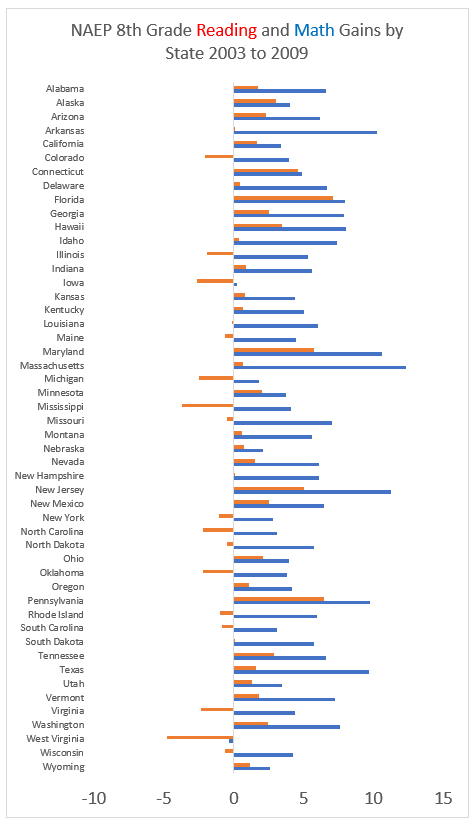

The aughts were a time of K-12 academic improvement. For some states, including Florida, that improvement started earlier, but included the era illustrated in this chart.

The aughts were a time of K-12 academic improvement. For some states, including Florida, that improvement started earlier, but included the era illustrated in this chart.

All states began participating in NAEP exams in 2003. Most states experienced a pronounced improvement in eighth-grade reading and eighth-grade math from 2003 to 2009. On these tests, 10 points equals approximately one grade level’s worth of average progress.

As you can see, there are far more bars going in a positive direction in the first chart and relatively few going in a negative direction between 2003 and 2009. Now let’s examine the same sort of chart between 2009 and 2019.

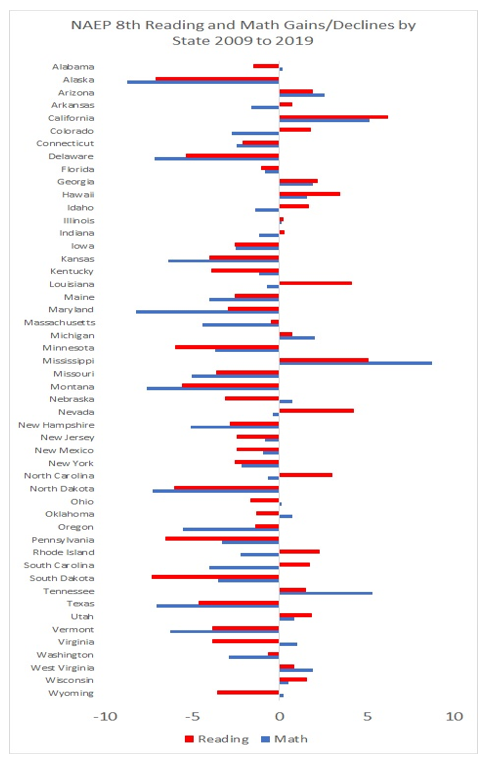

Things went badly after 2009 in most states. Some broad theories readily come to mind but are weaker than they might seem.

Most states adopted the Common Core standards after 2009, for instance. Prominent analysts of the center right and left have studied the impact of Common Core on academic achievement and have reached a common conclusion: not much positive or negative impact. Look at Texas on both charts; positive experience in 2003 to 2009, deeply negative experience from 2009 to 2019. Texas never adopted Common Core.

Obviously, lots of states that did adopt also had bad decades, but Mississippi had the biggest 2009 to 2019 gains. Judged against lofty promises of improvement, the Common Core project clearly fell flat at a high cost in terms of political and financial capital. That is very different than saying they worsened outcomes, but it’s still very bad.

It was the economy! My friend Mike Petrilli has been exploring the theory that the Great Recession is a driver of decline in NAEP performance. Texas, again, is a fly in this ointment.

The Texas economy got off light in the Great Recession and boomed economically for much of the 2009 to 2019 period, but Texas scores worsened statewide. The so-called “Sand States” – Arizona, California, Florida and Nevada – were the hardest hit in the housing downturn, but they all had a much better decade driving academic improvement than Texas.

Per-pupil spending has been increasing since fourth-graders of 2019 took the NAEP, and for most of the time eighth-graders have been in school. We should hope that Mike is wrong about this given that the country is overdue for a recession by historical standards.

Sandy Kress makes the case that the blame lies in the Obama administration’s decision to let the pressure off test-based accountability. The trends certainly show something went south after 2009, and Sandy may be right. It’s worth considering whether something had to give with the 100 percent-ish proficiency on a deadline NCLB requirement.

Before President Obama took office, I had feared states might simply drop their passing thresholds if the federal government stuck to its guns. Moreover, the Common Core project coupled with teacher evaluation can be seen as a doubling down on high-stakes testing strategies, one that radicalized opponents countered in a variety of (largely predictable) ways.

So, what to make of all of this?

Providing academic transparency to parents, taxpayers and policymakers remains vital, but it’s clear the public is not on board for heavy-handed, top-down testing mandates. We live in a democracy, and the demos is not enamored with the idea of closing schools based on test scores and firing teachers based on test scores, and are sick of the amount of test prep going on in school these days. If you doubt any of that, feel free to focus-group it, or alternatively go outside and talk to normal people.

In many states, much of the low-hanging academic improvement fruit of the NCLB era has been reversed post 2009. Sun Tzu wrote that “a victorious general wins and then seeks battle whereas a defeated army seeks battle and then seeks victory.” It’s clear which of these two profiles education reformers more closely resemble today.

A good first step to recovery would be to focus on policies that have the prospect of developing supportive constituencies rather than annoying the public. Those who adhere to the status quo have the upper hand in most states even without antagonizing the public.

Texas standards had the same effect of dislocating classrooms from their optimal points of lesson delivery. Common Core was devastating. The ECLS clearly showed high performance classrooms to be maximally differentiated. Common Core and standards generally minimize differentiation and even for minimally differentiated classes force those classes away from their optimal single point of lesson delivery. Should students who don’t know how to add be studying fraction procedures? We paid a horrible price for Race To The Top