Who said the following?

“It’s time to admit that public education operates like a planned economy, a bureaucratic system in which everybody’s role is spelled out in advance and there are few incentives for innovation and productivity. It’s no surprise that our school system doesn’t improve: It more resembles the communist economy than our own market economy.”

“… After decades of failure, even the Soviet bloc seems to have concluded that only markets work, that a system without incentives and rewards drives out the good and favors the mediocre.”

Ronald Reagan? Rush Limbaugh? Milton Friedman?

Today, it’s hard to imagine that those words could be penned not by a right-winger, but by the liberal leader of a national teachers union.

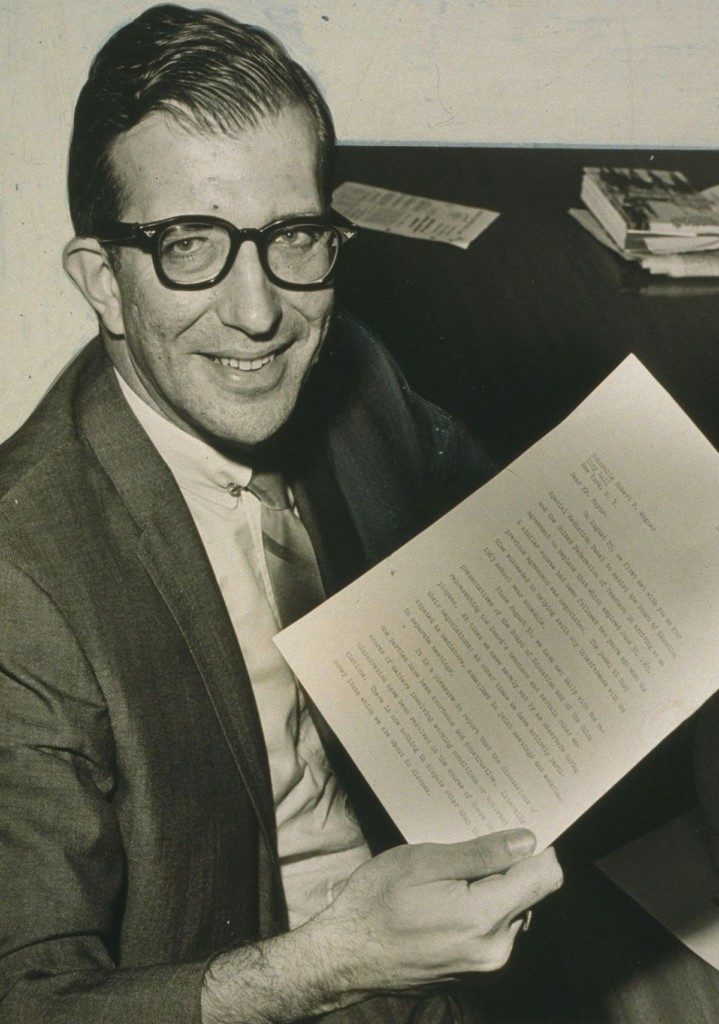

Albert Shanker was president of the American Federation of Teachers when he wrote that scathing critique of the public education system in his weekly advertorial in The New York Times, July 23, 1989 (“Put Merit in Merit Schools”). Although he proceeded to criticize Republican President George H.W. Bush’s proposal to spend $500 million on rewarding “merit schools” that had improved academically in one year, he did so not from a partisan perspective or by dismissing it out of hand for ideological reasons. Rather, he feared the plan didn’t go far enough.

He wanted to extend the funding over five years, to give schools the time to make “meaningful changes.” Those included allowing participating schools “to be free to try new ideas,” which would require the waiving of “all regulations” except for those dealing with health, safety, and civil rights. Unions “would have to grant staffs the right to waive provisions of union contracts that get in their way.” Each school would have “total control” over its budget, with no interference from school boards.

Finally, because this radical experimentation would (hopefully) result in schools with diverse offerings competing against each other, Shanker noted that it was imperative that parents have the freedom to choose among them.

Although he acknowledged there likely would be difficulties in the early going, Shanker believed the long-term benefits would be manifest: School staffs working as teams, trying new methods and making “painful decisions they now avoid.” Using higher salaries to attract better teachers to shore up weak areas. Engaging the community. Focusing on student learning.

“It’s the same as in any team activity or business,” he wrote. “If there’s something in it for everybody, people are much more open to change.”

This was a potent elixir from a man of the left nearly 30 years ago. Today, it would be considered pure poison to entrenched interests. It’s impossible to envision current AFT President Randi Weingarten challenging her membership that way. Equating education with markets? Why, that’s Koch brothers propaganda!

To be sure, Shanker’s views on education reform were notoriously complex and evolving. Despite his heterodox advocacy of experimentation in school choice, accountability standards, and merit pay, he never wavered from his commitment to organized labor, and he could be ruthless in pursuing his goals. (His reputation was such that in Woody Allen’s 1973 film “Sleeper,” the main character wakes up 200 years in the future and is informed that the previous world was destroyed when “a man named Albert Shanker got hold of a nuclear warhead.”) In the late 1980s he embraced the nascent concept of charter schools because he believed they would give teachers the flexibility they needed, only to renounce them later because, in practice, most were not unionized, and many failed to advance his vision of social mobility and integration.

Of course, Shanker wasn’t the only one whose opinions changed. The Reagan administration initially was tepid to the idea that charter schools were needed. William Kristol, the longtime conservative pundit who back then was the chief of staff to Secretary of Education William Bennett, argued “we think there is lots of evidence that traditional methods are working.” The distance between that statement and Betsy DeVos seemingly can be measured in light years.

If Washington in the Madonna era was a bit slow to board the school reform train, Shanker was trying to get in front of it before it gained steam. A man of intellectual curiosity, Shanker often identified political and social changes before they became trends and sought to position his organization early enough to influence them to his members’ benefit. His initial interest in charter schools, and his 1989 column advocating utilizing market forces and parental choice to improve public education, are examples of a leader attempting to ride a wave on the horizon instead of waiting for it to break on the shore.

The ripples of reform go back at least to 1955 when Friedman first proposed school vouchers. In 1978, John E. Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman, law professors at the University of California Berkeley who leaned to the port side of the political spectrum, published their book “Education by Choice: The Case for Family Control,” which anticipated several of today’s education reforms.

A year after Shanker’s “Put Merit in Merit Schools” column, John Chubb and Terry Moe of the centrist Brookings Institution published “Politics, Markets and America’s Schools,” which similarly called for a market-based approach to education reform. They even echoed Shanker’s rhetoric, identifying the “dysfunctions of bureaucracy” and the “value of autonomy,” and how principals and teachers need to “exercise their expertise and professional judgment” by having the “flexibility” to “operate as teams.”

In retrospect, the contemporary confluence of opinion between Shanker and Chubb/Moe, among others, seems like a lost opportunity to seed common ground. The education reform movement that was but a green shoot in the 1980s has become a mighty oak. Its branches include charter schools, vouchers and tax credit scholarships, home schooling, virtual learning, and other alternative delivery systems that give families the freedom to tailor education opportunities to their children’s needs. Nevertheless, school choice continues to be a subject of intense political conflict.

The confident belief in the virtue of change expressed by Shanker three decades ago is in stark contrast to the dogmatic defense of the status quo by his successors. Whereas Shanker, like Chubb/Moe, saw the burgeoning desire for reform as potentially empowering — a way to unshackle teachers from the bureaucracy and unleash their potential — today’s unions view such attempts as threats. For many, change is the enemy, not a tool to benefit all stakeholders.

Teachers who complain about government diktats from state capitols have natural allies in choice advocates who want to decentralize command and control. Albert Shanker understood that, and thus the need for systemic change, more than a generation ago. He may have been ahead of his time (and his membership), but it’s not too late for educators to incorporate his ideas.

(Hat tip to former RedefinED editor Travis Pillow, whose research and original unpublished work inspired this post.)