Like most schools that were shuttered by the COVID-19 virus, North Florida School of Special Education in Jacksonville had to sprint to set up a distance learning program for students suddenly confined to their homes.

For Sally Hazelip, the head of NFSSE, it was a longer race that taught her how to navigate unfamiliar education territory.

“I just ran a marathon in October, and your mental strength in a marathon is almost as important as your physical strength, she said. “That’s what this is like now: Just put one foot in front of the other and push through it.”

While adapting on the fly to the virtual classroom has been disruptive to educators, students and parents in public and private schools, the transition has been particularly challenging to NFSSE. It has 250 students with intellectual and developmental differences, such as Down syndrome, autism, fetal alcohol syndrome, and traumatic brain injury. Most are between the ages of 6 and 22 (including 26 students on the Gardiner Scholarship, which is administered by Step Up For Students, the host of this blog), while 65 post-graduates ages 22 and up receive vocational training in micro-enterprises.

Switching them to online lessons overnight yanked everyone out of their comfort zones.

“The fear of the unknown can sometimes be daunting,” Hazelip said, “but my staff has risen to the occasion in so many unique ways.”

Parents also wondered how they would handle the additional responsibilities.

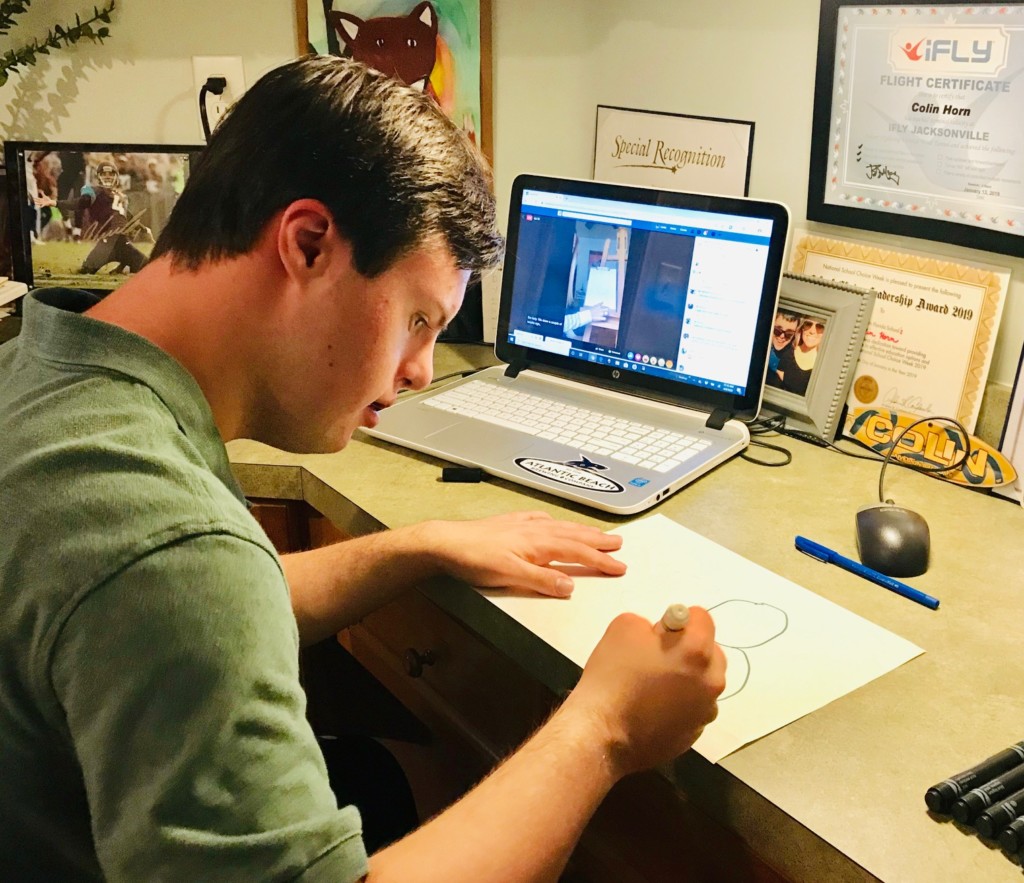

For Linda Horn, whose son Colin, 18, has Down syndrome, the change forced her to recall her days homeschooling her child when the family lived in Seattle.

“I had to personally change my mindset – I had to accept it,” Horn said. “I had to be a better mother and teacher for Colin. I had to be the adult in room. I needed to show Colin everything was calm and routine.”

Cathy Roberts suddenly had three children learning at home: Christian, 17, who has Down syndrome and attends NFSSE; a 16-year-old son with ADHD who attends another private school for students with learning differences; and a 17-year-old daughter who is typical and attends a Catholic school.

“Structure for our kids is key,” Roberts said. “I had to sit down with Christian and explain the virus to him. Initially he was upset. He wanted to go to school. I put up a calendar so he can go to it every day and see his schedule. I have had to become more structured. It’s been a change for all of us.”

Thankfully, several online curricula – Unique Learning Learning System, i-Ready, TouchMath – already were being employed on Smartboards in NFSSE classrooms, so teachers and students were familiar with them. That helped facilitate the academic side of the equation.

What sets NFSSE apart from other schools, though, is what happens outside the classroom.

The school offers several unique hands-on learning opportunities that stimulate intellectual and emotional development and prepare students for independent living. These include Berry Good Farms, an urban organic farm that grows fruits, vegetables and herbs; a culinary arts program where students prepare what the farm grows; therapeutic and recreational horseback riding; and cross-fit training. The school operates a food truck that goes out regularly into the community. Its Barkin’ Biscuits program uses fresh ingredients from the farm to make dog biscuits sold on the retail market.

NFSSE also has reverse-inclusion clubs in which typical students from outside the school participate in extracurricular activities and vocational training programs. And in January, the school opened its crown jewel, a $10 million state-of-the-art campus expansion whose amenities include a fine-arts center, individual rooms for sensory, physical, speech and occupational therapies, and a physical education complex with a gym and locker rooms.

“Academics are incredibly important,” Hazelip said, “but those hands-on activities take them to a different place and keep them engaged.”

Now those activities are on hold, awaiting the all-clear signal to return on the public health front. With it goes a huge part of what makes NFSSE special – elements that are difficult, if not impossible, to replicate remotely.

It’s like limiting Superman to one superpower. The school and its families have been up to the challenge, though.

“I think families with kids with special needs are really resilient,” said Hazelip, whose son Collin, 25, has Down syndrome and is a graduate of NFSSE. “There are so many unknowns. You don’t ever feel like you have all the answers. Part of it is just taking things one day at a time, and to look for creative ways of connecting with your child.”

From the start, teachers have been in close contact with parents and students every step of the way. The school has supplied laptops to families who lacked them. They are using Zoom to conduct live, interactive lessons in core subjects. Students submit assignments at their own pace.

“Zoom has been a godsend,” Roberts said.

Resource teachers use Facebook Live and the school’s private YouTube channel to hold daily art, music, PE, gardening and yoga classes, as well as story time. Berry Good Farms teachers post video cooking classes for students to follow. The equine teacher shot a video showing how she feeds the horses.

On April 3, the school even held its monthly scheduled student and faculty assembly, only this one was recorded in advance and posted online. It included special guest Josh Lambo, place-kicker for the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars, who read the Dr. Seuss book “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!” Over 150 people watched it live.

Virtual learning is not the same as being out in the greenhouse or the stables, but it maintains the connection between teacher and student, and keeps the kids on a routine that for many is vital to their intellectual and emotional development.

“North Florida prepared [Christian] well for this,” Roberts said. “They already do a lot of work on computers, that part was easy for him. He has such a tight-knit bond with his teachers, being able to see them every day has made a difference.”

Linda Horn has tried to fill the additional time at home with Colin with life skills as he prepares to enter the school’s transition program next year.

“Independent living skills are important,” she said. “So we work on doing the laundry, cooking skills, getting lunch ready and working on dinner.”

She and her son also try to get out in the community as much as possible in the era of the coronavirus.

“I make it a point to stop and say, ‘Look at the plants here’,” she said. “I really try to incorporate what he’s learned. We’re going to go to Lowe’s and buy a tree and plant on Earth Day.”

Hazelip says this unplanned journey into distance learning can be characterized by two words: “resiliency” and “connection.”

“The biggest positive out of this ordeal is we’re one big family,” she said. “That support has given them strength to get through this.”