This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

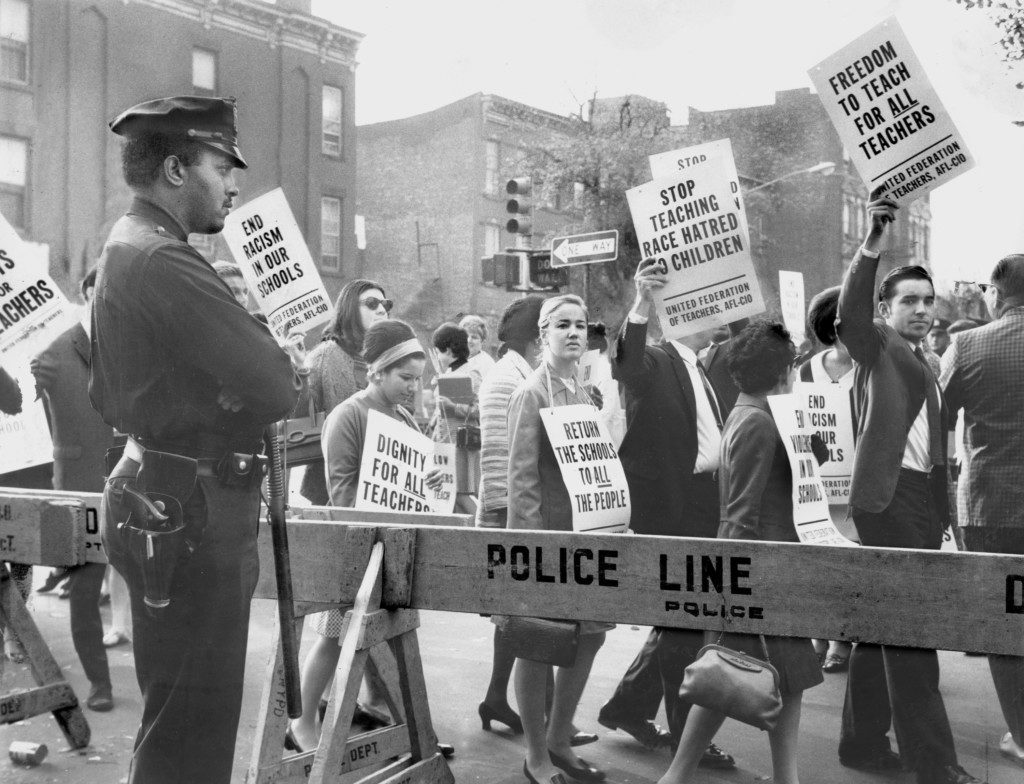

The crowd shots that illustrate the Democratic Party’s big split over school choice are, in one key respect, starkly black and white. Or, at least, black, brown and white.

On one side: Thousands of teachers on strike, from West Virginia to Oklahoma to Arizona. Overwhelmingly white.

On the other: Thousands of parents at school choice rallies, from Florida to New York to Illinois. Overwhelmingly black and Hispanic.

On the other: Thousands of parents at school choice rallies, from Florida to New York to Illinois. Overwhelmingly black and Hispanic.

None of these recent events happened at the same time. And to be clear, last spring’s strikes were primarily for better pay, not against school choice. (Though unions and their allies haven’t been shy in trying to scapegoat choice for skimpy raises, hot air, gang violence … ) But 50 years ago, these Democratic camps were face to face, over picket lines in The Big Apple, over competing visions of public education. That epic power struggle helped set the stage for today’s divide over school choice.

The battle over “community control” rocked the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn in 1968. It pitted the predominantly white teachers union in New York City, led by Al Shanker, against black and Puerto Rican parents.

Tired of white resistance to court-ordered integration, communities of color in NYC decided to pursue an alternative. They pushed for changes in local governance, resulting in a pilot that created a community-based school board.

Community control wasn’t school choice, but the movements share roots.

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian James Forman Jr. notes a few in “The Secret History of School Choice: How Progressives Got There First.” Community control advocates were tired of ceding to bureaucrats. They believed empowered community groups, closer to students and parents, could better create successful schools. Forman even likened the community school board in Ocean Hill-Brownsville to another revolutionary institution of that era, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

It didn’t take long for the pot to boil over. In May 1968, the administration at one community school, P.S. 271, fired 13 teachers and six administrators it deemed ineffective. All but one were white.

The union response was shock and awe. Shanker called three strikes that paralyzed the city. More than 50,000 teachers went on strike. More than 1.1 million students were stranded.

White parents were outraged. But they blamed minority communities, not striking teachers.

According to one teacher who backed community control and worked in P.S. 271, white parents stood by white teachers, even though community control would have given them more power over their neighborhood schools, too. Wrote Charles Isaacs in “Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville,” “They were acting as whites first, and as parents second.”

Things got ugly all around, but Isaacs’s account makes clear the union stoked racial tensions.

It distributed one leaflet that claimed teachers in P.S. 271 were “teaching the three R’s of Racism, Rioting and Revolution.” It distributed a half million copies of another, allegedly created by a community control supporter, that reeked of anti-Semitism. “We are not about to let our school system be taken over by Nazi types and gangsters,” Shanker said at a rally. American schools are in danger of being taken over by “black separatists,” he warned in a speech.

All this had the desired effect on union members. But split screens zooming out to the big picture would have captured another reality.

The community in Ocean Hill-Brownsville loved the school, its leadership, its multicultural teaching corps – and its newfound power. Battling side by side strengthened bonds. Empowerment spurred engagement. Said another teacher in P.S. 271, activist Les Campbell (who later changed his name to Jiti Weusi):

“We had shown that this downtrodden community, faced with a crisis, using its own resources, could overcome, and there was a feeling of jubilation. … I used to walk through the streets of Ocean Hill at that time, and it was so beautiful. Parents used to come up and tell me to come in their house and have some fish, or have some chicken, or have some coffee, or have a cold drink. These were parents who were pouring out their heart to people who they felt were doing something to educate their children.”

The jubilation didn’t last. Shanker won.

In the wake of their victory in NYC, teachers unions flexed their new muscle nationwide. Within the Democratic Party, they increasingly dictated education policy and undermined support for school choice.

The shift was swift. Jimmy Carter told Catholics on the campaign trail he supported vouchers, then backed down after receiving the first-ever endorsement from the NEA. Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton told Wisconsin state Rep. Polly Williams he was fascinated by vouchers, but a few years later, President Bill Clinton opposed them.

Fifty years after Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Democrats are still torn. The still-overwhelmingly-white teachers unions still demagogue alternatives to traditional public schools, and still enjoy support from white progressives. But Democrats of color continue to support options, even in the face of union opposition, and to benefit from them in growing numbers.

But for Trump, this split would still be festering in the open, as it did under Obama.

The unions should thank him.

Ron–This quote, “They were acting as whites first, and as parents second,” is a powerful reminder of how race and class impact how we perceive and understand the world. I wish more white progressives were open to learning about the history of parental choice and the political Left. I may be a naïve dreamer, but I believe white middle and upper-class progressives will eventually find common ground with low-income communities of color in the area of parental choice in education. It just may take a while.

Great piece…thanks.