A new study from the Urban Institute on college enrollment/completion rates of Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students represents both a triumph and a call for additional action. Let’s touch upon the triumph part first.

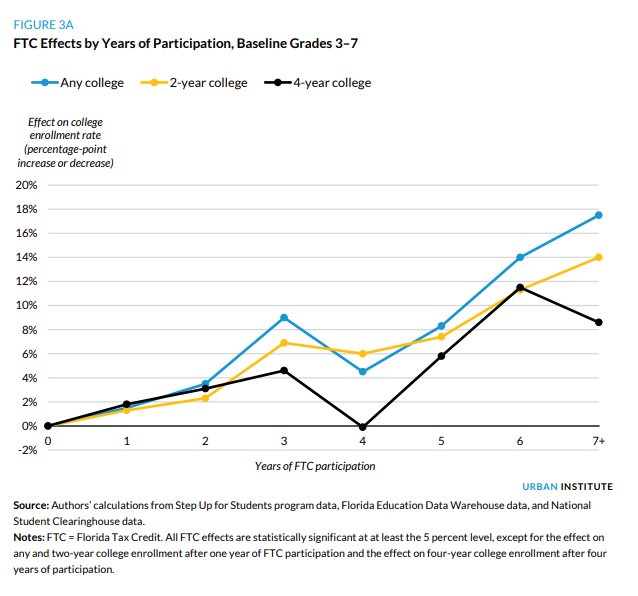

The analysis shows statistically significant benefits for students participating in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship in both college attendance and degree competition compared to a matched sample of similar Florida public school students. Moreover, the study finds that the longer students participate in the program, the greater the size of positive effect.

Some context makes these findings all the more impressive: The average size of the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship is less than $7000 on average while the state of Florida spent $10,145 per pupil in 2015-16. Increasing the return on K-12 investment is precisely what Florida needs, and what the tax-credit program delivers.

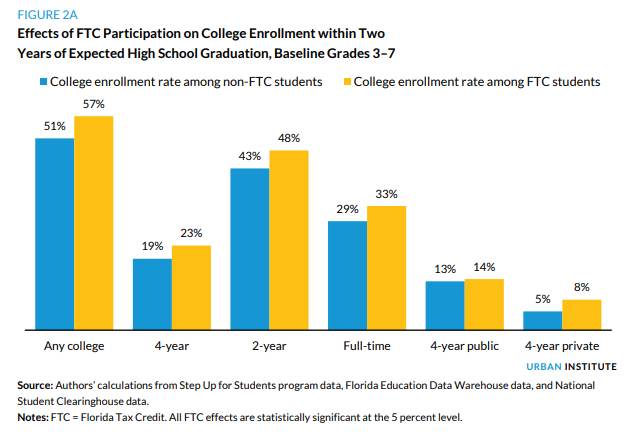

The Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program provides scholarships for low-income students to attend private schools. Florida is among those states with the highest degree competition rates in the country, and this includes very successful programs providing bonuses to public schools for students passing college credit by exam. We have reason to suspect, therefore, that the Florida “blue” columns in the Urban Institute chart above would rank competitively if we had similar data from the other 49 states. Nevertheless, the FTC students (“yellow” columns) show statistically significantly higher attendance rates across all attendance groups.

The progressively larger impact seen in the Urban Institute analysis sits comfortably with earlier random assignment studies of choice programs, which found modest but (crucially) cumulative year-by-year gains for choice students. Seeing significant long-term higher education benefits for disadvantaged students at a lower per-pupil cost represents an unambiguous triumph of policy innovation. This success should embolden further reform.

These results are great, but students need much more. Thus far, we only have scratched the surface of the potential to positively transform learning. It is vital to give families the opportunity to choose a good-fit school for their child, and there are a variety of benefits to such policies above and beyond those captured in the Urban Institute study. School, however, represents only part of the picture to learning, and what the country and Florida needs is a process to discover methods to substantially improve learning on a continual basis. In other words, American learning should constantly improve.

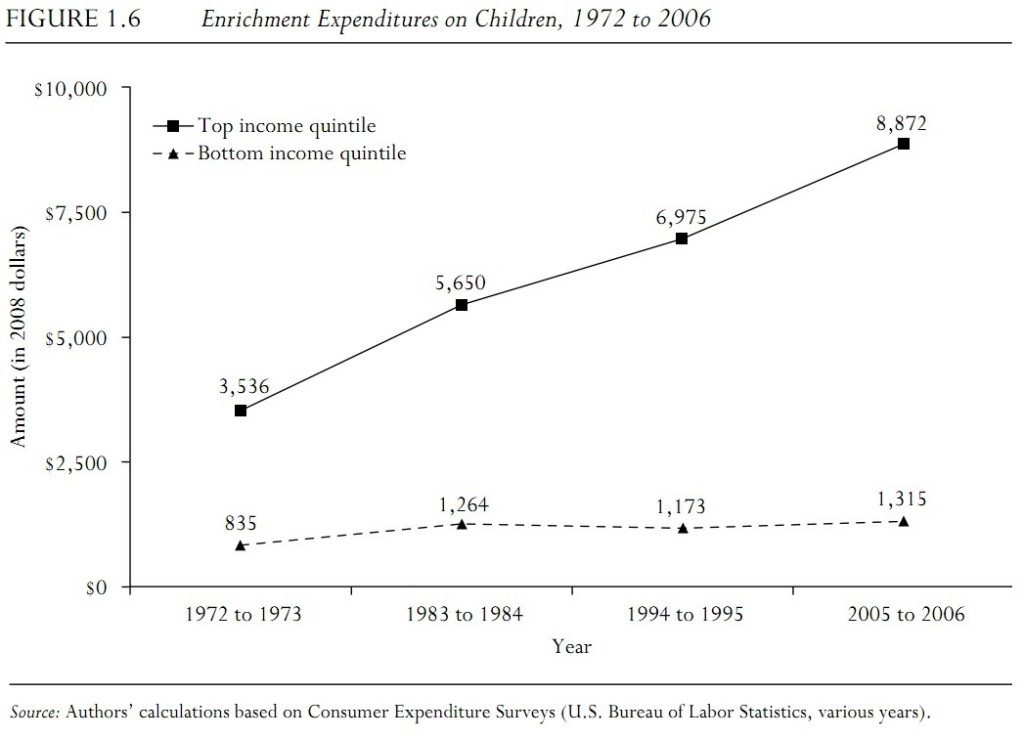

Status-quo defenders frequently lay the blame for the failings of public education at the feet of poverty. This school of thought struggles to explain why countries with far less money and far greater poverty manage to deliver a much higher bang for the education buck. Take a gander at the above chart and ask yourself: Just how much of the success in American learning can we attribute to our schools?

If history is any guide, we safely can conclude that a system of ZIP-code assigned schools governed by boards with visibility and turnout with few to no other choices is not likely to produce continual improvement. We’ve enjoyed some success with quasi-market mechanisms to allow educators to create alternative public schools and policies to allow select students to attend private schools. We should, however, view these policies as primitive prototypes in an evolutionary process.

In 2006, the New Commission on the Skills of the American Workforce, which included a bipartisan mix of the great and good including two former Secretaries of Education and an assortment of other grandees concluded, “We’ve squeezed everything we can out of a system that was designed a century ago. We’ve not only put in lots more money and not gotten significantly better results, we’ve also tried every program we can think of and not gotten significantly better results at scale. This is the sign of a system that has reached its limits.” Commissioner Jack Jennings told the Christian Science Monitor: “I think we’ve tried to do what we can to improve American schools within the current context. Now we need to think much more daringly.”

Some 13 years later, these assessments still ring true – and not just for public schools. School vouchers and charter schools were radical and state-of-the-art technologies in 1990 and 1991, respectively. We need new policies, new schools, new school models and more choice among methods of education in addition to schools and policies that will empower teachers to realize their own visions of a high quality education. Emboldened by the success of our prototype policies, we do indeed need to think much more daringly.

[…] research from the Urban Institute, for example, shows low-income students participating in Florida’s tax-credit scholarship program, the country’s largest, have higher college enrollment and completion rates than their […]