Recently, I watched Liberty: the American Revolution. The documentary includes a dramatization of letters Abigail Adams wrote to her sister while her husband served as United States ambassador to Great Britain.

Recently, I watched Liberty: the American Revolution. The documentary includes a dramatization of letters Abigail Adams wrote to her sister while her husband served as United States ambassador to Great Britain.

Abigail was less than impressed with “his Britannic majesty” and the other members of the British royal family, a family she noted to be “inclined to corpulence.” She observed that the English boasted of the beauty of the English princess, but it took more than a tiara to impress Abigail Adams.

“Your simple American girl is much prettier,” she noted, concluding, “There is a servility of manners here, a distinction between nobility and common citizens, which happily is foreign to Americans.”

Abigail’s lack of deference and her inclination to judge beauty by her own standards came to mind when I saw a new ranking of state charter school laws. Back in 2018, I offered a light-hearted nudge to my friends within the national charter school organizations with a post titled It’s Time for Technocratic Beauty Pageant Charter Rankings to End.

The basic point I attempted to make is that the charter school movement has fallen into the habit of passing charter school laws that haven’t produced many actual charter schools. Ranking charter-lite charter laws highly in ranking exercises seems even more dubious. Alas, I failed to prove persuasive as the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools released a new ranking of charter school laws last week, again judging laws against a model bill.

Stanford University’s Opportunity Project, however, has created a new tool that might help illustrate the point, so I’ll try again.

Stanford University’s Opportunity Project, however, has created a new tool that might help illustrate the point, so I’ll try again.

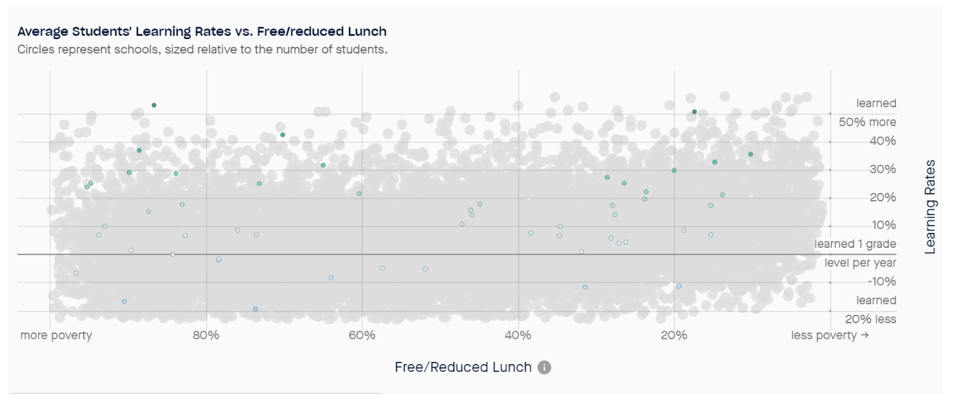

The chart above is drawn directly from the Opportunity Project’s data explorer and shows the academic growth scores for the charter schools in the state of Indiana. Indiana’s charter school law has placed first multiple years in a row in both the National Alliance and National Association of Charter School Authorizers (NACSA) rankings.

In these charts, green dots denote charter schools with above average rates of academic growth, blue dots below average academic growth. The grey dots in the background are the shadows of every other school in the country.

Academic growth isn’t the only criterion for judging schools, let alone a perfect one. New schools full of students who just transferred in, for instance, might be at a disadvantage; this would apply especially to youngish charters. Some of these schools also are likely alternative schools doing dropout recovery. With those caveats in mind, let’s proceed.

So, what to make of the Indiana charter sector’s outcomes?

There certainly are some high performing schools – four schools with a rate of academic growth 20% or more higher than the national average. Note, however, that an equal number have rates 20% below the national average. Counting the dots in Indiana reveals 21 high growth green dots, 22 lower growth blue dots, and one school right on the national average.

Like Abigail Adams, suffering through hours of Britannic court pomp, color me less than overwhelmed.

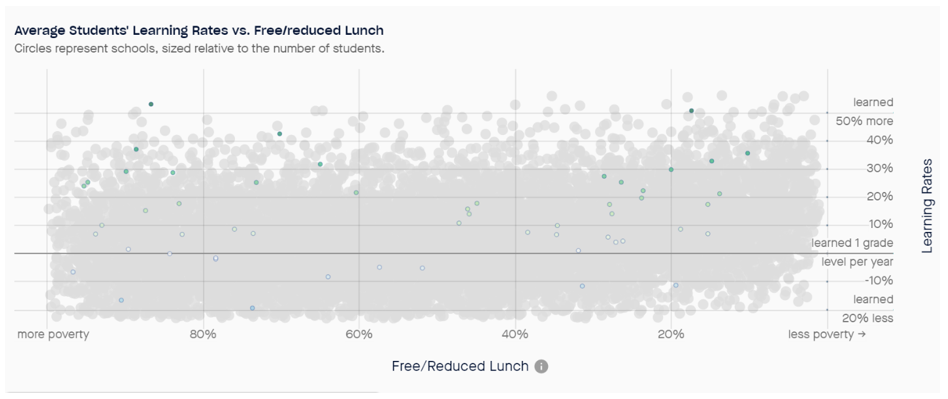

Next, let’s look at Indiana’s neighbor, Wisconsin. Wisconsin ranks 39th in the National Alliance rankings, which is near the bottom, as there only are 45 states with laws).

Next, let’s look at Indiana’s neighbor, Wisconsin. Wisconsin ranks 39th in the National Alliance rankings, which is near the bottom, as there only are 45 states with laws).

Wisconsin has a smaller population than Indiana but more charter schools. Wisconsin has five times as many charter schools showing academic growth 20% or more higher than the national average than Indiana. Wisconsin, moreover, has zero charter schools with a rate 20% below the national average.

Call me crazy – it’s been too long since anyone has – but by my way of thinking, Wisconsin has a better charter law than Indiana because it has created more high-quality opportunities for students.

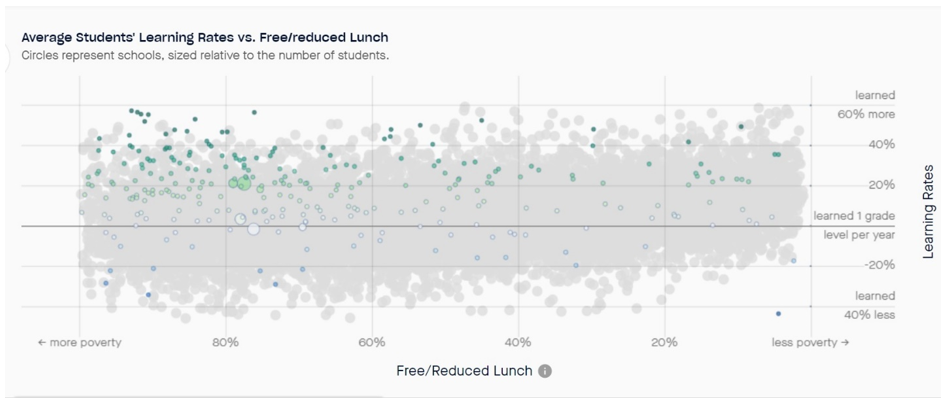

Now imagine you are working on charter schools in Texas, which came in 29th in the National Alliance ranking. Texas is a much larger state than Indiana, but note the ratio of dark-green schools to dark-blue dots in the Texas chart and compare it to the Indiana chart above.

Now imagine you are working on charter schools in Texas, which came in 29th in the National Alliance ranking. Texas is a much larger state than Indiana, but note the ratio of dark-green schools to dark-blue dots in the Texas chart and compare it to the Indiana chart above.

How much servility of manners would we expect Texans to show towards the Indiana law? Texas appears to have approximately three times more charters with rates of academic growth 20% higher than the national average than Indiana has in total charter schools, after all.

In my opinion, we ought to judge the beauty of charter laws not by their adherence to a model, but rather by their outcomes. If the model law continues to coronate a law with a notable lack of seats, schools or academic growth, the tiara raises more questions about the model than it bestows glory.