A three-day exhibit hosted by Black Minds Matter details the history of African American people's pursuit of education freedom from the Antebellum Period though today with many options for education choice.

Black Minds Matter recently hosted a pop-up exhibit to showcase the history of African Americans’ pursuit of education freedom, including showcasing Black school founders who are creating learning institutions with help from Florida education choice scholarships.

The three day pop up exhibit, titled Self-Determined: The Secret History of Education Freedom, hosted by Black Minds Matter at the Ritz Art and Theatre Museum, included founders of Black schools from the Black Minds Matter. director of Black-owned schools.

The exhibit was meant to showcase Black education beginning in the Antebellum Period and continued through Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Era, to present day, with education choice options ranging from district, charter, homeschools, magnet, virtual and private schools.

Some Black school founders spotlighted during the exhibit included Cameron Frazier, Dwayne Raiford Bishop, and Lady McLaughlin. Their website has a directory of almost 400 black school founders.

Black Minds Matter was founded in 2020 by Denisha Allen, who benefited from the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program. Allen went on to work for the U.S. Department of Education under Secretary Betsy DeVos and now serves as a senior fellow at the American Federation for Children.

For more information about the exhibit or the directory, visit Black Minds Matter.

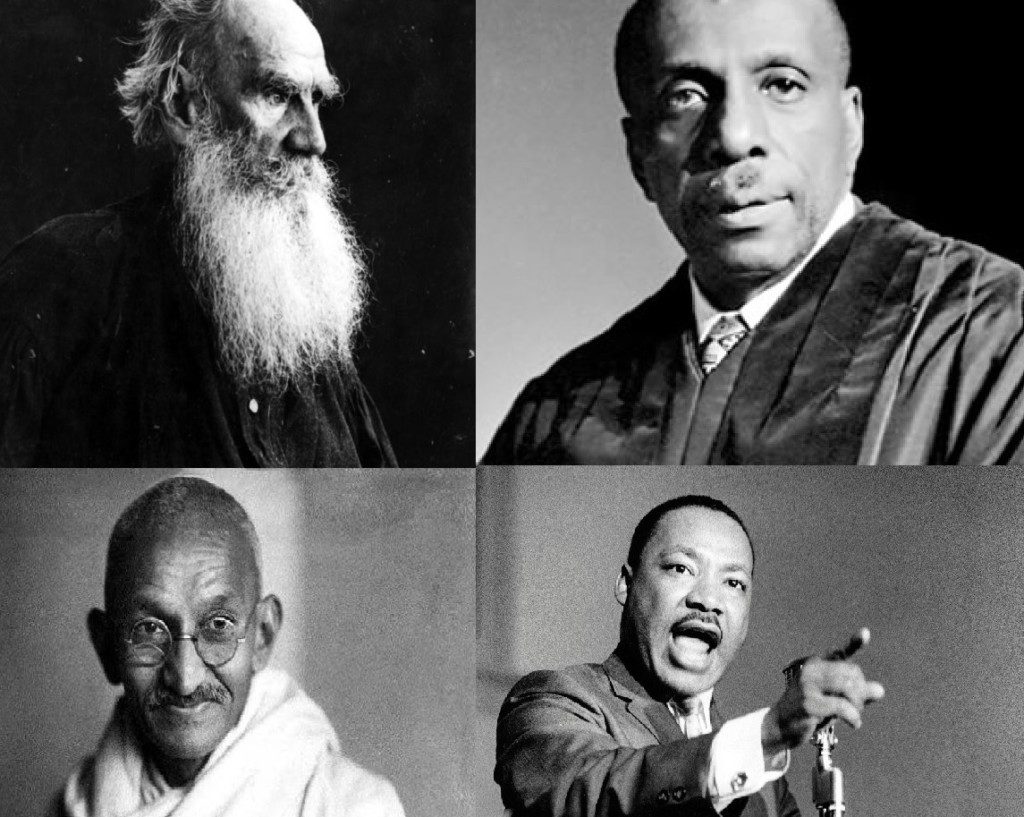

Four social justice advocates whose philosophy may be applicable to today’s education freedom movement

“That this social order with its pauperism, famines, prisons, gallows, armies, and wars is necessary to society; that still greater disaster would ensue if this organization were destroyed; all this is said only by those who profit by this organization, while those who suffer from it – and they are ten times as numerous – think and say quite the contrary.” – Leo Tolstoy, The Kingdom of God is Within You

The early years of the 20th century saw two incredibly significant events in the struggle for African Americans to achieve equal rights. Eventually, the positive development overcame the negative, but only with great sacrifice on two continents and decades of determined effort and inspired leadership. As we celebrate Black History Month, some time to reflect upon this magnificent record is in order.

Let’s get the negative event out of the way first. In 1910, a group of Progressive Republicans teamed with Democrats to strip Speaker of the House Joseph Cannon of the power to appoint committee chairmen. Chairmen came to be appointed by seniority, which not only decentralized power in the House, but enormously empowered Democrats from the old Confederacy. The Republican Party – the party of Lincoln – wasn’t competitive in the South once southern racists saw to it that former slaves couldn’t vote through Jim Crow laws. Intended or not, this “Cannon Revolt” enormously enhanced the power of segregationists for decades.

The Old Bulls, as the committee chairmen came to be known, ruled their fiefdoms with an iron fist. They decided which bills would get hearings and which would die. They said “Jump,” and the rest of the committee said, “How high?” Disproportionately, the Old Bulls were defenders of segregation.

Any change in American tax policy, for instance, had to begin in the House Ways and Means Committee. If you wanted to change something about taxes, and many people did, Rep. Kyle K. Klan, serving in his fifth term as chairman, decided which tax bills received hearings and which did not. If you already guessed that the Right Hon. Kevin K. Klux was biding his time waiting to replace Kyle when he finally went to pick cotton in Hell’s sharecropping plantation, give yourself a gold star, because that is essentially how things worked.

The Old Bulls ran the House for a mere 60 years and change, but in the end, a letter sent from a Russian to an Indian in 1908 ended their reign of error. This, in fact, is where the story gets really interesting.

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy was born into an aristocratic Russian family in 1828. An enormously successful author, Tolstoy experienced a moral crisis and a spiritual awakening in the 1870s. Tolstoy’s reading of the Sermon on the Mount left him with a unique Christian pacifist/anarchist perspective, reflected most notably in The Kingdom of God is Within You. In this book, Tolstoy made the case that the Sermon on the Mount commanded an end to all violence, even defensive violence. Tolstoy, noting the nonviolent teachings of the New Testament and the nonviolent resistance of the early Christian Church, called for non-violent resistance to oppression.

In 1908, Tolstoy wrote a letter to a young Indian lawyer living in South Africa laying out a path of non-violent resistance. In 1914, this lawyer, Mahatma Gandhi, returned to India and commenced a decades-long non-violent resistance for Indian independence from British rule.

During the struggle for Indian independence in 1936, the Christian Student Society of India sponsored a delegation of Black American ministers to tour South Asia. Howard Thurman gave dozens of lectures in India as part of this tour and met with Gandhi. During this meeting, Gandhi asked the Black ministers why they had adopted the religion of their oppressors. This was a statement filled with unintentional irony. As a lifelong Anglican, I’ve observed that Gandhi, although a Hindu, was closer to practicing the religion of his oppressors than his European colonial overlords.

Thurman then served as a key mentor to Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders of the American Civil Rights Movement. As with Tolstoy and Gandhi, Thurman served as the vital theoretician in aid of the implementer of the strategy of non-violent resistance. Thurman assisted King in developing the non-violent resistance movement, which ultimately led to the successful passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. For all their power, fear and hatred, the Old Bulls stood defeated by a still greater power.

Sometimes it is said that the parental rights movement is the Civil Rights struggle of the 21st century. It is true that our case for equality of opportunity is rooted in justice and fairness. It is equally true that the status quo provides the least to the children starting with the least, and the most to the children starting with the most. I also believe that any attempt to address poverty without addressing a system that spends like Luxembourg but produces results for African American and Hispanic children closer to Mexico is doomed to bitter disappointment.

Black History Month is an appropriate time for the education freedom movement to consider how Tolstoy, Gandhi, Thurman and King would advise us today. What can we learn and apply from these and other leaders of the past? It took not only decades of tireless effort for Gandhi and King and their followers to defeat their oppressors, but also a willingness to feel compassion for their oppressors.

Can we muster that level of perseverance and wisdom? It may, in fact, be required.

Editor’s note: This February marks the 43rd anniversary of Black History Month. redefinED is taking the opportunity to revisit some pieces from our archives appropriate for this annual celebration. The article below originally appeared in redefinED in March 2017. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis visited the school featured in this article while on the campaign trail.

Angela Kennedy’s decision to quit being a public school teacher was driven by a steady drip, drip, drip of frustration.

Dr. Angela Kennedy was a 14-year veteran of public schools when she left to start her own private school. She had been a classroom teacher and instructional coach, and had also coordinated curriculum compliance for English language learners. “I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option,” she said.

In her view, teaching had become too scheduled and scripted, with new teacher evaluations rewarding conformity more than effectiveness. Cohort after cohort of low-income kids continued to stumble and fall, while people far from classrooms continued to impose mandate after mandate. Her passion for teaching began to fade.

Kennedy considered becoming an administrator, so she could attempt reform from within. But ultimately, she took a leap of faith. After 14 years in Orange County Public Schools, she did what educators in Florida increasingly have real power to do: She started her own school.

Deeper Root Academy began three years ago, with three students in Kennedy’s home. Now it’s a thriving PreK-8 with 80 students and nine teachers, including seven who, like Kennedy, once worked in public schools. Most of the students are black, and 80 percent are from in or near Pine Hills, a tough part of Orlando that drew President Trump to another private school this month.

“It was that back and forth, thinking about where I could be the most impactful,” Kennedy said. "Would it be to stay and try to start a change? To try to deal with a mammoth system? Not likely that I’m going to get very far ... "

"But what I could do is give people an option. And that’s where this school came from. I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option.”

"But what I could do is give people an option. And that’s where this school came from. I wanted parents and students and teachers to have another option.”

Kennedy had options because parents had options.

Florida offers one of the most robust blends of educational choice in America, which is why Education Secretary Betsy DeVos gives it a nod. Forty-five percent of Florida students in PreK-12 attend something other than their zoned district schools, with a half-million in privately-operated options thanks to some measure of state support.

Charter schools, vouchers, tax credit scholarships and education savings accounts are all opening doors for Florida students. With far less fanfare, they’re doing the same for teachers.

“In my school,” Kennedy said, “I have the liberty to do what’s best for my kids.”

At Deeper Root, she and her staff are guided by the theory of multiple intelligences. Parents like it. Enrollment is rising fast from word-of-mouth referrals.

About 50 students attend with help from choice programs – tax credit scholarships for low-income students, McKay vouchers for students with disabilities, and Gardiner Scholarships, an education savings account program for students with special needs such as autism. The tax credit and Gardiner programs are administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

It’s unclear how many of Florida’s 50,000-plus private and charter school educators once taught in district schools. But it’s easy to find examples of teachers who migrated from one sector to another (see here, here and here). And it wouldn’t be surprising, given the growth in choice programs, that the number of crossover teachers is rising too.

Kennedy said colleagues in district schools frequently call, wanting to know what it’s like to teach in a school that she herself shaped. Many are as frustrated as she was, and intrigued by the new possibilities. It’s highly unlikely, she said, that a massive system compelled to be “uniform” can ever meet the needs of every teacher. Just as with students, some teachers won’t fit the mold.

“I don’t think that anyone had malicious intent,” Kennedy said of the regulations that guide the state system. “I think they’re trying to get a structure in place that’s uniform.”

But “teachers are not robots.”

Deeper Root moved from Kennedy’s home, to a storefront in a shopping plaza, to now, the leafy campus of a trim, modern, Presbyterian church. At a Black History Month event, students in crisp uniform shared their knowledge with peers and parents in the church auditorium. One expounded on the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution. Several gave a presentation about the slave ship Henrietta Marie. A fourth grader, poise far beyond his years, recited portions of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”:

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, "Wait."

Kennedy considered a charter school, but decided the regulations were still too much. More importantly, she wouldn’t be able to create the faith-based environment she and her parents want.

Deeper Root students take Bible class and go to chapel every Wednesday. But their curriculum is not faith-based. The school teaches Florida state standards, which are based on Common Core. Many of Kennedy’s students arrive after stints in Florida public schools, and most will return there for high school. “I want them prepared,” she said.

Preparation includes life lessons too. Students grow cabbage and broccoli in planter boxes made from old shelving. They take field trips to Publix to learn how to read labels and choose healthy foods. They visit restaurants so they can order from the menu and leave a tip.

While choice can empower teachers, it’s still not easy, Kennedy said. Going solo was scary, particularly because she had no experience with the financial side of school operations. At one point, a bad business relationship drained her investment and forced her to take out loans.

The learning curve was painful, but compelled her to quickly learn the essentials. Now, Kennedy said, she can advise other educators who want to make the leap – and serve as proof it can be done.

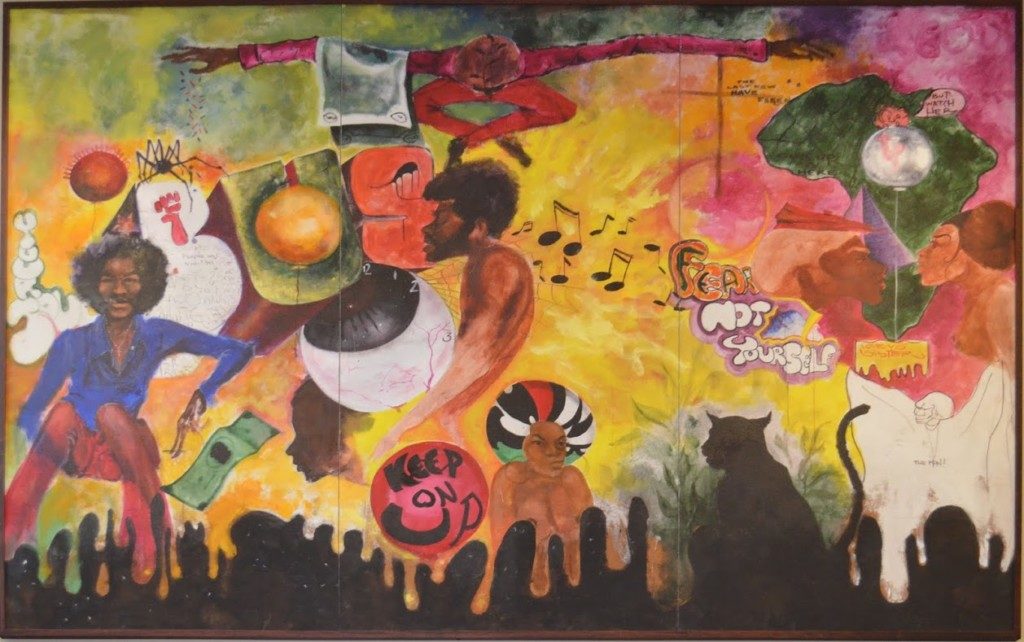

One of a series of murals covering the walls of the Center for Pan-African Culture at Kent State University, dedicated to a group of Kent State students called Black United Students, who first proposed the adoption of Black History Month

Editor’s note: This February marks the 43rd anniversary of Black History Month. President Gerald R. Ford, in the nation’s bicentennial year, urged Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” redefinED is taking this opportunity to revisit some pieces from our archives appropriate for this annual celebration. The article below originally appeared in redefinED in September 2016. Orange Park Normal and Industrial School was memorialized with a historical marker last year during Black History Month.

"We do not refuse anyone on account of race," Orange Park Normal and Industrial School principal Amos W. Farnham wrote to William N. Sheats in the spring of 1894.

In a letter to Sheats, Florida's top education official, Farnham described a faith-based institution in Clay County that was racially integrated 60 years before Brown v. Board of Education. Black and white students went to chapel, ate meals and learned together. Boys at the school, he wrote, "play baseball, 'shinney,' marbles and other games together."

Those words would soon spell trouble for the school, its students and its teachers.

Sheats, who would later be hailed as the "father of Florida's public school system," was an unrepentant segregationist and racist who launched an 18-year campaign to destroy the upstart school. His staunch opposition to racial integration fueled a decades-long crackdown on dozens of schools — many of them private institutions run by religious aid societies. It also inspired laws that subjected Florida to national ridicule and dashed hopes of racial progress after Reconstruction.

Known as the Sheats Law, a Florida statute barring black and white children from being taught in the same school was struck down in court, 120 years ago next month.

A school with a mission

Orange Park Normal and Industrial School was founded by the American Missionary Association (AMA), a protestant abolitionist society, with a mission to educate the children of freed black slaves.

The school took its name from the surrounding town, an enclave of northern transplants just south of Jacksonville on the banks of the St. Johns River. It first opened its doors to 26 students, including 16 boarders, in October 1891. By the fall of 1892, its enrollment swelled to 116 students.

The school provided a primary education for grades 1-8 as well as teacher training, vocational training and college preparatory coursework for older students in grades 9-12. In addition to typical courses of the day such as grammar, rhetoric, mathematics and calisthenics, the school also taught music, stenography, typing, agriculture, botany, horticulture, wood-working and printing. (more…)