Back in 2015, I studied Census forecasts about predicted looming increases in state elderly and youth populations. Based on those forecasts, it was easy to see trouble ahead.

Six years later, it’s obvious that trouble did indeed arrive, in some cases as expected and in others, in a different form.

These grim forecasts remain on track, but an unforeseen “Baby Bust” and a global pandemic threw in some unexpected curves. The 2020s were always going to be a challenging decade for American K-12, and the chaotic opening to the decade should not overly distract us from understanding the bigger picture issues.

First off, there are the short-run issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic:

Public school enrollment fell during the 2020-21 school year. Parents around the country kept their young children out of kindergarten. This fall, school may have a larger-than-average kindergarten cohort as students return and a smaller-than-average first-grade cohort.

Schools could accommodate this situation in part by shifting first-grade teachers into kindergarten assignments. This likely will happen in many places, but then again, signs indicate parents may have other ideas. Denver Public Schools, for example announced that applications for pre-kindergarten for fall 2021 have declined by 20%v.

Although it’s too early to get a firm picture on the data, many school systems may be headed toward a second consecutive year of declining kindergarten enrollment. COVID-19 vaccines have not been approved for use in young children. Although research indicates that the flu is literally deadlier to young people than COVID-19 and that school staff has had access to vaccines, many people remain concerned. As many as one-quarter of American parents have indicated they will keep their children home this fall.

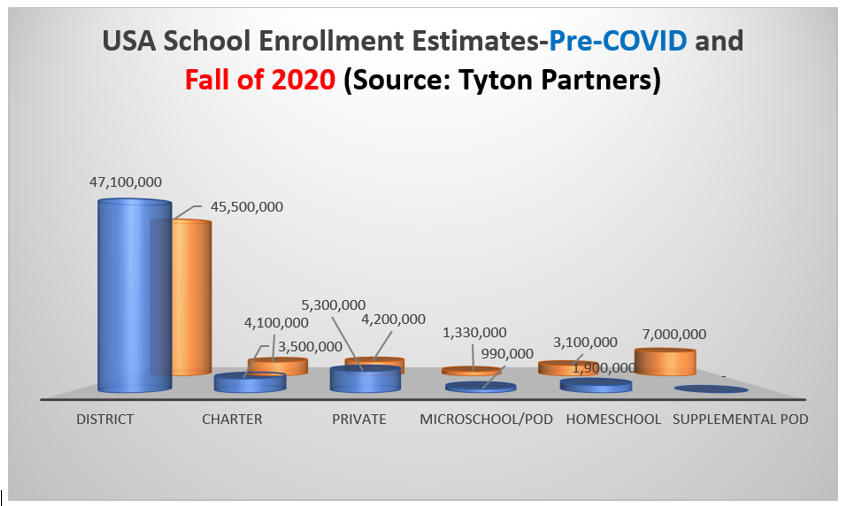

Tyton Partners, an advisory firm serving clients in the education, information and media markets arenas, performed a panel study of enrollment decisions and education spending of a panel of parents last fall. Based on parent response, the firm estimated trends illustrated in the chart above for fall 2020. The closer you study these trends, the more dramatic they seem; large increases in home-schooling, charter school attendance and micro-schools.

Nationally, charter schools took more than a decade and a half to reach the same 1.3 million student mark reached by full-time micro-school students last fall.

Almost out of thin air, 7-million students, by Tyton’s estimate, attended supplemental pods last fall. These students remained enrolled in a pre-existing school through digital learning arrangements, but participated in small “pandemic pod” gatherings for socialization and custodial care.

Scattered formative assessment data from pods during fall 2020 have been released, and the news is academically encouraging.

An investigation of student engagement in Chicago Public Schools with distance learning, for instance, found that one-quarter of students failed to log on once during the week studied. Students “enrolled” in a system continued to generate resources for that system, but whether they actually engaged in any learning is an entirely different question.

The longer-term age demography challenge involves an ever-growing cohort of aged retirees and funding imbalances in retiree entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare. At any given time, working aged people carry the primary financial burden of providing the resources to pay for the education of the young and the retirement of the elderly.

Much of the working-age population of the later 2020s, 2030s and 2040s just took an impromptu break from schooling.

The ability of American policymakers to sustain the social welfare state always has been a bet on the ingenuity and productivity of future generations. The pre-pandemic school system did far too little to instill confidence in this bet.

Shutting schools down and losing track of millions of students in the process makes matters worse still.

Our best hope for overcoming these challenges lies in an anti-fragile system of K-12 education that grows stronger in times of distress. Federal K-12 emergency funding, however, seems likely to simply preserve the past rather than bridge the way to a brighter future.

Bottom-up pressure, however, points entirely in the opposite direction. An entirely new sector of micro-schools has grown, home-schooling has surged, and state lawmakers have enacted the most far-reaching set of education choice bills in the nation’s history.