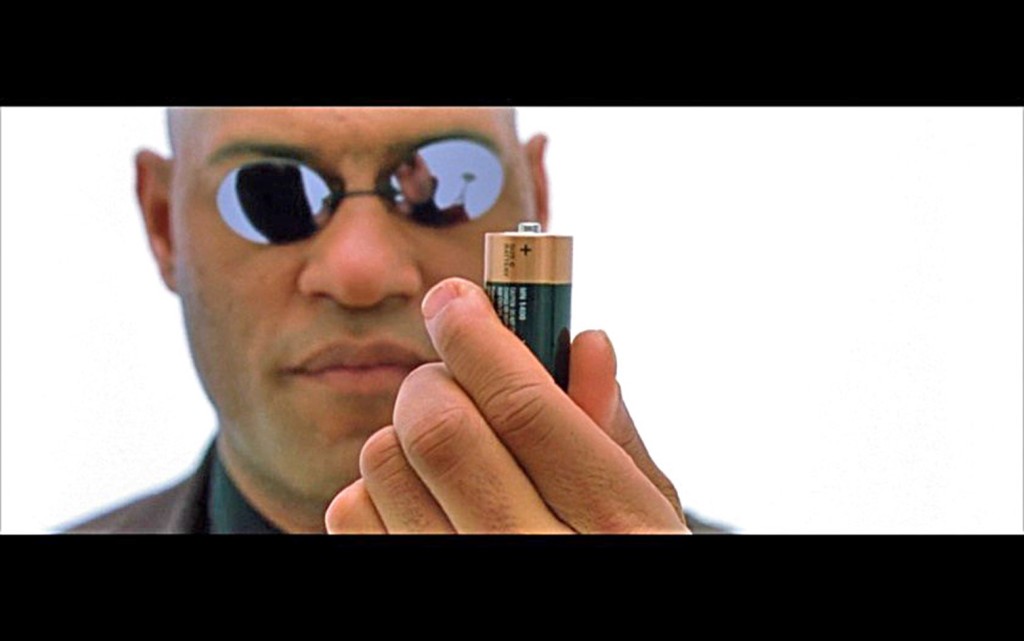

Go down, Moses

Way down in Egypt's land

Tell old Pharaoh

Let my people go

The Texas House of Representatives closed out the 3rd special session by filing a deeply flawed ESA bill but never held a hearing on it. Stay tuned for further developments. Meanwhile, the Texas Tribune filed a fantastic piece featuring three Dallas Black mothers who support a choice program in order to allow themselves and others in their communities to run and sustain their own schools. This is an amazing piece of journalism that looks past spokespeople with dueling sets of talking points in Austin to talk to real people and explore their concerns. You should read it and share it widely.

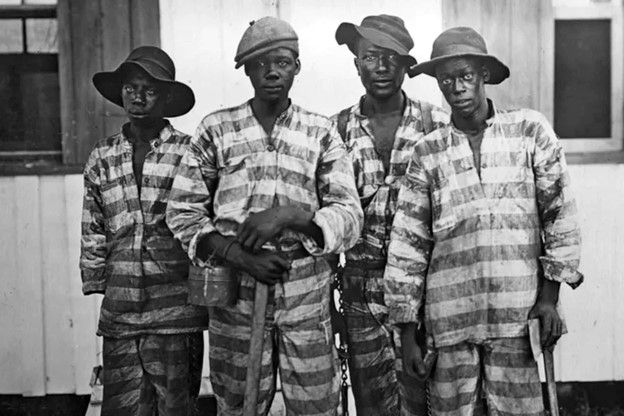

An earlier post on this blog described the era of peonage, whereby private interests availed themselves of convict labor at below-market rates. Described by some as “neo-slavery” this was a morally repugnant institution but one which benefited powerful interests. It lasted far longer than it should have, but eventually earned a well-deserved spot in the dustbin of history.

The parallel here is not to public schooling per se but rather to ZIP code assignment. ZIP code assignment to schools effectively reduces children into indentured funding units. Powerful interests in today’s society financially benefit reducing children into indentured funding units. Like southern plantation owners and railroad magnates from a bygone era, they are not going to let peonage go away without a fight.

The Tribune piece can be understood in this light: a struggle for a more humane system, one that acknowledges and respects the need for pluralism and variety in schooling. My heart sang when the story of these heroic women included a description of the aid they had received from their fellows in Arizona:

"In Arizona, 40 Black moms gathered in 2016 with the same worries for their children, ready to dismantle what they call the school-to-prison pipeline. Their kids were bullied in school and did not feel supported by the teachers. The moms started by pushing school districts to form a re-entry-after-suspension plan and find alternatives to suspension as a disciplinary measure.

By 2021, they had opened their own microschool, also known as outsourced home schooling. The Arizona microschools depend on the state’s education savings account program for sustainability.

“The public school system that was in place was not doing what it was supposed to do. Our children were not reaping the benefits,” said Janelle Wood, the founder of Black Mothers Forum in Arizona. “And so we needed a tool to help us fuel our vehicle of the microschool in order for us to grow."

Choice provides families with the tools to chart their own path and determine their own future. It gives teachers like those featured in the Tribune the opportunity to create their own schools. Choice gives families the opportunity to find a school that is a good fit for their children. Texas legislators must decide between clinging to an antiquated past or embracing a brighter future.

Just what is a microschool? The Christian Science Monitor takes a thorough and balanced look at the growing movement.

Ask a dozen microschool leaders to describe their schools, and you’ll likely receive a dozen slightly different responses:

Montessori-inspired, nature-focused, project-based, faith-oriented, child-led, or some combination of other attributes. They may exist independently, as part of a provider network, or in partnership with another entity such as an employer or a faith organization. Their schedules vary, too. Some follow a typical academic calendar, while others operate year-round, and some allow students to attend part time.

In other words, there is no one-size-fits-all definition for microschools. But, in general, they’re intentionally small learning environments. They often serve fewer than 30 students total and operate as learning centers to support home-schooled students or as accredited or unaccredited private schools. Their exact designations differ based on state laws.

To that description, I'd just add one more layer of nuance: Many microschools operate in partnership with public schools, for example, by sub-contracting with districts or charter schools, or as affiliates of longstanding private education institutions, like the microschools operated by the Catholic Diocese of Los Angeles.

Their diverse missions and configurations share something in common: divergence from the norm in public education. I have yet to encounter a microschool whose founders describe their work in terms that in any way resemble: We offer conventional schooling, only better.

Microschools break from convention, by design. Their breaks from convention could relate to content (they may offer religious instruction that isn't possible in public schools), pedagogy (they might embrace classical education or student-led learning), the identities of students they aim to serve (as in the case of the Black Mothers Forum in Arizona), or the structure of schooling (by bringing together students of different ages or offering hybrid and part-time schedules).

This is where their small size matters. A microschool can make bold and specific choices about what it offers, because it often only needs to attract a small number of like-minded students and educators. This allows microschools to exist in communities that could not possibly muster the numbers to sustain traditionally sized schools aligned to their philosophy or value proposition.

In rural New Hampshire towns where it wouldn't be economical for a conventional private or charter school to offer an alternative to existing public schools, 10 students can sign up with a learning guide to form a Prenda microschool. Under Prenda's flexible, student-led instructional philosophy, they need not even be exactly the same age. The Black Mothers Forum operates a network of microschools in Greater Phoenix, where just 7% of public-school students are Black—less than half the percentage in public schools nationally. These and countless other examples are able to offer particular groups of students something truly different, without having to worry about sanding down the edges of their identity to attract a critical mass.

To be sure, some microschools could grow to the point that "micro" becomes a misnomer. Some could operate "schools" that serve groups of students in multiple locations, or simply enroll enough students that they rival the size of a more conventional learning environment.

Thanks to their ability to operate at a small scale, to bring students together in ways that defy the conventions of age-based grading, and sometimes to blur the lines between schooling and homeschooling, microschools have the potential to enable a new level of pluralism and diversity in education.

On this episode, Ladner speaks with the founder of a Phoenix-based organization dedicated to erasing systemic inequities and ending the “school-to-prison” pipeline for Black children.

On this episode, Ladner speaks with the founder of a Phoenix-based organization dedicated to erasing systemic inequities and ending the “school-to-prison” pipeline for Black children.

In partnership with the Arizona-based microschool organization Prenda, Black Mothers Forum facilitates seven microschools, each serving 10 students or less in the Phoenix area. The group aims to grow to as many as 50 microschools.

Ladner and Wood discuss the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated inequities for Black children, what led Black Mothers Forum to explore microschooling, and enthusiastic parent response to the microschool environment, which they say allows their children to thrive in a safe space.

"Most children in traditional settings are told what they're doing that day. They may not feel like doing it that way and might not do as well. We’ve found our children excel when they get a chance to choose what part of their goals they want to fulfill that particular day, and they do it well."

EPISODE DETAILS:

Editor’s note: Christina Foster of Phoenix, a long-time education choice advocate, pleads in this commentary for the passage of Arizona House Bill 2427. Foster’s daughter transferred this year to a micro-school located at the Black Mothers Forum, which partners with Prenda’s Micro-school program to create safe and supportive learning environments.

Editor’s note: Christina Foster of Phoenix, a long-time education choice advocate, pleads in this commentary for the passage of Arizona House Bill 2427. Foster’s daughter transferred this year to a micro-school located at the Black Mothers Forum, which partners with Prenda’s Micro-school program to create safe and supportive learning environments.

Arizona is a national leader when it comes to diverse school options. Having a statewide culture that embraces creativity and innovation in K-12 public education is critical for creating learning environments that allow every child to feel safe and thrive.

For more than 40 years, the state has had an open enrollment option. As with any program or law, modernization is the key to ensuring the needs of a community are met. While the state has a robust public charter school system and expansive open enrollment for public district schools, modifications are needed so that every family has access to the public school of its choice.

For decades, attendance zones have intentionally blocked students of color and low-income students from the best public schools. Enrollment processes like “first come, first served” disenfranchise the working poor who cannot afford to miss days of work to wait in line.

Unfortunately, many parents in low-income communities find the current system burdensome and confusing. It often is unclear to parents at what time of the year they are allowed to request enrollment and when they will know if their child is accepted. Also, some schools require parents to complete long applications and paperwork disclosing protected information – such as a student’s disability – before their children have even been enrolled.

The pandemic crisis has shed light on the need to enhance the open enrollment opportunity. Not every school is right for every child, and every parent should have the opportunity to determine what is best for his or her child.

Parents and school leaders are making their voices heard in the Arizona Legislature, advocating for changes to the current system that will equal the playing field. Families of color are frustrated with the sentiment that we are forced to attend our neighborhood school even when it is not the best fit for our children.

House Bill 2427 will make long overdue changes to Arizona’s open enrollment system to assist families searching for the best public school for their children.

We can do better, and we must do better, so every child has access to a safe, high quality classroom.