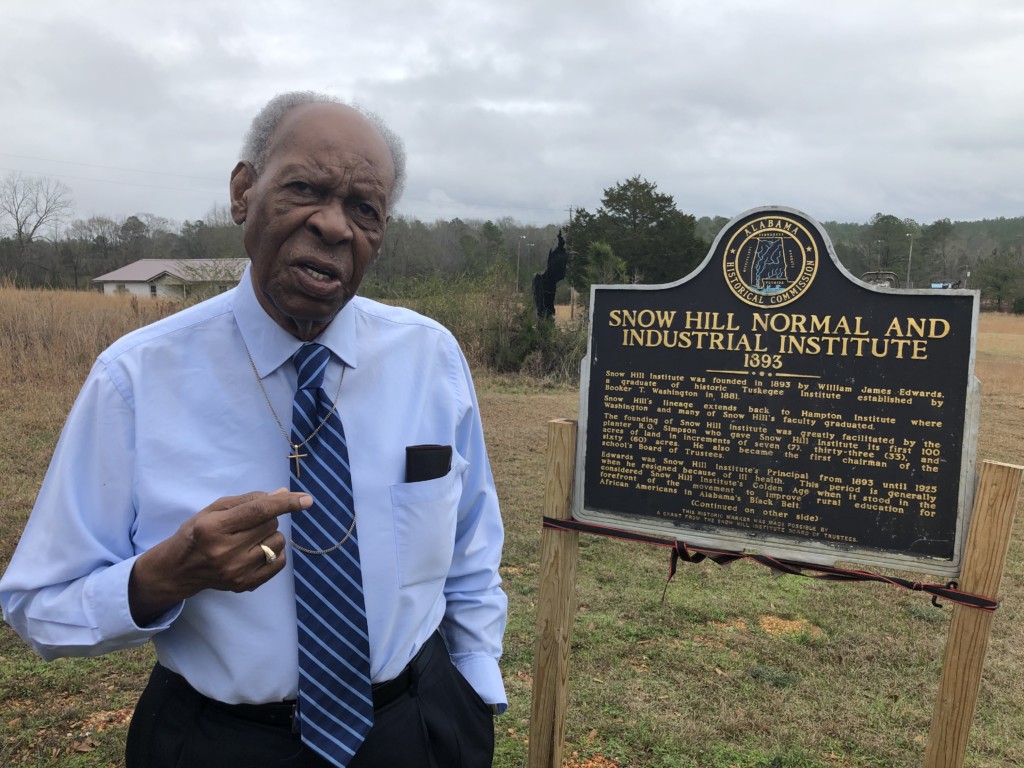

SNOW HILL, Ala. – There isn’t much left of Snow Hill Institute, an all-black school that once drew thousands of students to this backwoods speck from as far as Mobile and New Orleans. A half-dozen empty buildings, red brick and rotting wood-frame, conjure a century’s worth of ghosts.

H.K. Matthews, class of ’47, unfolds himself from a Camry and is instantly possessed by memories of … a garlic-loving ag teacher named Mr. Brooks. One time, with Mr. Brooks out of the classroom, Matthews and another student started wrestling, inadvertently spilling a bottle of ink on Mr. Brooks’ papers. When Mr. Brooks returned, he whipped them with a leather strap, then, later that day, whipped them twice more.

“I was 17,” Matthews laughed. “Can you imagine a teacher whipping a 17-year-old today?”

Hard to imagine, too, the reign of terror that served as backdrop.

In the 50 years before Matthews was born in 1928, white Alabamians lynched 300 of their black neighbors. When Matthews was 6 years old, a white mob from Florida broke into the jail in Brewton, Ala. – where Matthews now lives – to kidnap and kill Claude Neal, a black man accused of raping and killing a white woman. By the time Matthews and his classmate knocked over that ink bottle, 14 more black men had been lynched in Alabama.

Matthews’ grandmother, who raised him, tried her best to prepare him for this world. So did the school. Sometimes that meant setting high expectations with a strap. Sometimes that meant counseling patience.

“Life is like a revolving wheel,” his grandmother, a teacher, told H.K. on a segregated bus, the first time racism made him cry. “Those who are on top today will be on the bottom tomorrow.”

She and the school drilled the same lessons deep. Faith. Education. Resilience. Self-reliance.

“Whatever I am today,” Matthews said, “my grandmother – and this school – are the responsible parties.”

***

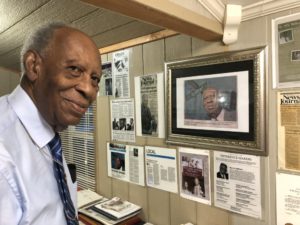

Ramble a half-hour north of the Florida line, past stalky remnants of cotton fields and ramshackle sheds with fresh okra signs. You’ll find the retired Rev. H.K. Matthews in a modest home of trim brown brick. The sign on the front door says, “Southern Charm.” The sign in the yard says, “WE BACK THE FAMILIES OF THE INNOCENT WHO WERE KILLED BY THE BLUE.” It’s a reference to police brutality.

Matthews’ life reads like a Deep South Odyssey. In the 1960s and ‘70s, he was “the Martin Luther King of Pensacola,” an uncompromising leader of both the local NAACP and Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was beaten at Selma. Arrested nearly 40 times. Twice, he escaped Klansmen waiting to kill him in motel rooms.

Matthews settled in Pensacola after fighting for the Army in Korea. For two decades, he led campaign after campaign to dismantle Jim Crow on the “Redneck Riviera.” He pushed for voting rights, desegregation of lunch counters, better schools for black students. At one point, to get Southern Bell to change its racist hiring practices, Matthews urged every black customer in Pensacola to pay their bills in person – and in pennies. Lickety-split, the company became a little more color blind.

These days, Matthews reaches for his cane if he has to stand too long. But he is still tall, spry, focused, engaged. When he tells any of a thousand stories about being an “agitator,” a smile crinkles the corners of his eyes. When he ends them, he likes to say, “What a ride it’s been!”

The ride continues.

Earlier this month, Matthews joined 150 other black and Hispanic pastors in the Florida Capitol to condemn lawmakers who’d been bullying corporate donors into abandoning the nation’s largest school choice scholarship program. (That program is administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.) “It’s not social justice,” Matthews said, in comments picked up by national news outlets, “to throw thousands of low-income, mostly black and Hispanic students under the bus.” Three days later, the biggest donor to leave announced it was re-joining.

This wasn’t the first time Matthews spoke out at a critical moment. Ten years ago, 5,000 people marched for school choice in Florida’s capital city – at that time, the biggest choice rally in history. What followed was bipartisan support for legislation that made Florida a national leader in private school choice.

Matthews walked in the front row. And given his own experience with public education in America, it’s no wonder.

***

Snow Hill Institute was founded as a private school in 1893, by Tuskegee Institute graduate William J. Edwards. Its arc parallels the rise of the Rosenwald schools, the 5,000 quasi-public schools, seeded by money from philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, that served as a segregation-era bridge to better schools for black students in the South.

As a condition of his contribution, Rosenwald required black communities to raise the lion’s share of funds for the new schools, and to technically turn the schools over to white public-school districts. The schools were separate by race, unequal in funding. But many were built to cutting-edge architectural designs. They were orders of magnitude better than the sad shacks that passed as public schools for black children. And in an ironic twist, they also often remained in the black communities’ control.

Black teachers. Black principals. Black community decisions over hiring, curriculum, discipline. It’s not hard to find, among Rosenwald alum, a belief that this was a golden age for black education in America.

Rosenwald contributed to Snow Hill Institute. But Edwards (great-grandfather of film director Spike Lee) secured donations from other white Northerners who were the progressives of their day. Within 25 years, what started in a rented log cabin with one teacher, three pupils and 50 cents in savings had become 24 buildings on 1,940 acres, with 400 students and a property value of $125,000, according to a book by Edwards, “Twenty-Five Years in the Black Belt.” Graduates dispersed throughout the South, spreading the gospel of self-determination.

Edwards described the spillover effects in Snow Hill.

Twenty-five years ago the people in the neighborhood of the school did not own more than ten acres of land, while today they own more than twenty thousand acres. Twenty-five years ago the one-room log cabin was the rule, today it is the exception. Twenty-five years ago the majority of the farmers were in heavy debt and mortgaged their crops, today many of the farmers now have bank accounts, while a few years ago they did not know what a bank account was.

After Snow Hill Institute became public in 1924, it continued to educate thousands of students, including Matthews. But in 1973, it closed, due to court-ordered desegregation.

Brown v. Board rightfully ended “separate but equal” in public schools. But for many black communities, it ended community control, too. Black teachers lost their jobs. Black students were sent to white schools that were indifferent, if not hostile. Matthews said the tradeoffs shouldn’t be sugar coated.

“How much was lost to assimilation?” he said on the abandoned campus, as crows cawed in the chill.

“All of it.”

***

The team name for Escambia High was “The Rebels.” The band played “Dixie.” By 1972, the black students who now made up 10 percent of this once-all-white public school in Pensacola were done with the relentless hostility. White students waved Confederate flags. Showed up in Klan hoods. Spray-painted “KKK” on walls. Black leaders took their concerns to the school board, but the board was not responsive.

“Their mood was worse than what we had encountered with other institutions,” Matthews wrote in his 2007 autobiography, “Victory After The Fall,” co-authored with history professor Michael Butler. “They were much more hostile, bitter, and closed to compromise … ”

As fall unfolded, fights broke out, students got arrested, white lawmakers stirred the pot. One of them said to others in a Capitol hallway, in words reported on TV news, “Those n****** make me so mad … If I had anything to do with it, I would get a shotgun – no, a submachine gun – and mow them down.”

In December, the district closed the school because of racial unrest. The NAACP and SCLC followed with a list of demands. If the board didn’t act, the groups said, the community would boycott the schools. Right after New Year’s, that’s what it did.

But black students didn’t stay home.

***

Fewer students attending public schools meant less money for the district and its white employees – and more leverage for progress, Matthews reasoned. At the same time, black parents would not tolerate their children being out of class.

So Matthews organized “freedom schools.”

They were inspired by the schools civil rights activists created during “Freedom Summer” in Mississippi. The SCLC in Pensacola turned to black churches to house them, to retired black teachers for instruction. It worked. Hundreds of black students attended classes in core subjects, with black contributions in history and literature infused into the curriculum. The newspaper blasted the schools. A state senator called for the arrest of black parents (for allegedly abetting truancy). But parents kept dropping their kids off.

The boycott continued until a judge issued a temporary injunction against use of the Confederate flag and “Rebel” nickname at Escambia High. The freedom schools in Pensacola closed. But Matthews started them in three other North Florida towns where black communities battled white school districts.

Years before “school choice” became a thing, Matthews was all in.

***

In December 1974, a white sheriff’s deputy in Pensacola chased down a black motorist, Wendel Blackwell, then shot and killed him from three feet away. According to Matthews’ autobiography, a black woman had been in the car with Blackwell. The deputy had been having an affair with her. A few days later, she was found dead beneath a highway overpass. The deputy was never suspended. The state attorney concluded he acted in self-defense.

Matthews led the protests. But as anger mounted, the sheriff’s department arrested him on a bogus charge of extortion, for allegedly trying to force the sheriff to fire the deputy under threat of violence. An all-white jury found Matthews guilty. He was sentenced to five years in prison. After 63 days, one Florida governor, Reuben Askew, commuted his sentence. Another, Bob Graham, pardoned him. But in the aftermath, Matthews could no longer find work in Pensacola.

“Blackballed?” I asked. “Whiteballed,” he said.

Matthews returned to Alabama. For 40 years, he served as pastor of Zion Fountain AME Zion Church in Brewton. But he never stopped getting into “good trouble.”

In 2015, he was among many speakers – but the one with the most notoriety – who urged the county commission in Pensacola to cease flying the Confederate flag over government property. On his way home, a truck with Confederate flags flapping began tailing his Altima. It switched lanes when he switched lanes. It followed him into Alabama. Rounding a familiar curve with a side road, Matthews, then 87 years young, cut the lights, turned sharp and checked the rear view. “The truck kept on,” he said.

“What a ride it’s been!”

***

A half-century after integration, 10 schools on Florida’s list of “persistently low-performing” schools are in Pensacola. All 10 are predominantly students of color. Eight are majority black. Decade after decade, community after community, the same sick story plays like a broken record.

Back at Snow Hill, Matthews shook his head. In the darkest of times, black communities scratched out ways to build schools that worked for their children. Today, they have more tools than ever to build more, better, faster.

“Why not another Snow Hill Institute?” Matthews said.

“Why not 1,000 of them?”

In case it isn’t clear, Matthews wasn’t asking.