We’ve written before about the improving results in Miami-Dade County Public Schools, and the potential for improvement in Duval County.

The latest results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress show those positive trends continue. But they also show there’s still work to do.

Urban school districts may have shown slightly more improvement than the nation as a whole, where results were largely stagnant.

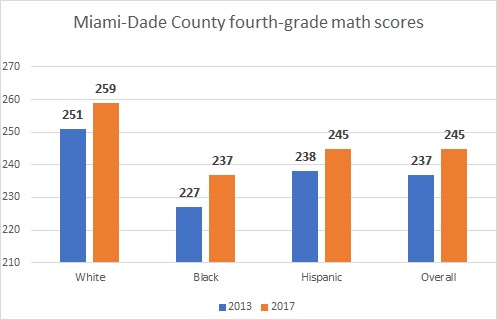

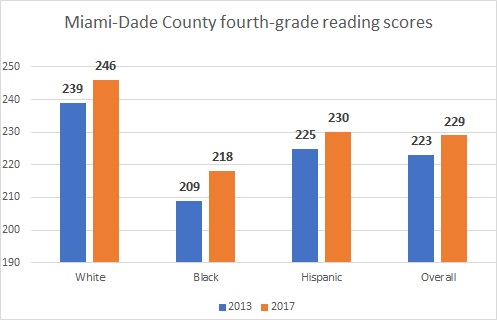

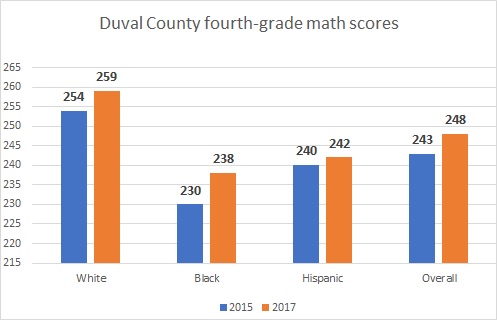

The three Florida districts included in the Trial Urban District Assessment results provided their share of bright spots. In fourth-grade math, for example, Miami-Dade and Duval were two of just four districts that posted statistically significant score increases.

In both places, disadvantaged students helped drive increases.

Experts caution against using scores like the national assessment results released Tuesday to gauge things like the effects of specific policies or the performance of district leaders. However, the numbers paint a useful picture of how three Florida urban districts are doing.

Miami-Dade feels the love

Fresh off a drama-filled decision to keep his talents in South Beach, Miami-Dade County Public Schools Superintendent Alberto Carvalho took something of a victory lap in D.C. National commentators lauded the continuing school-improvement “fiesta” in the nation’s fourth-largest school district.

During a symposium on the results, he said his district focused on recruiting top principals and adopting an ambitious curriculum.

Miami-Dade posted statistically significant gains in fourth-grade reading and math. Some groups — like black students — made outsize improvements, helping narrow achievement gaps.

In reading, scores for black fourth-graders drove the district’s overall improvement.

During the symposium, Carvalho told Cindy Marten, the superintendent of San Diego’s schools, that he envied her district’s math results. This chart shows why:

As the #NAEPDay TUDA event begins, here is a snapshot of math and reading performance for panel participants @MDCPS, @AustinISD, @sdschools, and @ChiPubSchools. pic.twitter.com/6ngkNXF1fC

— NAEP (@NAEP_NCES) April 10, 2018

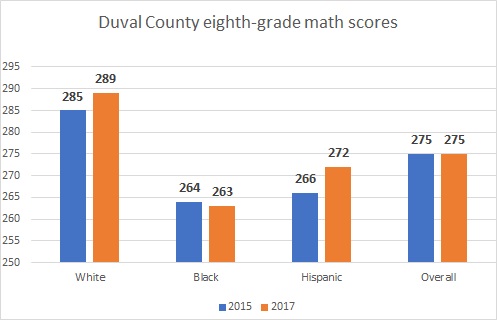

Eighth-grade math remains Florida’s biggest stumbling block on nationwide assessments. Gaps between racial and ethnic groups remain wide — even in districts like Dade that have much to be proud of.

Duval doing better?

The school district that shares its borders with the city of Jacksonville started participating the urban-district assessments in 2015.

Like in Miami-Dade, improvement among black fourth-graders outpaced improvement among other groups and helped drive positive numbers for the city as a whole.

In fourth-grade math, they were the only racial or ethnic group that saw statistically significant progress.

In eighth grade, the news wasn’t as good. Average scores remained the same, and individual groups were a mixed bag.

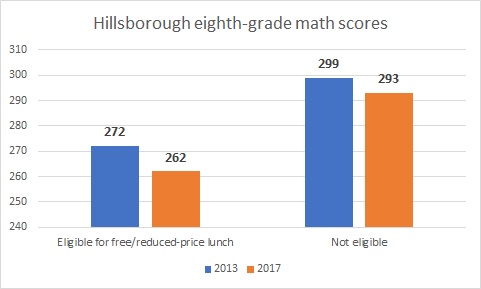

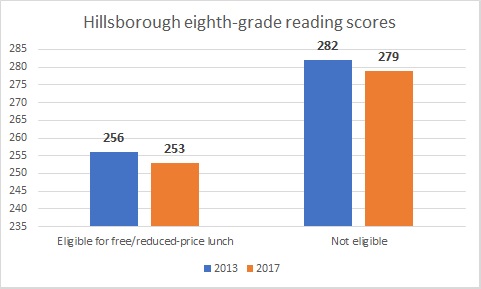

Hillsborough hits a snag

Much like Dade and Duval, the district that includes Tampa was at or near the top of the class in several categories of raw test performance. Its eighth-grade reading scores led the urban districts included on the Nation’s Report Card.

Some trends and numbers for student subgroups paint a less-rosy picture, particularly in Florida’s problem area, eighth-grade math.

In other areas, trendlines were basically flat.

By themselves, these data don’t lend themselves to tidy conclusions about leadership or policy. But it’s worth taking a measure of where things stand. The situation in Florida’s large school districts isn’t as bleak as some critics might claim, but the work isn’t over, either.