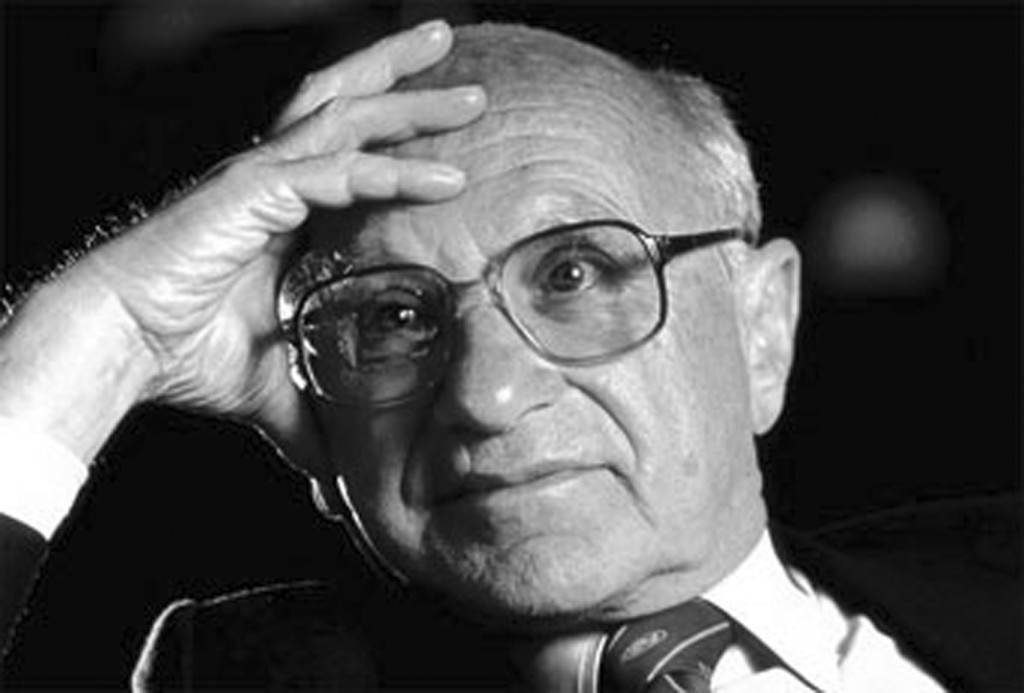

American economist Milton Friedman received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. His vision was to give parents, not government, control of their child's education.

In the 1960s, Milton Friedman was my repeated guest on “Problems of the City” on Chicago radio KQED-KFMF, and later, I was a guest on his TV show to debate United Federation of Teachers president Albert Shanker. We – Friedman and I, not Shanker – shared the hope for a free market in schooling but differed regarding both its justification and appropriate design.

He favored a subsidy of equal value for the child of every parent, then would let the market rip! It was to him an economic sin to favor lower-income families in either the amount of the subsidy or the design of regulation for participating schools. The focus for him was not on the role of the parent, but rather the achievement of simplicity and laisse-faire in the economy.

Friedman was never to change his mind; in fact, he took the opportunity along the way to promote just such an unregulated voucher as a popular initiative in California in 1978, designed so as to compete with a prior and more lower-income-oriented initiative written and promoted by Steve Sugarman and myself. So divided, neither proposal made it to the ballot.

He did, however, succeed at inspiring a covey of monied and dedicated marketeers who have to this day remained willing to support a let-her-rip approach to choice. Their generous enthusiasm has given birth to a covey of pure-market non-profit organizations, today’s most plangent cheerleaders for choice – that is, for equal subsidy for both the poor and for the already comfortable family, and with nearly zero regulation of the chosen providers. These well-intending market folk have succeeded largely in giving subsidized parental choice the image of Friedman himself.

This picture may have held very little glamour for voters, but paradoxically has been much appreciated by the captains of the public school unions; it allows them to picture subsidized choice as another deceit of the rich and powerful (other than themselves).

When Sugarman and I began designing model choice statutes in the ’60s, our first invention was a complicated device intended to arm the lower-income parent with an array of choices, including the level of the subsidy in both public and private sectors. Over time, our published inventions have become more simplified but ever with the central aim of empowering the lower-income parent to act as responsibly as does the comfortable suburbanite.

After this half-century of division between Miltonites and “voucher left” (their pet name for people like us), could it be that the time has come to consider what sort of compromise might give political life to our shared democratic hope? Could we learn a bit from Ohio, Florida and Washington, D.C.? Could it be both “fair and free market” for us lefties to concede at least a trophy amount to the well-off in recognition of their civic role as parent, while awarding the poor the full economic reality of that same parental responsibility and authority?

The success of any choice system in empowering the poor would, of course, require some commitments from the (freely) participating school – private or (at last) “public.” For example, the participating school could retain complete liberty to select two-thirds of its admissions, but then to select the rest at random from among its unchosen applicants.

In designing such statutory proposals, a half-dozen other forms of commitment by the participating schools would be considered to ensure fairness. Each of these compromises in design could be bargained by the “voucher left” and the Miltonites. These variations were examined in some detail and modeled in our 1978 book, “Education by Choice: The Case for Family Control” – and in our later published models.

It will not necessarily be politically hurtful to the cause of choice that Betsy DeVos will be gone, and that the president-elect appear as mendicant of the union elites. The individual state will still decide whether and in what precise form those who need choice should receive it. And, at some point, in another paradox, SCOTUS may well take occasion to lend its voice to the rescue of the penniless under the Constitution. This could well be the time for voucher folk, “left” and right, and in every state, to become happy co-conspirators.

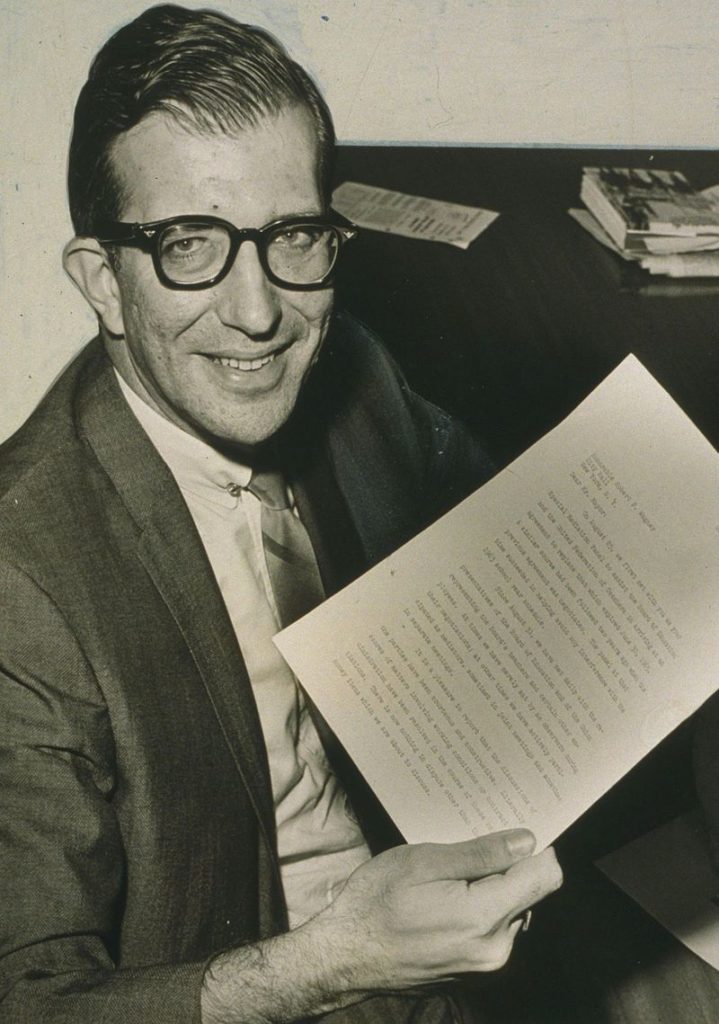

Given Al Shanker’s role in crushing the efforts of minority communities in New York City to have more control over their local schools, his 1989 call for more decentralized decision making in public education seems disingenuous. He never made any significant efforts to put his rhetoric into practice within public education.

Scott Kent’s recent redefinED post on Al Shanker’s New York Times column comparing our public education system to Soviet-style communism has raised eyebrows -- and many questions.

In 1989, Shanker (who died in 1997) was president of the American Federation of Teachers and arguably our nation’s most famous teachers union leader when he wrote:

“Business as usual in the public education system is going to put us out of business…It’s time to admit that public education operates like a planned economy, a bureaucratic system in which everybody’s role is spelled out in advance and there are few incentives for innovation and productivity. It’s no surprise that our school system doesn’t improve: It more resembles the communist economy than our own market economy…no law of nature says public schools have to be run like state-owned factories or bureaucracies.”

While Shanker’s words may seem bizarre, especially given the conservatism of today teacher union leaders, in the context of the 1980s and early ‘90s they weren’t that strange. The 1980s were the era of teacher empowerment and site-based decision making, at least rhetorically. The National Education Association (NEA), the nation’s largest teachers union, took the lead with several projects that explored giving teachers and principals more control over how their schools and classrooms operated. (more…)

Today's split over school choice within the Democratic Party isn't new. Fifty years ago, the teachers unions faced off against black and Hispanic families in NYC who had a different vision of public education. The union led by Al Shanker won. Charles Frattini/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

The crowd shots that illustrate the Democratic Party’s big split over school choice are, in one key respect, starkly black and white. Or, at least, black, brown and white.

On one side: Thousands of teachers on strike, from West Virginia to Oklahoma to Arizona. Overwhelmingly white.

On the other: Thousands of parents at school choice rallies, from Florida to New York to Illinois. Overwhelmingly black and Hispanic.

On the other: Thousands of parents at school choice rallies, from Florida to New York to Illinois. Overwhelmingly black and Hispanic.

None of these recent events happened at the same time. And to be clear, last spring’s strikes were primarily for better pay, not against school choice. (Though unions and their allies haven’t been shy in trying to scapegoat choice for skimpy raises, hot air, gang violence … ) But 50 years ago, these Democratic camps were face to face, over picket lines in The Big Apple, over competing visions of public education. That epic power struggle helped set the stage for today’s divide over school choice.

The battle over “community control” rocked the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn in 1968. It pitted the predominantly white teachers union in New York City, led by Al Shanker, against black and Puerto Rican parents.

Tired of white resistance to court-ordered integration, communities of color in NYC decided to pursue an alternative. They pushed for changes in local governance, resulting in a pilot that created a community-based school board.

Community control wasn’t school choice, but the movements share roots.

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian James Forman Jr. notes a few in “The Secret History of School Choice: How Progressives Got There First.” Community control advocates were tired of ceding to bureaucrats. They believed empowered community groups, closer to students and parents, could better create successful schools. Forman even likened the community school board in Ocean Hill-Brownsville to another revolutionary institution of that era, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

It didn’t take long for the pot to boil over. In May 1968, the administration at one community school, P.S. 271, fired 13 teachers and six administrators it deemed ineffective. All but one were white.

The union response was shock and awe. Shanker called three strikes that paralyzed the city. More than 50,000 teachers went on strike. More than 1.1 million students were stranded.

White parents were outraged. But they blamed minority communities, not striking teachers. (more…)