by Allison Hertog

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings - they have the same parents but are often rivals - vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

Charter schools often have an awkward, if not contentious, relationship with their local districts. That makes sense, as the public charter school movement is essentially a reaction to what can be a cookie cutter way of educating kids in neighborhood schools. Yet charter schools are part of the very same district (or state) that funds the neighborhood schools. It’s as if they’re siblings - they have the same parents but are often rivals - vying for funding, control, students, and political power among other things. Some district/charter relationships are cooperative, but others are rancorous, as illustrated by recent disputes in New York City and Pennsylvania. Not surprisingly, both those disputes involved special education to some extent – probably the most complex, expensive and controversial area of teaching.

In most states, charter schools have the option of freeing themselves from these and other disputes by essentially becoming their own districts (legally termed Local Education Agencies or “LEAs”). But the vast majority of charters, even in states like California, where they have the option of becoming their own LEAs, have not taken on the responsibility of fully controlling their own special education programs – possibly out of fear, ignorance or politics. Fortunately, many of the more competent and high-achieving California charters - like KIPP, Aspire, and Rocketship - have chosen the path of autonomy and accountability and are leaving behind special education disputes with districts.

Where I work in Florida, where essentially charter schools don’t have the option of becoming their own LEAs (as is also the case in places like Virginia, Maryland and Kansas, and in New York for special education purposes), these special education disputes are problematic for many reasons. They’re terribly inefficient; they come at the expense of children; and they fly in the face of the charter school movement’s supposed commitment to autonomy and accountability.

To illustrate why it makes sense that some of the most competent charters are choosing to become their own LEAs and take full responsibility for special education, I’m going to use a business analogy that doesn’t carry the emotional baggage of disabled children.

Imagine a young entrepreneur who runs a new and successful Italian restaurant called “Vagare.” Vagare (i.e., the charter school in this story) has grown to serve roughly 300 customers a day. But in this city there’s a local corporate giant: “The Italian Restaurant Company” (i.e., the district). Founded in the late 1800’s, the IRC has virtually cornered the market on Italian restaurants. It serves thousands of customers daily, owns hundreds of locations, and controls restaurant supply firms and food supply chains. You get the picture.

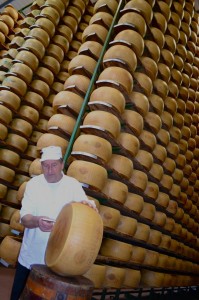

The IRC has contracted out some of its locations and provides certain supplies to Vagare and other smaller restaurants. Vagare locally sources most of its ingredients except for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, which, by contract, it is required to obtain from the IRC, which buys it in bulk from Italy. (more…)