Scott Kent’s recent redefinED post on Al Shanker’s New York Times column comparing our public education system to Soviet-style communism has raised eyebrows — and many questions.

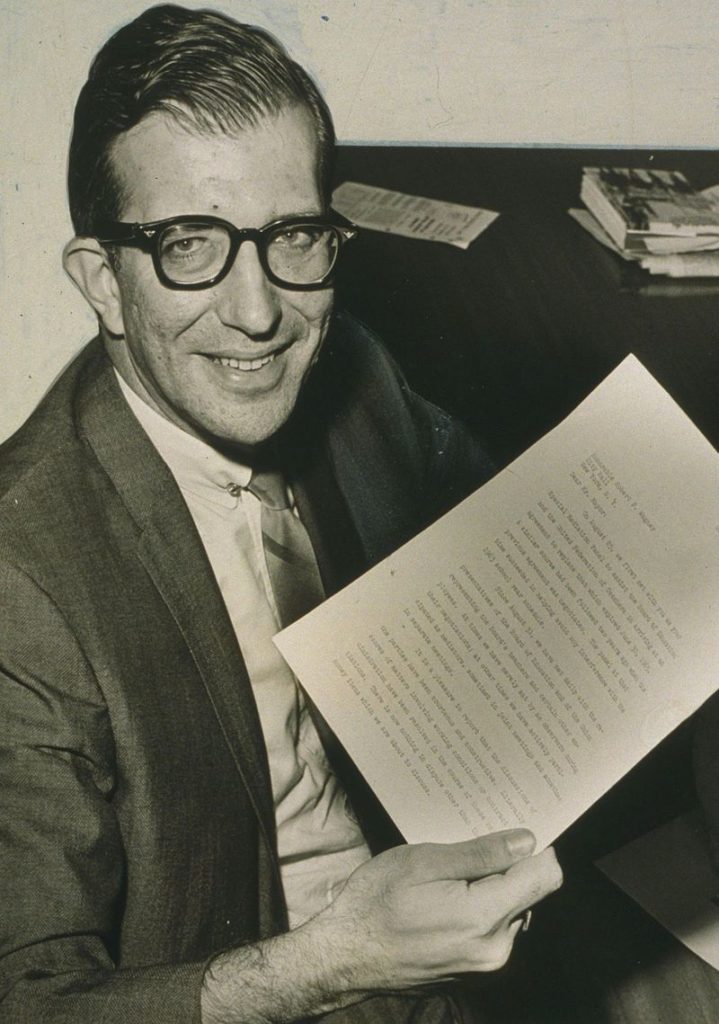

In 1989, Shanker (who died in 1997) was president of the American Federation of Teachers and arguably our nation’s most famous teachers union leader when he wrote:

“Business as usual in the public education system is going to put us out of business…It’s time to admit that public education operates like a planned economy, a bureaucratic system in which everybody’s role is spelled out in advance and there are few incentives for innovation and productivity. It’s no surprise that our school system doesn’t improve: It more resembles the communist economy than our own market economy…no law of nature says public schools have to be run like state-owned factories or bureaucracies.”

While Shanker’s words may seem bizarre, especially given the conservatism of today teacher union leaders, in the context of the 1980s and early ‘90s they weren’t that strange. The 1980s were the era of teacher empowerment and site-based decision making, at least rhetorically. The National Education Association (NEA), the nation’s largest teachers union, took the lead with several projects that explored giving teachers and principals more control over how their schools and classrooms operated.

I was teaching at St. Petersburg High School (SPHS) in the ‘80s when we joined the NEA’s Mastery-In-Learning Project, which was the country’s largest experiment in teacher empowerment and site-based decision making. After receiving training from NEA staff, we surveyed the school’s teachers, support personnel, and administrators to determine their improvement priorities, organized ourselves into committees around the most requested improvements, and went to work implementing those priorities. The biggest change we implemented was moving from a seven-period day to a block schedule in which classes met every other day for two periods.

We spent over a year preparing the faculty and staff for this change, including lots of training in how to use longer blocks of instructional time effectively. Block scheduling lasted about a year before divisions within the SPHS faculty killed it. Several of our more veteran teachers had instructional routines they’d been using for decades that they didn’t want to change. We then pulled back and tried smaller changes that did not impact the entire school, but the project deteriorated into lots of trivial debates.

I knew the initiative had failed when I sat through an hour-long meeting in which a committee debated whether to give teachers assigned parking spaces in the faculty parking lot. Some liked the idea of having their own parking space. Others who tended to be late every day feared the principal would be better able to identify the late arrivals.

By the late ‘80s, local and state teacher union staff were becoming increasingly hostile to the teacher empowerment movement because of the requests they were getting for contract waivers. School faculties were finding their hands tied by restrictive union contracts and were increasingly asking for relief from contract language, which raised red flags with the staff who negotiate and enforce those contracts.

I vividly remember being in a room with several dozen NEA staff in Kansas, all males, and being told that teachers needed to focus on their classrooms and not worry about other issues. “They don’t need power,” one older man said. “That’s why they pay us. It’s our job to take care of them.” The room reeked of institutional sexism (most teachers are women), but the union business model is a top-down, command and control system that abhors flexibility.

Despite these implementation problems, the NEA received lots of positive national media attention from its various teacher empowerment initiatives, and Shanker’s 1989 column was a response. Shanker’s union, the AFT, was competing with the NEA for members and publicity. Shanker often used his weekly New York Times advertorial columns to suggest the AFT was more innovative and progressive than the NEA. The AFT is much more decentralized than the NEA, which meant Shanker’s provocative ideas had little or no practical impact within the union, but the national media didn’t know that. Consequently, Shanker was able to portray the AFT as the more progressive teachers union, when in fact it wasn’t.

By the early 1990s, the teacher empowerment/site-based decision-making movement of the 1980s had run its course. We still believed in more decentralized decision making, but we needed a way to keep the focus on improving student learning. Hence, the emergence of the modern standards movement.

In 1991, under the leadership of Commissioner of Education Betty Castor and Gov. Lawton Chiles, both Democrats, Florida passed Blueprint 2000, which was legislation designed to shift more decision making power to district schools in exchange for holding these schools accountability for meeting various performance standards. AFT’s Florida chapter fiercely opposed Blueprint 2000, despite Shanker’s 1989 column supporting more decentralization, arguing that district schools simply needed lots more money. The NEA’s chapter strongly supported the Democrats’ legislation, arguing that more money would not generate better results unless schools had more control over how those funds were spent. Florida’s AFT and NEA unions merged in 2000. They now adhere to the AFT position that systemic improvements are not necessary. School districts just need more money.

Blueprint 2000 never worked as Commissioner Castor and Gov. Chiles envisioned. School districts opposed giving their schools any meaningful decision-making power, and local teachers unions generally refused to include more flexibility in their collective bargaining contracts. When Jeb Bush became governor in 1999, he and Republican legislators used the regulatory accountability tools that were spawned by Blueprint 2000 to coerce school districts into putting more resources into educating low-income and minority students. While this pressure led to some impressive learning gains, excessive regulatory control has exacerbated the similarities between how Florida’s public schools are managed and those Soviet-style management practices Shanker criticized.

Given Shanker’s role in crushing the efforts of minority communities in New York City to have more control over their local schools, his 1989 call for more decentralized decision making in public education seems disingenuous. He never made any significant efforts to put his anti-communism rhetoric into practice within public education.