Florida’s Reading test results in the National Assessment for Education Progress (NAEP) weren’t all bad news, but things look much worse for Math scores.

Florida’s Reading test results in the National Assessment for Education Progress (NAEP) weren’t all bad news, but things look much worse for Math scores.

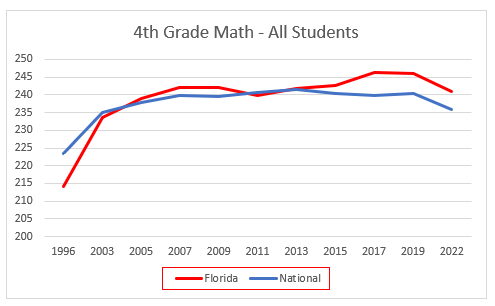

Where Florida’s fourth-grade Reading test scores dropped by an average of 0.6 points across all subgroups, students lost an average of 5.2 points in fourth-grade Math. The results were even worse for eighth graders.

Where Florida’s fourth-grade Reading test scores dropped by an average of 0.6 points across all subgroups, students lost an average of 5.2 points in fourth-grade Math. The results were even worse for eighth graders.

It’s worth noting that Florida’s declines in NAEP Math scores mirrored the declines seen in the national average, but that average is both richer and whiter. When adjusting for race and income, Florida tends to dominate the national rankings, while Florida’s Reading performance tops the charts.

Despite being a majority-minority state – Florida has a larger than average low-income student population – the state’s fourth-grade students beat the national average in Math. Florida’s learning loss was about the same as the national average, with students losing 5.1 points compared to a 4.6 decline nationally, the equivalent of losing about a half year of learning.

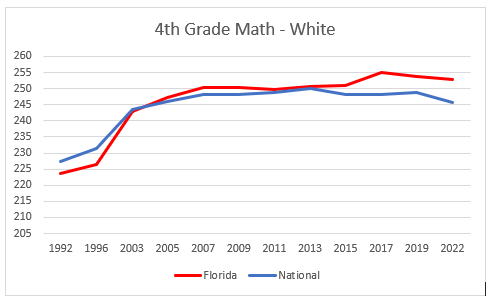

Florida’s white fourth-grade students lost 1.1 points compared to 3.1 points nationally.

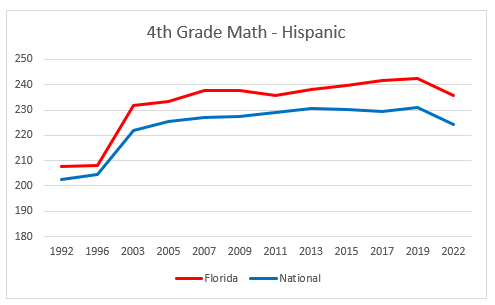

Unlike the more uniform learning losses for Reading, Florida’s minority students saw a larger learning loss in Math than white students. Fourth-grade Hispanic students in Florida and nationally lost about the same 6.4 points compared to 6.5 points.

Unlike the more uniform learning losses for Reading, Florida’s minority students saw a larger learning loss in Math than white students. Fourth-grade Hispanic students in Florida and nationally lost about the same 6.4 points compared to 6.5 points.

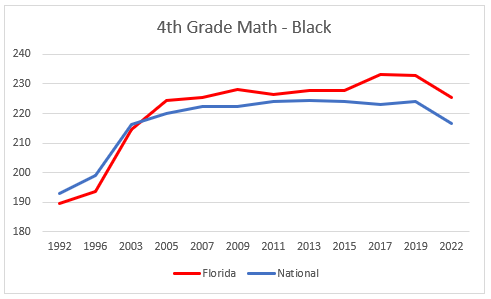

Black students in Florida lost 7.5 points compared to 7.4 points nationally. Both Black and Hispanic students lost about a half year of learning according to the fourth-grade math scores.

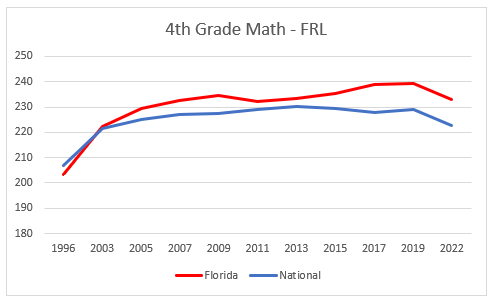

Low-income students, defined as students eligible for free or reduced-priced lunches, saw a 6-point learning loss compared to 6.2 nationally. Overall, Florida’s low-income students still score 10 points more -- about a grade level higher -- than their counterparts nationally.

Low-income students, defined as students eligible for free or reduced-priced lunches, saw a 6-point learning loss compared to 6.2 nationally. Overall, Florida’s low-income students still score 10 points more -- about a grade level higher -- than their counterparts nationally.

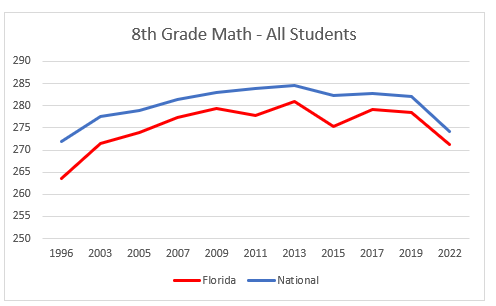

Research shows that without a strong foundation in early grades, older students have to play catch up. That is true with Florida. The state’s overall student population is now about 3 points behind the national average.

Research shows that without a strong foundation in early grades, older students have to play catch up. That is true with Florida. The state’s overall student population is now about 3 points behind the national average.

Students nationally saw a slightly larger decline at 7.7 points of learning loss compared to 7.3 points in Florida. A 7- to 8-point decline means students lost almost a year’s worth of learning between 2019 and 2022.

Students nationally saw a slightly larger decline at 7.7 points of learning loss compared to 7.3 points in Florida. A 7- to 8-point decline means students lost almost a year’s worth of learning between 2019 and 2022.

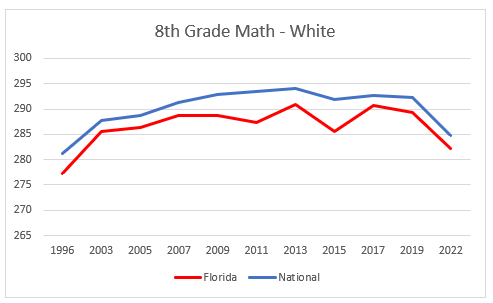

Florida’s white eighth-grade students perform below the national average in Math. Florida students saw a 7.3-point decline compared to 7.6-point decline compared to the national average.

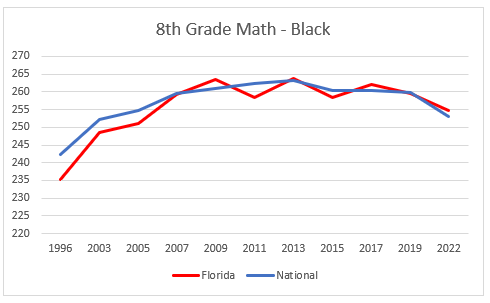

Florida’s black students performed slightly better than their peers nationally and lost 4.6 points compared to 6.8 points nationally.

Florida’s black students performed slightly better than their peers nationally and lost 4.6 points compared to 6.8 points nationally.

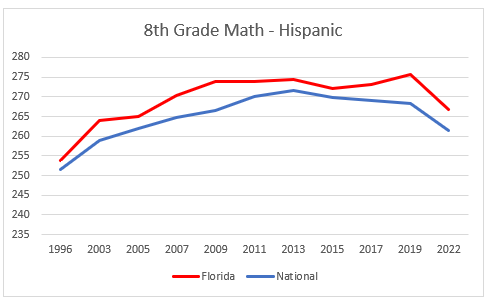

Hispanic students also performed better than their peers nationally, scoring about half a grade higher. However, Florida’s Hispanic eighth-grade student population lost 8.8 points compared to 6.8 points nationally.

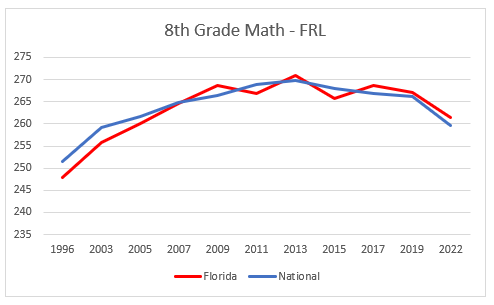

Eighth graders eligible for free or reduced-priced lunch barely edge out the national average in raw scores and in learning losses. Florida’s low-income eighth graders lost 5.6 points compared to 6.7 points nationally.

Eighth graders eligible for free or reduced-priced lunch barely edge out the national average in raw scores and in learning losses. Florida’s low-income eighth graders lost 5.6 points compared to 6.7 points nationally.

Florida students tended to have smaller learning losses than the national average. Low-income and minority students in Florida also tended to perform better than their peers nationally.

Florida students tended to have smaller learning losses than the national average. Low-income and minority students in Florida also tended to perform better than their peers nationally.

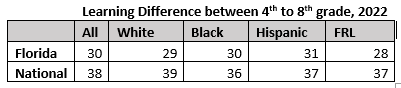

Looking at raw scores, Florida bests the national average in 8 out of the 10 subgroups examined above. Only eighth grade students overall and eighth grade white students lose out to the national average. The national average, however, shows stronger learning gains between fourth and eighth grades.

Subgroups nationally have nearly a difference of four grades in learning between fourth and eighth grade, while Florida tends to have about a three grade level difference.

Subgroups nationally have nearly a difference of four grades in learning between fourth and eighth grade, while Florida tends to have about a three grade level difference.

Overall, viewing Florida’s fourth and eighth grade math scores confirms that the state does a great job educating students in early grades, but the rest of the nation is able to catch up by the time students reach eighth grade.

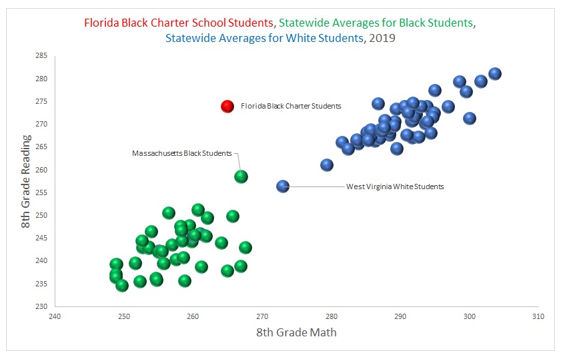

Back before the 2019 release of the “Nation’s Report Card,” I predicted that somewhere out there in the four tests – fourth grade and eighth-grade Math and Reading – a statewide score for Black students would exceed a statewide score for white students for the first time in the history of NAEP testing.

Back before the 2019 release of the “Nation’s Report Card,” I predicted that somewhere out there in the four tests – fourth grade and eighth-grade Math and Reading – a statewide score for Black students would exceed a statewide score for white students for the first time in the history of NAEP testing.

It happened! Black students in Massachusetts narrowly edged out white students in West Virginia this year on eighth grade Reading. Delightfully, Black students attending Florida charter schools clobbered both of them, by the way.

Yes, West Virginia has the lowest scoring white students, and yes, those students are far below average compared their peers, and yes, this is nowhere close to good enough for either Massachusetts Black student or West Virginia white students. Yes, the difference in scores may have been within the margin of sampling error.

Having said all that, this had never happened before in decades of NAEP exams. This was an important milestone in closing achievement gaps.

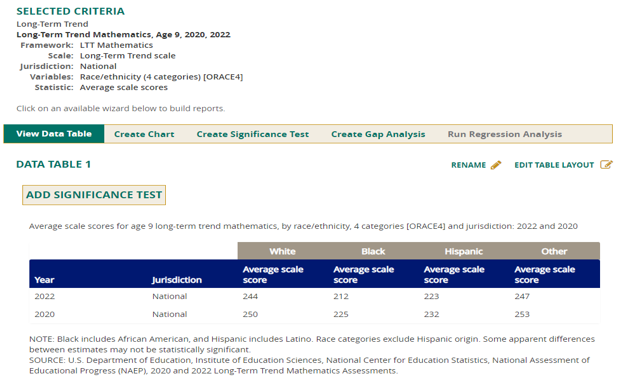

Last week, NAEP released Long-Term Trend data for 2022. One pandemic goat-rodeo response later, any hope of a statewide sample of Black students closing the gap with any state’s sample of white students is gone.

On these exams, 10 points roughly approximates an average year of average academic progress. The national white-Black gap expanded from 25 points in 2020 to 32 in 2022.

On these exams, 10 points roughly approximates an average year of average academic progress. The national white-Black gap expanded from 25 points in 2020 to 32 in 2022.

Black students lost about twice as much as white students between 2020 and 2022. Higher income families were doubtlessly better situated to compensate for the absence of in-person schooling. The students “left at home with a jar of peanut butter and a spoon and told not to answer the door” appear to be the only group bearing the consequences for decisions they had no voice in making.

Your author fears that no one reading this post will live long enough to see the 2019 milestone reached again. State level NAEP results will be released in a matter of weeks and the full extent of the fiasco will stand revealed.

Stay tuned to this channel.

Editor’s note: This commentary from R. Craig Wood, professor of educational administration at the University of Florida, appeared Tuesday in the Gainesville Sun.

Editor’s note: This commentary from R. Craig Wood, professor of educational administration at the University of Florida, appeared Tuesday in the Gainesville Sun.

Much of the popular discussion involving public elementary and secondary education revolves around terms such as “social justice” and “systemic racism,” although these terms are not consistently defined or understood by those utilizing them.

Specifically, it is the achievement gap between majority and minority students that is reflecting these specific concerns by those advocating “social justice.” Despite a range of attempts, the achievement gap has steadily persisted throughout the state and the nation.

In the state of Florida, the achievement gap has remained approximately the same over the years. Large achievement gaps also exist between majority students and those who are English language learners, and who come from homes of poverty.

Despite the continuing attempt of large public school districts in the state to close the achievement gap, the educational establishment refuses to address the most obvious of alternatives: choice. The left-wing educational establishment fails to acknowledge the utilization of vouchers, charters, micro schools and even greater choice as a viable and cost-effective alternative to closing the achievement gap.

The facts are rather clear and obvious. The refusal of the left-leaning educational establishment, the teachers’ unions and state policy makers to acknowledge such a hybrid system does, in fact, demonstrate “systemic racism.”

To continue reading, click here.

Several weeks ago, we looked at American racial achievement gaps in math and reading from an international perspective using data from the Program for International Student Assessment, an international test that every three years measures reading, mathematics and science literacy of 15-year-olds.

In 2012, the PISA exam included subgroup specifically for Florida. Let’s take a look:

So, a couple of notes. This PISA data is from 2012. The National Center for Education Statistics shows that Florida’s white, black and Hispanic students all saw very large academic gains since the 1990s. We have reason to fear, therefore, that if the PISA exam had been given in, say, 1998, the results would have looked very frightening indeed. As it is, the results didn’t look so great in 2012.

Florida’s black students land in the vicinity of students in Chile and Mexico. Chile and Mexico spend only a fraction of what is spent per pupil in the United States and must contend with much larger student poverty challenges. Florida’s Hispanics scored higher, but still performed similar to students in Greece and Turkey, lower-spending countries.

The Third International Mathematics and Science Study exam from 2015 allows us to take a similar look at Florida subgroup achievement in international context. PISA and TIMSS test a different grouping of countries (with quite a bit of overlap) and test somewhat different things. Nevertheless, TIMSS also included Florida subgroups.

Here are the results for mathematics for nations and Florida racial/ethnic subgroups on eighth-grade math.

As was the case in the PISA data, American black students achieved similarly to students in nations that spend only a fraction of what American schools spend per pupil, and with more severe poverty challenges. Florida’s Hispanic students score higher but also find themselves outscored by countries such as Malta, Slovenia and Kazakhstan, which don’t begin to match American levels of spending. Florida’s Asian and Anglo students didn’t conquer the globe but had scores that were comfortably European if not Asian.

Make what you will of this information, but in my opinion, we have miles yet to go.

BRADENTON, Fla. – Lena Clark has a recurring nightmare. The former Army medic and Iraqi War veteran is trapped on the battlefield – bombs exploding, smoke everywhere – and desperately looking for the date in her contract that tells her when she can leave. She can’t find it. Nobody can help. The war drags on.

Brothers Frankie and Allen Clark are thriving at Visible Men Academy, an all-male charter school. Pictured here, the Clark family. (From left to right: Lena, Kennice, Allen, Frank and Frankie.)

Clark said the nightmare persists because it’s about her sons, Frankie, 11, and Allen, 10, and the hurdles they face as black males. It’s about the education she feels they must have – and she and her husband must give them – to navigate a world that can be hostile to children of color.

“I’m always going to be in a war for my children because I am raising black men,” Lena Clark said. “And that’s something I need my school to help me with.”

Thankfully, she said, she and her husband found that school.

For the past three years, Frankie and Allen have attended Visible Men Academy, a K-5 charter school south of Tampa Bay that is 100 percent male, 99 percent low-income, 96 percent black and Hispanic – and on the rise academically. The school emphasizes personalized instruction and character development. It’s big on expression through art and parental engagement. That combo, Clark said, has been a tonic for her boys.

“When they get up in the morning, they iron their own clothes and say, ‘We’ve got to be men today,’ “ she said. “If I have to pull them out for a dentist appointment, they’re like, ‘Mommy, what are you doing?’ They don’t want to go. They want to be in school.”

It wasn’t always that way.

Clark said she and her husband, Frank, removed their boys from their district school because the boys’ enthusiasm had begun to wane. Frankie and Allen are straight-A students. Clark said she pressed teachers for tougher assignments, but it didn’t happen.

When Frankie and Allen got home, they binged YouTube with Bill Nye the Science Guy, and devoured websites for brain teasers. That was good, but the Clarks also saw another sign their sons weren’t getting the intellectual nourishment they needed at school.

“We were higher than our grade level, but our teacher didn’t have anything for us beyond that,” Frankie said. “It wasn’t really challenging.”

Too often, Allen said, it was also frustrating.

“If a student had to be redirected,” he said, meaning steered back on track after dis-engaging or causing a disruption, “it was like, ‘Here we go again.’ “ (more…)

Editor’s note: This is the second post in our school choice wish series. See the rest of the line-up here.

I wish those who are outraged and protesting that “black lives matter” over the two-tiered policing and criminal justice system would connect the dots and express similar outrage over our two-tiered, state-operated, feudal education system. Why do so few similar demonstrations occur, and never with a statewide or national scope, about the outcomes American education provides to families generally, but particularly for African-Americans, when the effects on lives are at least equally devastating?

At the surface, America has these two exemplary 21st Century societal systems that represent the very core of its founding beliefs – equality, justice, and fairness. Criminal law is not race- or class-based as written in statute. Everyone is equal before the law and no one is above it. Public education is free and, since the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education U.S. Supreme Court decision, universally open and equal for all. The double standards that in fact exist are neither explicit nor openly condoned. We have reams of data to document the injustices at the hearts of both systems.

From speeding tickets to drug arrests through convictions to imprisonment, African-Americans (as well as Latinos and poor people of all colors) are disproportionately represented, often grossly so. In the 2011 U.S. Department of Justice’s report, Contacts Between Police and the Public, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that while white, black, and Hispanic drivers were stopped at similar rates nationwide, black drivers were three times as likely to be searched during a stop as white drivers, and twice as likely as Hispanic drivers. During a more than 20-year period, white secondary students were slightly more likely to have abused an illegal substance within a month than a black student, yet black youths were arrested at twice the rate. Although black Americans make up only 12.7 percent of the U.S. population, they make up 48.2 percent of adults in federal, state, or local prisons and jails.

All Americans accused of a crime have an absolute right to an attorney, but the quality of that defense is inconsistent at best. More than 70 percent of American public defenders’ offices reported extreme or very challenging funding issues in 2012. On average, each public defender handled more than one new case for every day of the year at a rate of $414.55 per case. Given that the poverty rate for both African-Americans and Latinos is about 25 percent compared with 9 percent for whites, many more minorities are affected by this overburdened system.

If convicted, Supreme Court decisions that have made an “inadequate defense” argument nearly impossible to win on appeal only further weaken efforts that advocates make for increasing funding for public defenders. Courts have upheld convictions even when defense counsels have slept during trials, used cocaine and heroin throughout trials, and admitted they had not been prepared on the facts or law of the case.

These “dots” that have stirred outrage connect easily into an education system that falls far short of its promise for equality and justice. As the Alliance for School Choice recently noted, 75 percent of state prison inmates are high school dropouts. This failure feeds the criminal justice system.

We are making slow progress to increase parental choice, but most students remain assigned to schools via ZIP code. (more…)

What would Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. say today about our schools? What approaches would he support to close achievement gaps? What would he think of school choice?

Over the past year, we asked a number of folks to weigh in on those questions. For a podcast last January, we asked the Rev. H.K. Matthews, a civil rights icon in west Florida who knew Dr. King. We asked others for a blog series that ran last August, on the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech.

As we celebrate MLK Day today, we thought it appropriate to highlight those posts. We know there are no easy answers, but we hope these voices contribute thoughtfully to the debate.

From H.K. Matthews: School choice: an extension of the civil rights movement

From Darrell Allison, president of Parents for Educational Freedom in North Carolina: Access denied, from lunch counters to zip codes

From John E. Coons, longtime school choice advocate: MLK and God's schools

From Vernard T. Gant, director of urban school services with the Association of Christian Schools International: The unrealized dream of educational justice

From Peter H. Hanley, executive director, American Center for School Choice: Parental choice would honor The Dream

Wendy Howard: Higher standards will mean our next generation is better prepared for college or the workforce. That’s good for kids, parents, taxpayers and our country.

Editor’s note: Wendy Howard is executive director of Florida Alliance for Choices in Education, a group that includes a wide range of school choice organizations, including Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog. A shorter version of this post ran this week as a letter to the editor in the Tampa Bay Times. Given Wendy’s conservative political bent, her staunch support for school choice and the concerns about Common Core, we thought it worthwhile to share a fuller version.

With attacks on the Common Core State Standards for education coming from both sides of the aisle, what are parents to think?

I’ve heard Common Core is Obama’s agenda to indoctrinate our children. I’ve heard it’s an unconstitutional federal takeover. I’ve even heard it’s a scheme to perform experiments nationwide on our next generation. After doing some research, I learned none of those concerns hold water. The bickering continues, however, while our children suffer the consequences.

The fact is, our kids need higher standards for education. Let’s look at a couple of disconcerting facts from the perspective of a parent with two children attending a public charter school.

Forty percent of Florida’s class of 2013 who took the ACT college entrance exam were graded “not college ready” in any subject, which is higher than the national average of 31 percent. As a parent, this has huge financial implications. If my children are part of these statistics, I will have to pay for remedial classes in college, something I simply cannot afford. As a taxpayer, I expect my child’s diploma to mean she actually succeeded in high school and can move right into college courses. As a nation, millions of kids and their parents are impacted each year when that turns out not to be the case.

Higher standards will mean our next generation is better prepared for college or the workforce. That’s good for kids, parents, taxpayers and our country.

Here’s another troubling statistic: Thirty percent of high school graduates can’t pass the U.S. military entrance exam, which is only focused on basic reading and math skills. At what point does the lack of high standards become a national security issue? If the learning gap between the U.S. and other countries continues to rise, which country becomes the next super power? What does our country look like in 20, 40, 60 years? I guess that depends on whether we look at the achievement gap between the U.S. and other countries as a crisis – or another issue we kick down the road. (more…)

Fifty years ago next week, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech to 250,000 people in Washington D.C. It remains one of the greatest speeches in American history, offering a sweeping vision of hope and equal opportunity in the midst of so much fear and turbulence.

Many of us will reflect on how far we have come, and how far we have to go, since Dr. King energized millions with his words - and there’s no doubt education will be part of those discussions. To that end, we’re running a series of posts next week on the Dream and our schools.

Many of us will reflect on how far we have come, and how far we have to go, since Dr. King energized millions with his words - and there’s no doubt education will be part of those discussions. To that end, we’re running a series of posts next week on the Dream and our schools.

We asked our bloggers to consider a scenario described by education leader Howard Fuller: On Feb. 1, 1960, four black students sit down at a lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. and are denied service. They spark the lunch counter movement, helping to focus the nation’s conscience on racial segregation. Now, four black students sit down at a lunch counter and they’re welcomed like other diners. But they can’t read the menu.

What do racial achievement gaps say about the state of Dr. King’s dream? How does our current education system expand or contract his vision of social justice and equal opportunity? Is there reason to be hopeful when it comes to school choice, educational quality and the academic success of low-income and minority children? Please join us, beginning Monday, to read what some of our bloggers have to say. And please add your thoughts to the discussion.

For many school choice supporters, enrollment growth across many sectors is reason to cheer. But new research may give policymakers pause about whether they're pursuing the options that result in the best academic outcomes.

William Jeynes, a professor at California State University, Long Beach, and a senior fellow at the Witherspoon Institute, found students in religious schools were, on average, a full year ahead of their peers in traditional public and charter schools. After controlling for parental involvement, income, race and gender, the students were, on average, seven months ahead.

The findings, recently published in the Peabody Journal of Education, were based on a first-of-its-kind meta-analysis of 90 studies that compared academic performance across the three sectors. Jeynes also found:

The implications for school choice, he said, are obvious. (more…)