Trips to the cineplex are important holiday rituals in the Ladner clan, and Midway was on the viewing list this year. I enjoyed it. Looper issued a video with several scenes you might suspect were Hollywood embellishments. But nope, they actually happened.

The Battle of Midway is a helpful reminder about many admirable aspects of American society. George Orwell said that to understand London, one had to visit Paris. Imperial Japan is a good stand-in for our un-America, which allows us to understand ourselves better.

Japan of the 1930s was a monarchy run by rival elites of the Army and Navy. The film does a decent job of portraying this rivalry and hints at the precipitating cause of the Pearl Harbor attack. Japan imported most of its oil from the United States at the time. Horrified by atrocities in Japan’s empire building in China, the United States passed an embargo on the sale of oil to Japan. The Japanese elite decided to secure new sources for oil but understood the need to knock out the American fleet at Pearl Harbor to do so.

All of this reminds me of a quote from Matt Ridley’s book, “The Evolution of Everything: How New Ideas Emerge.”

The elite gets things wrong, says Douglas Carswell in “The End of Politics and the Birth of iDemocracy,” because they endlessly seek to govern by design in a world that is best organized spontaneously from below. Public policy failures stem from planners’ excessive faith in deliberate design. They constantly underrate the merits of spontaneous, organic arrangement, and fail to recognize that the best plan is often not to have one.

Elitist societies, like the pre-Civil War American South, are prone to making rash decisions to suit the needs of their elite. Japan’s elite got the Pearl Harbor attack very, very wrong, and it cost their country dearly. Japan had employed similar tactics successfully against Russia earlier in the century, but the United States was no sclerotic Czarist Russia.

Despite putting a priority on Europe, the USA was far more than Japan would ever have been able to handle. At one point, for instance, the United States was producing a new state-of-the-art aircraft carrier per month. Japan brought six such carriers to attack Pearl Harbor and lost four of them at Midway.

The pilots who carried out the Pearl Harbor attack were the best trained in the world. Their planes were superior to ours at the outset. The elitism of pilot training, however, represented a severe weakness. Many of the pilots who carried out the Pearl Harbor attack died in the battle of Midway. Given that pilot training was akin to graduating from Harvard Law in the Japanese system, this was a huge problem.

Where did the United States get enough pilots to crank out a new fleet carrier every month? It went something like “Hey Tommy, you’re a bright kid and good in a fight. How would you like to become a fighter pilot?”

American planes improved in quality and quantity. Admiral Yamamoto, the architect of the Pearl Harbor attack, realized the scale of their folly after the attack, stating, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.”

The Japanese elite had not just underestimated American industrial capacity and human capital; they also underestimated American ingenuity. “Midway” accurately portrays the crucial role played by American codebreakers in the pivotal Midway battle.

Yamamoto aimed to draw the remaining American aircraft carriers into a trap by attacking Midway Island. Admiral Nimitz learned of their plans and instead had our remaining carriers lying in wait to destroy the four Japanese carriers. A group of Navy musicians proved crucial to the codebreaking effort.

A key to American success in World War II was making good use of talent, whether in the form of repurposed musicians or Rosie the Riveter back in the factories. We were much better at this than Imperial Japan, but not as good, either then or now, as we could or should be.

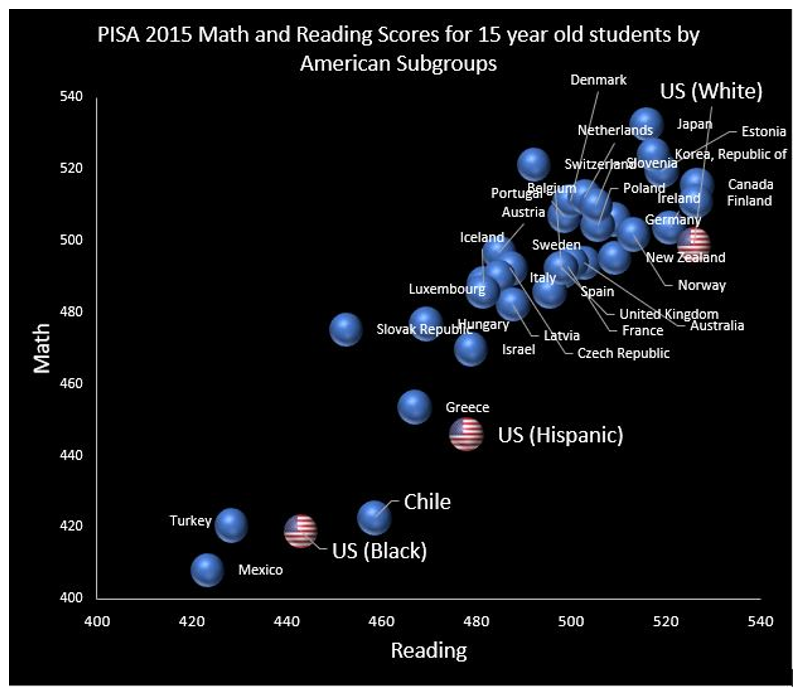

Today, state, national and international testing data show that talent development is not normally distributed in the United States. White students in America sit comfortably among the ranks of the top European and Asian education systems, while American black and Hispanic students score closer to the averages of countries that expend a fraction of our financial effort:

Our ancestors weren’t afraid of foreign competition. They made the foreign competition afraid of us. If we want to “make America great again,” we need to expand the opportunity for everyone to flourish in a growing and innovative society.

Equipping children with literacy and numeracy is a key component of mobility. The performance of our education system is a major impediment to such an aspiration, and in fact, may have us trending toward a detrimental elitism of our own.