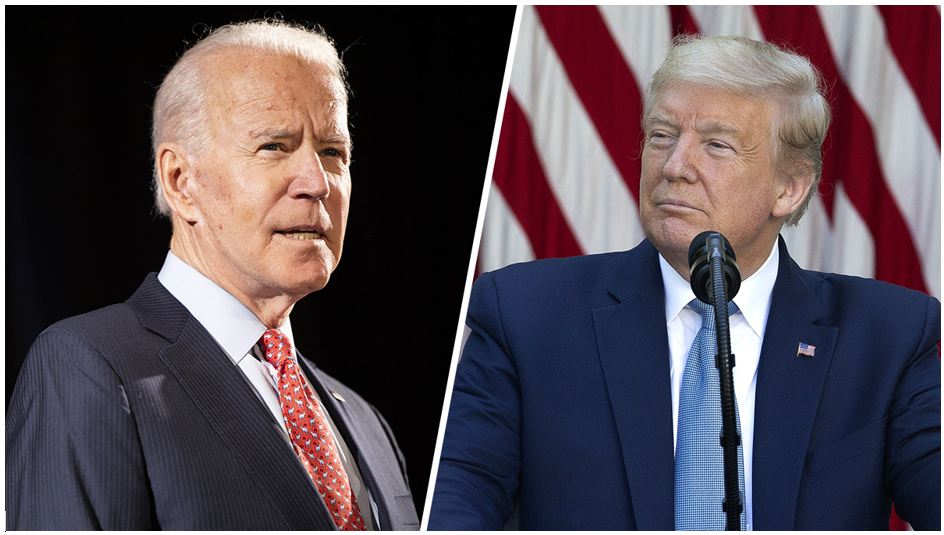

There is an election tomorrow, so go out and vote. But note that these elections were once far less apocalyptic in tone.

There is an election tomorrow, so go out and vote. But note that these elections were once far less apocalyptic in tone.

The 1920 presidential election, for instance, featured Warren Harding versus James M. Cox for all the presidential marbles, such as they were in those days. Cox survived a grueling contest against William Gibbs McAdoo and A. Mitchell Palmer to win the nomination of the Democratic Party on the 44th ballot.

If you haven’t heard of most of these people, don’t feel bad; you simply are engaging in rational ignorance. Harding defeated Cox and then died. He was succeeded by his vice president, Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge famously did and said very little as the nation’s economy boomed.

Presidential races were delightfully inconsequential back then compared to the modern end-of-days version where both major parties urgently assure us that tout est perdu if the other side wins. In reality, life goes on until the next Ragnarök election, and then the next. Some catastrophic policy mistakes made starting with Coolidge’s successor, however, are eerily reminiscent of the current K-12 calamity.

On the one hand, modern elections seem overblown. Matthew Ridley made the case in the Rational Optimist that one struggles to find a 10-year period of American life in which material conditions failed to improve despite our political follies. Take, for instance, the Great Depression, an era in which a bipartisan group of federally alleged Olympians made a whole series of catastrophic policy mistakes, including but not limited to the Republican Hoover Administration starting a global trade war.

The Federal Reserve tightened the money supply during the early years of the downturn. In addition, the non-stop administrative antics of the Democratic Roosevelt administration created enormous political and economic uncertainty. The country had experienced plenty of stock market crashes and downturns, but a decade-plus long depression? That took some truly misguided effort.

Sometimes the words “we’ve got to do something” can be the most dangerous phrase in the English language.

There was a lot of suffering due to these mistakes. Nevertheless, due to the normal improvement process of people grinding on problems and tinkering with products/services the average American was wealthier at the end of the 1930s than the beginning. Today, the average American lives far better than the richest person on the planet in 1920 in many aspects.

Education, however, has lacked a decentralized process whereby results continually improve, and thus stands out as a sore thumb against an overall trend of societal improvement. A tangled web of federal, state and local rules governs educators in an effort to standardize schools and outcomes. School district democracy is marked by low voter turnout, and thus high vulnerability to regulatory capture.

Spending was going up and scores down before the pandemic, and the pandemic has introduced a whole host of new problems.

Federal officials won’t be able to fix much of this regardless of who wins. The states face an enormous revenue shortfall, students have acquired learning gaps we are only beginning to measure, and an estimated 6% of students have received no instruction since the spring shutdowns. Women are leaving the workforce in unprecedented numbers which is going to hurt both family and government finances. White students currently have twice as much access to in-person instruction as students of color.

Never mind Baby Boomer teacher retirement; under typical state retirement rules, many Gen-X teachers are eligible to retire. Take, for instance, a teacher born in 1967 who began teaching in 1990. Under a “rule of 80” this now 53-year-old teacher with 30 years of experience became eligible for the typical state pension years ago. This wouldn’t be as much as a problem if college students were flocking into education training, but they have been shunning it.

This also would be less of a problem if the typical state retirement system had been properly capitalized, but it hasn’t.

A grand mess awaits whoever wins tomorrow, so good luck to them. The task of recovering from our education troubles and leading a broad reimagining of an antiquated K-12 system will primarily fall on our state and local leaders.

Keep them in your prayers, and God bless America.

Editor’s note: This column from redefinED guest blogger Chris Stewart first appeared Feb. 25 on Education Post.

Editor’s note: This column from redefinED guest blogger Chris Stewart first appeared Feb. 25 on Education Post.

I’m starting to notice a trend among the presidential candidates. I don’t think they’re vying to be a president who represents all Americans, just some. It sounds crazy but hear me out.

When Democratic frontrunners lavish attention on traditional public schools to the exclusion of charters, privates, and homeschoolers, it’s as if the worth of a child instantly plummets the moment they are enrolled in a disfavored school. As if their families don’t pay taxes and aren’t worthy as voters. Never mind the fact that many of the candidates have taken advantage of these same options.

Not to be outdone, President Trump got in on the action when he released a budget that cut funding for charter schools but increased funding for privates. Some of his supporters have told me not to worry because one, a president’s budget is a fictional thing, and two, the funding for charter schools is just being bundled together with other programs. It’s called “block granting” and that’s a good thing because it can give states the flexibility to use the money in a way that makes sense for their local context.

That sounds great in theory until you consider the fact that flexibility in a state like California, the largest charter system in America, could easily fall victim to union politics. Handing over charter school money would be a financial love letter to a fickle governor, one that would give him Thanos-like powers to snap his fingers and freeze charters startups.

But maybe I’m making too much of this.

The candidates would respond to me by saying they aren’t proposing the elimination of charter schools. They just want to slow their growth. And, the block-granting of federal funds isn’t the end-all of charter funding. And, after all, maybe there is more to life than charters. Most of the candidates are proposing enormous new investments that will grow school staff and provide more services to kids.

Who can complain about that? I can.

Yes, research shows that money matters in public education, but some of the nation’s biggest spenders are still hot zones of poor achievement and unacceptable results. Teachers unions and their allies have cleverly called for things like “community schools” as a main investment. It sounds good until you consider the fact that many of the existing community schools need help. Lots of it.

And no matter how much you wrap kids in services, it will still be a problem that our nation’s teachers aren’t recruited from the top of the class, their preparation is trash, and the support of many of those who teach in the toughest schools is nonexistent. To cover this with “I-stand-with-teachers” happy talk is to prove oneself incapable of true leadership.

We need a leader who will stand up for all families. We need someone who will fight for every American child equally. Today, parents from around the country are headed to South Carolina in hopes of meeting with presidential candidates to urge them to bring about “big, bold changes.” Because the fact is, every child deserves a better education, and our current system isn’t offering that.

We need people who can bring us together rather than continuing the bad practice of pitting parents against each other, then siding with the groups that want one form of schooling to be the only form of schooling.

Which leader is that?

I’m looking.