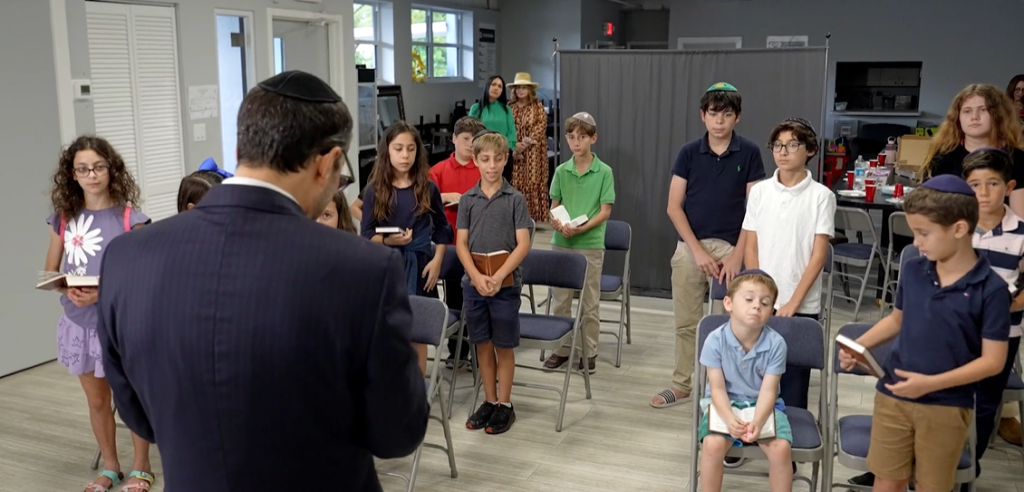

Rabbi Isaac Melnick likes to call it “the holy grail.”

Though the Orthodox Jewish leader and founder of Shorashim Academy doesn’t intend it as a religious reference, it serves an apt metaphor for what education entrepreneurs cite as their most difficult challenge: finding and securing a home to carry out their dream.

“A saying from one of our great sages of the last 100 years is that to start a yeshiva, or a Jewish school, you have to have a certified ‘Meshugener,’ a crazy person to take this on themselves,” Melnick said. “Because on paper this doesn’t make sense. If someone wants to be an entrepreneur, this is probably one of the riskiest, diciest ways to start a business. It’s just fraught with uncertainties.”

Melnick’s quest began last year after he was named a fellow in the Founders Program of the Drexel Fund, a national non-profit organization with a mission of equipping entrepreneurs to start or expand innovative learning programs by providing training and grants.

The fund also provides funding to support the new schools in areas that seek to help students in underserved areas. Florida and other states with robust education choice scholarship programs, provide fertile ground for qualifying founders and startups.

“I’d say that’s probably the biggest hangups,” said Eric Oglesbee, an alumnus of the Drexel Fund founders program who now serves as its director. He said the topic came up at a recent information session in which fellows said the biggest lesson learned over the past seven months had been the difficulty of finding and securing a location.

“It takes forever to find a spot that that can check all the boxes and get all the approvals,” Oglesbee said. “You have to figure out what’s not going to work but also know your model well enough to know what’s going to work.”

Oglesbee said while searching for a site for his River Montessori High School in South Bend, Indiana, three possible locations fell through before he and his team finally landed one. In addition to finding the site, founders must then contend with local government rules regarding zoning, construction and fire codes.

Because the rules are set locally, they often force founders to navigate a patchwork of regulations of varying stringency depending on the location of possible sites. A Utah lawmaker filed a bill this year to create uniform rules for innovative learning communities, often referred to as microschools. But the measure, which had been modeled after laws governing charter schools, failed in the Senate.

“Just because a site is in an area zoned for a school, it doesn’t mean you get approval,” Melnick said. “It just means you get to have a conversation.”

That conversation typically involves a list of responsibilities the entrepreneur must bear, such as a traffic study to make sure the roads can handle the car trips the new school will generate, as well as a list of renovations to bring buildings up to the latest codes.

Those responsibilities also come with a hefty cost that the founders and their team must bear.

Gretchen Stewart, a Drexel Founders fellow from Tampa, Florida, is working to open Smart Moves Academy, a motion-based school that caters to low-income students with learning differences. Since 2021, she has been dealing with myriad challenges posed by her unique model, as well as soaring rent costs and a lack of overall availability in the school’s catchment area.

“It just became clear right away that this was going to be problematic,” said Stewart, a former public school teacher who drew the inspiration for the school while writing the dissertation for her doctorate in special education and educational neuroscience at the University of South Florida.

Stewart said she first considered churches near the east Tampa community she planned to serve, but the spaces were being used by nonprofits providing feeding programs for those facing food insecurity.

“That kind of wiped out the spaces we could have considered,” she said.

She added that larger churches in the area already leased to private schools, and many older churches lacked the space needed for her program, which requires each classroom to be 900 to 1,000 square feet to accommodate physical activity-based learning.

The model also depends on access to enough green space for students to play and learn outside three times a day.

“A lot of schools are in strip malls where kids don’t go outside or are playing on a blacktop portion of a parking lot, which is not something our model can accommodate,” Stewart said.

The same goes for access to natural lighting, which Stewart says is critical to learning and good health.

For now, the program is operating as a summer camp at USF, but even that is not large enough to allow for necessary gym equipment.

If all that wasn’t enough of a barrier, Tampa rents are skyrocketing.

“We looked at one place near USF, and they wanted $35,000 a month, and that’s without utilities and taxes,” she said. “We’re trying to serve families from lower-income communities, families who have historically not had access to private education and allow them to take advantage of Florida’s robust school choice program.”

Stewart has applied for grants and is talking to philanthropists about the needs her school would meet. While she says everyone agrees that it’s a good idea, no one has been willing to donate enough to fully fund it.

Some organizations, like the Cristo Rey Network of Catholic high schools, have been fortunate to secure transformational gifts, like the $7 million donation the Orosz family made to buy a 75,000-square-foot vacant building to start a new school in Orlando.

“Space is our last hurdle,” Stewart said.

Like his fellow Drexel founder, Melnick also failed to land big gifts.

He made pitch after pitch to wealthy individuals in South Florida about buying a building and leasing it to Shorashim Academy, but no one was willing.

“I thought that would be a win-win,” he said, adding that even when an educator entrepreneur finds a lease deal, landlords usually want to collect rent months before the school is able to open and generate revenue to pay the expenses.

“You’ve really got to have the perfect storm, the perfect set of circumstances, in order to execute on that vision,” he said.

Melnick also approached synagogues, but many already hosted schools. One possibility fell through because the synagogue didn’t match the Shorashim Academy leaders’ Orthodox beliefs. The situation seemed so daunting that Melnick and school leaders hit the phones in hopes of finding leads.

“Regretfully, it made me a little bit cynical,” he said.

Their persistence, or what Melnick credits as divine intervention, recently brought good news.

Shorashim Academy will open this fall at the Soref Jewish Community Center in Plantation, Florida.

They have added a coveted new tab to the school’s website: Location.