students must complete every morning on key concepts. Johnson said this has helped students better retain the information.

Johnson said she has access to different math programs, which are not available in other public schools.

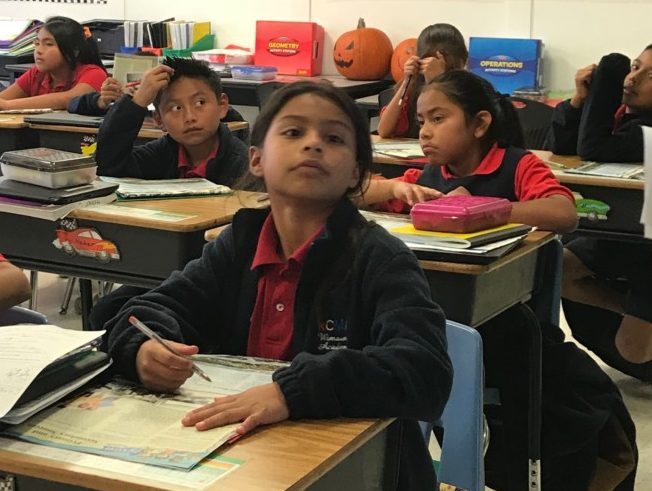

Indeed, the third-grade class at this low-income migrant school in Hillsborough County outscored every other third-grade class in the district on last year’s state math assessments. Ninety-eight percent of Wimauma students are Hispanic. Nearly all are considered economically disadvantaged. More than four-fifths are classified as English language learners.

The third-grade class at this Hillsborough charter school, founded to serve the children of migrant farmworkers, was one of only 12 groups of third-graders in the state that demonstrated 100 percent proficiency on the FSA math test. Overall, scores at the school also tend to be higher than average.

Johnson said her students have a real hunger for learning.

She holds Saturday classes for students. She invites them to come in for extra help during recess. On a recent day, she said 13 students showed up for extra instruction. According to the Florida Department of Education, in 2015-16, just 2 percent of the student population at RCMA Wimauma Academy was absent 21 days or more.

If a student is slipping in academics, school officials are immediately on the phone with his or her parents. The school holds many community events, from a fall festival to soccer tournaments. Many parents attend the events and build a bond with staff.

On a sunny day this October, students were celebrating the Day of the Dead in honor of their deceased loved ones by singing songs, eating traditional bread and reading a story in Spanish. They also displayed artwork.

“Nobody gets lost,” said Juana Brown, director of charter schools at RCMA. “If someone is having a rough day (our director of student affairs) will pick up the phone and call the family. She knows the mother. The mother knows her. We are not waiting until progress reports. We are having constant communication with parents.”

Walking around the school, students greet teachers in red, bright uniforms. The school’s classrooms are separated by a garden the students helped plant.

Connections matter

Brown helps oversee three charter schools in two counties more than 100 miles apart. But that hasn’t stopped her from cultivating personal connections with students. Returning from gym, many of the students stopped in single file to give her a high-five, and greet her by name. One student wanted to remind her that she had a doctor’s appointment and needed to leave early.

“Are you OK?” Brown asked with a smile.

The girl nodded as she walked back into the classroom.

Visiting the lunchroom, many students sat around giggling as they ate. But there was one young girl who was sitting not wanting to touch her food. She began to cry.

Immediately Brown came over to her and asked her why she was sad. The girl couldn’t speak, continuing to look down at her food.

Brown asked the lunchroom teacher on duty to come over and speak to the girl, a concerned look on her face.

The teacher calmly approached the student, listening intently to the girls’ concerns over the crowded lunchroom.

After sharing her concerns and receiving advice from the teacher, the girl stopped crying and while still a bit somber, she began to brighten back up.

Student engagement and parental involvement have helped RCMA Wimauma Academy excel, school officials said. It improved its school grade to a B earlier this year.

But the reasons for the school’s results go beyond those two factors. School officials talk about supporting the whole child with good nutrition and a strong community. They emphasize understanding the struggles of students growing up in rural poverty. They provide students individual attention, with 17 to a classroom. Most classrooms also have a teacher’s aide.

‘We cherry-pick the neediest families’

Sixty-five percent of RCMA Wimauma Academy students are children of migrants. Many are undocumented. That can create challenges for educators. But RCMA works to turn them into assets.

“Some of our children speak three languages: indigenous language, Spanish and English,” Brown said. “We integrate into our curriculum celebrations and traditions that are part of the community. By doing these celebrations, we give children a sense of place, belonging and the richness of culture they are part of.”

Brown said the school understands the academic and psychological difficulties of living as a migrant family. Many of them move throughout the country in search of work.

“We opened the school also with the understanding that these children are from families who have a level of anxiety and stress not just because of poverty but also because of mobility,” Brown said. “You pick up and you travel with your parents. You are not packing the entire home and you pick up what you take and you may go to Tennessee, Michigan or Georgia.”

Brown said that as a charter school, it allows her to serve a specific population in need with an intentional program. She takes issue with the criticisms that charter schools cherry-pick students.

“If we cherry-pick, we cherry-pick the neediest families,” she said. “We don’t operate for profit. We have to raise funds.”

Two generations

Monica Alarcon’s two sons attend the academy.

“The most important thing is they give attention to the kids’ needs,” she said. “I feel they are safe there. I am not worried.”

Alarcon attended the school herself 20 years ago, but could not finish. Her parents separated when she was 15 years old. As a result, she had to stay home and cook for her father and take care of payments.

She said the school’s current principal, Mark Haggett, was her math teacher at the time. She recalls how he helped her when she struggled in class.

Alarcon, a stay at home mom whose husband works in the construction business, said her children never complain about the school. In fact, she said they want to go even when they are ill.

Living day to day is a struggle for migrant families, Brown explained, because they are paid based on how much they pick in the fields.

As a result, school officials make sure they provide breakfast, lunch and snacks to students. They also have a community pantry parents can visit to receive food when they are short.

Medical care is another issue that is a challenge for the working Hispanic poor.

“Not all our children’s families will get Medicaid because (they) are the hidden population,” Brown said.

Asked about the school’s long-term goals, Estevez said she hopes one day to open a high school for her students.

An organization for migrants

RCMA opened in 1965 after farmworkers had no other choice but to take their children with them into the fields, exposing the youngsters to pesticides, snakes and machinery.

It’s primarily a childcare provider, which serves 7,000 children in 21 counties. In 2000, the organization opened charter schools in Wimauma and Immokalee.

About 80 percent of RCMA’s parents work in the farming industry. The average family makes approximately $16,000 a year, which is considered deep poverty. Located off U.S. Route 301 in an area surrounded by agriculture and farmland, Wimauma Academy serves 224 students in Kindergarten through fifth grade.

Marcela Estevez, director of student affairs at RCMA Wimauma, said there is a strong connection between the parents and the teachers.

“They trust the school,” she said. “They know this door and principal’s door are always open. There is always someone that is going to listen to them.”

And the parents understand the importance of educational opportunities they may not have had themselves.

“They want their kids to have a different life than the life they had,” she said. “They want their children to succeed.”

Disclosure: In 2010, RCMA received $100,000 from John Kirtley, chairman of Step Up For Students, the nonprofit that oversees tax credit scholarships in Florida and the co-hosts this blog. Another $100,000 came from a Walton Family Foundation grant. The academies also have numerous community partnerships, such as the one with Gary Wisnatzki of Wish Farms in Plant City that brought the school $300,000.

[…] continue reading. […]