Available to All has released a new study called The Broken Promise of Brown v Board of Ed A 50-State Report on Legal Discrimination in Public School Admissions. This May will mark the 70th anniversary of Brown vs. Board, the landmark United States Supreme Court case which struck down segregating schools by race.

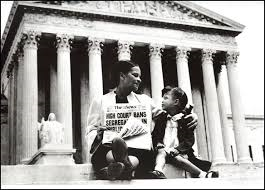

Linda Brown, whose family was among the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education

Many decades later, all is not well:

Seven decades after Brown, low-income children—many of them children of color—are still systematically excluded from the very best public schools. The brutal truth is this: In 2024, Linda Brown wouldnʼt be turned away from a coveted public school because of her race, but itʼs likely she would still be turned away. And itʼs all perfectly legal.

The study details how district boundaries deny opportunities to attend high demand public schools, and the relative strengths and (mostly) weaknesses of district open enrollment in all 50 states. The state of district open enrollment is not pretty, and amazingly many public magnet schools seem even worse:

Believe it or not, many coveted magnet schools give enrollment preferences to wealthy families, trying to lure them away from their high-quality zoned schools. It is one of the great ironies of public education that magnet schools, created to reduce segregation and increase opportunities for low-income children of color, often now intentionally put those same children at a disadvantage. Linda Brown, in other words, might be legally turned away from a public school in 2024 because her family doesnʼt make enough money.

The study contains a how-to manual for improving open enrollment laws in the states- and there is a huge amount of room for improvement even in what we think of as relatively open enrollment friendly states. Many states for example still grant by statute a veto over to open-enrollment transfers to resident districts as if students were feudal serfs.

The study is well worth your time to examine, and I will only add that the incentives faced by districts are probably at least as important as the laws governing them. As Clayton Christensen noted, organizations cannot disrupt themselves, so laws allowing educators to open new private and public schools can create incentives for high-demand district schools to lower their drawbridges.

Nearly 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education rewrote the rules of American K-12 education, pundits and academics are still debating its legacy. And despite nearly universal agreement over the shame and damage done by segregation and resistance to integration, some refuse to reflect deeply on the very flaws of the public institutions and policies they support today.

Nearly 70 years after Brown v. Board of Education rewrote the rules of American K-12 education, pundits and academics are still debating its legacy. And despite nearly universal agreement over the shame and damage done by segregation and resistance to integration, some refuse to reflect deeply on the very flaws of the public institutions and policies they support today.

Leslie T. Fenwick, dean emeritus of the Howard University School of Education detailed the more than two-decade struggle to integrate America’s public schools post-Brown and the many years of fallout that occurred following the loss of what she claims to be 100,000 Black educators at the time.

Fenwick argues that modern post-Brown initiatives aimed at disfranchising Black teachers and students continue to this day. Even while enumerating the ills created by America’s racially segregated public school system, she oddly points at modern reform policies and institutions that are better serving Black students and teachers today than the district-run public schools she prefers.

Fenwick notes that the white dominated public school districts not only resisted racial integration for more than two decades, but also fired many highly qualified Black teachers to give jobs to white ones. According to her calculations, this led to a $1 billion to $2 billion loss in salaries for Black educators and a brain drain among educated and experienced teachers in Black schools.

These losses are still felt today.

Indeed, the percentage of Black teachers has declined overall, falling from 8.1% 1971 to 6.7% today. (It is worth a side note: the percentage of other non-white educators has risen from 3.6% in 1971 to about 14% of the teacher population by 2017-18). Despite there being a majority-minority student population today, most teachers remain white. According to the latest data from the Digest of Education Statistics, white teachers still make up a majority of teachers (79.3%) compared to Black (6.7%), Hispanic (9.3%), Asian (2.1%) and mixed-race (1.7%).

But the target of Fenwick’s ire isn’t the centralized public school system, whose rules and policies are enforced by the whims of whatever political majority is in power at the time. Instead, Fenwick pivots to target alternative teacher certifications, charter schools and school vouchers as “post-Brown policies” akin to the ones used to resist racial integration in the 1950s, 60s and 70s.

However, these modern programs provide better outcomes for Black students and teachers than the district-run public schools she prefers.

Alternative teacher certification programs are designed to help people with college degrees enter the teaching profession without having to re-enter college for additional degree obtainment. Black professionals wishing to enter the teaching workforce make up 13% of the alternative certification track compared to just 5% for the traditional education bachelor’s degree route. In other words, alternative certification may be a more effective way to get educated Black teachers into classrooms.

Charter schools not only educate a proportionally larger body of Black students than traditional public schools, but they educate those students better and are more likely to match a Black student with a Black teacher.

Modern school voucher programs also are an odd target, considering the first modern voucher programs in Milwaukee and Florida both aimed scholarships at low-income Black students. In fact, Florida’s Opportunity Scholarship student population was nearly 100% Black when the teachers union sued to eliminate the program.

Today, Florida’s income-based private school choice programs are 73% non-white. It also is worth noting that students on these scholarships are more likely to attend and graduate college with a bachelor’s degree, a critical factor in producing new teachers.

Fenwick is clearly aware of the flaws inherit in a politically controlled public school system. She writes:

“With curriculums and textbooks nearly all-white in authorship, content and imagery; and, with district leadership, funding, and policy levers controlled almost exclusively by white officials.”

But instead of offering solutions to the current flaws, she condemns education reform and offers instead an alternate history where Black teachers were never fired, resulting in a perfectly functioning public school system today.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board decision and the 1968 conflict between the white New York City teachers union and the Black Ocean Hill-Brownsville community were historic events. Together they helped make well-intentioned white paternalism the primary way public education has related to Black students and their families for the last 50-plus years.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board decision and the 1968 conflict between the white New York City teachers union and the Black Ocean Hill-Brownsville community were historic events. Together they helped make well-intentioned white paternalism the primary way public education has related to Black students and their families for the last 50-plus years.

Black families and their children have not been well served by this paternalism. It is time we replace white paternalism with Black empowerment.

The Brown decision did not empower Black families to have more control over how their children are educated. Instead, it further empowered white paternalism. The court told white school boards to stop racially segregating their school buildings in the hope that Black children would benefit from sitting next to white children. Most white school boards delayed as long as possible, but by the late-1960s they were under intense legal pressure to desegregate.

In response to this ongoing legal pressure and the political opposition of white families to forced bussing, districts began implementing magnet programs in the late 1970s and early ’80s to encourage white families to voluntarily desegregate their school buildings. Magnet schools are high-quality, well-funded specialized programs that districts create in Black community schools to attract white students.

Magnet schools are a win-win solution for white families and school districts. Advantaged white children receive even more advantages, and white school boards have numbers showing their school buildings are integrated. The only losers are Black students who seldom benefit from these high-quality programs while being used as statistical props by school districts.

(Full disclosure: I helped start Florida’s first International Baccalaureate program in 1984, which was a magnet program designed to appease politically influential white families while satisfying a federal desegregation order.)

White liberal families are especially attracted to magnet programs because they enable these families to tell their likeminded friends that their children are enrolled in integrated public schools. What usually goes unsaid is that within these integrated buildings their children are attending elite programs with entrance requirements that often lead to racial and economic segregation.

White paternalism and Black disempowerment were further enhanced by a political confrontation in New York City. In 1968, all New York City schools were controlled by a Central School Board that was uninterested in integrating the school system. As their frustration grew, Ocean Hill- Brownsville families and community leaders decided the best way to meet their children’s needs was to assert greater control over their local schools. The city’s teachers union saw decentralizing control of the city’s schools as an existential threat to their business model, which requires a centralized, command-and-control management system to enable collective bargaining.

The union went on strike for 36 days, crushed the Black community’s struggle for self-determination, and reaffirmed some enduring precedents. Public education would continue to be controlled by white power, Black communities would continue to be disempowered, and white power would make good-faith efforts to educate Black children, provided all aspects of white privilege were protected—particularly relating to teachers unions.

(Full disclosure: I am the former president of two local teachers unions.)

The disempowerment of Black families and their reliance on white paternalism to meet their children’s learning needs is still the dominant reality in public education today. And it is still the prevailing philosophy of my political party (i.e., Democrats). But there are hopeful signs that enlightened progress may be possible.

Serial and The New York Times recently published a five-episode podcast, titled “Nice White Parents,” that documents the inability of well-intentioned white paternalism to improve the schooling of Black children. In a follow-up piece called “How White Progressives Undermine School Integration,” the Times interviewed progressives about the appropriateness of the current racial and economic power relationships in public education.

Times reporter Eliza Shapiro introduced these interviews by stating that, “across America, desegregation has never been tried at scale, partly because of resistance from white liberals.” Shapiro also stated the importance of focusing “on empowering Black and Latino parents who have so often been left out of the debate about their own children’s educations.”

Here are some representative quotes from Shapiro’s interviews.

Chana Joffe-Walt, the lead reporter on the Nice White Parents series: “I walked through the history of a school where integration has been invoked over and over again as a virtue, and used as a reason to pursue policies and programs that benefit white parents, that benefit advantaged parents — and that didn’t actually shift power within the school….it is more important to talk about race and power in more explicit terms, and to talk about this history.”

Sonya Douglass Horsford, professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College: “The focus needs to be shifting, for those who are focused on justice, from equity to emancipation. That means for students of color, for immigrant students, for others who have been marginalized in the U.S. school system, to recognize the system that they’re in and to begin to think about ways to liberate themselves from that.”

Richard Buery, president of a charter school network: “In this city, it’s always integration on white people’s terms…Racial oppression is obviously not new, including in schools, which were in so many ways designed to be the instruments of oppression.”

That the New York Times is willing to publish comments questioning the ability of white liberal paternalism to delivery greater equity and excellence in public education is a hopeful sign. But the paternalistic relationship between Black families and public education that the Brown decision and the 1968 New York City teachers’ strike further institutionalized has served white families and teacher unions well and will be difficult to change.

Replacing systemic white paternalism with the empowering of Black families is a necessary but not sufficient condition for improving Black student achievement. We also need to implement the support systems these families need to exercise this empowerment as effectively as possible. This is an area where well-intentioned white liberalism can be helpful. Liberation, empowerment, self-determination, and appropriate support is a formula that will help public education achieve more equity and excellence.

One of the prevailing criticisms of charter schools and other education choice programs is that they contribute to the re-segregation of public schools, evoking the malevolent days of “separate but equal.” An Associated Press analysis in December asserted that “charters are vastly over-represented among schools where minorities study in the most extreme racial isolation.”

In Minnesota, a lawsuit winding its way through the court system accuses the state of enabling racial segregation in the Twin Cities metro area in part by allowing charter schools.

The issue arose in a recent forum for Pinellas County (Florida) School Board candidates. The moderator asked candidates whether they support racially and economically integrated schools, “considering research that school choice deepens segregation,” the Tampa Bay Times reported.

That last point is arguable. Corey DeAngelis of the libertarian Cato Institute has reported that none of the eight “rigorous empirical” studies he found on the subject indicated that vouchers increased racial segregation (in fact, seven of them showed that such programs improve racial integration).

Even accepting the premise, it’s worth noting that it results not from government-enforced segregation, which the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka struck down as being unconstitutional, but rather from parental choice. Those choices are made by families black and white, many of whom give higher priority to educational factors other than a school’s racial balance.

For example, with regard to the Minnesota lawsuit, Friendship Academy of Fine Arts is a K-6 charter school in Minneapolis that serves a student population that’s 96 percent African-American and 85 percent low-income. In 2016 it was named a National Blue Ribbon School, one of only five schools in the state to receive that honor.

Why should government prohibit parents from exercising that choice, forcing them to attend an assigned school that may not meet their needs or standards? There’s no justification for cases like that of Edmund Lee, the Missouri third-grader whom a state law prevented from returning to his charter school simply because he’s black.

Keeping families in their neighborhood schools is unlikely to rectify the situation anyway. The de jure segregation of Jim Crow has been replaced by de facto segregation that is the result of deeply rooted socio-economic conditions. Affluent families – often white -- have more options available to them; they can afford to move to nice neighborhoods with good public schools. Poor families – often black -- have a much more difficult time escaping low-income areas with schools that can’t adequately fulfill their demands.

Integration can be a worthy end, for educational and social reasons. Data from the National Assessment for Educational Progress indicates that students in diverse schools have superior academic outcomes than their peers of similar backgrounds who attend high-poverty schools.

However, there are ways to achieve that other than by government mandate, that preserve parental choice and expand opportunities for all.

For instance, more school districts are using weighted admissions systems in their school choice programs that prioritize students based on their family incomes, rather than race.

Others are addressing the challenge from a different vantage point, by breaking away from routine thinking.

Writing in The Providence Journal last week, Jeremy Chiappetta, the executive director and founder of Blackstone Valley Prep Academy, a network of charter schools in Rhode Island, suggested changing the way we define neighborhood schools.

Blackstone Prep draws students from four different areas -- two higher-income communities and two lower-income ones -- which has resulted in a diverse student population. If the school served just any one of the communities, it would be segregated.

He also cites Citizens of the World Charter School Mar Vista in Los Angeles, which targets three different zip codes encompassing seven square miles, whereas the typical school zone in the area is one square mile.

Chiappetta writes:

“The reality is, charter schools that draw students from more diverse populations will have more diversity because they are redefining what it means to be a neighborhood school. Redefining neighborhoods is one of the proven ways to integrate and champion diversity in schools.”

Blackstone Prep and Citizens of the World are members of the Diverse Charter Schools Coalition, which promotes diversity through recruitment, admissions policies, and school design.

A home address should not determine the quality of a child’s education. Nor should the quest for a numerical ideal come at the expense of empowering families to secure the best educational environment for their kids. However, choice and integration also don’t have to be mutually exclusive goals.

Brown v. Board of Education opened many doors of opportunity, but too many remain closed. School choice can open some more.

Longtime school choice advocate Howard Fuller and a high-profile panel will reflect on that theme tonight at a National School Choice Week event in South Florida. To watch it live, just come back and view it here at 6:15 p.m.

You can also keep tabs via Twitter @redefinedonline. Search for #SCW and #FLschoolchoice.

In the meantime, here are some more thoughts on the links between Brown v. Board and school choice from some of the panelists you'll be hearing from.

T. Willard Fair, former chairman, Florida Board of Education; president, Urban League of Greater Miami:

While we were victorious in fighting for school choice nearly 60 years ago, the struggle continues. Choice is still an issue for many low-income children who come from the wrong side of the tracks. The Urban League of Greater Miami has made education and school choice the focal point of its work for over 50 years because access to quality education is still one of the most pressing civil rights issues of our times. This is not to sound somber or overly critical of the great strides we have made with Brown vs. Board of Education. However, we cannot be ignorant to believe that the victory of 60 years ago assuaged all of our “Black or Brown” educational issues. The need to access quality education is still alive and evident in Florida with more than 60 percent of Black children reading below grade level. (more…)

by Wendy Howard

While working on our upcoming National School Choice Week event that will showcase the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision I noticed some similar behaviors between those who opposed desegregation in that landmark case and the behaviors of those who oppose school choice today.

Anger, hatred, name calling. Shall I go on? People can be very cruel when they feel threatened or disagree.

Growing up in Iowa, I was never subjected to racism or real hatred. There were nice people and there were mean people. Color was never a factor in determining who my friends were. At times, best friends would wind up duking it out at the bus stop and then be best friends again the next day. (Yes, I was one of those who did that.)

Our parents taught us that if you didn’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything at all. If you do something, do your very best or don’t bother doing it all. Most importantly, always – always – do the right thing.

Many things have changed since I grew up in Iowa, but some things haven’t. Parents still value education. Parents still know what’s best for their children.

Over the years, my daughter Jessica has accessed several schooling options. She is currently in a charter school. But back in 2009, when she was seven years old, she began a petition to remove the requirement that students be enrolled in public school for at least one year before they can enroll in a district virtual education program. Many who opposed what Jessica was doing attacked me. They even attacked her! That was my first taste of what the real world was like when dealing with what I later realized was very controversial.

Charles Glenn: it's time for a ruling on par with Brown v. Board of Education to end legalized discrimination in education on the basis of religion.

New Hampshire joined other states in adopting a tuition tax credit program in 2012; now this has been partially blocked by a ruling that illustrates how urgently the United States needs a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court doing, for legalized discrimination on the basis of religion, what Brown v. Board of Education did for legalized discrimination on the basis of race. In fact, the two institutional forms of bigotry – one adopted by Southern Democrats, the other by Northern Republicans – are intertwined historically.

The 2012 New Hampshire law allows businesses to claim credits against business taxes owed equal to 85 percent of amounts they donate to state-designated "scholarship organizations.” The organizations then award scholarships up to $2,500 to attend non-public schools or out-of-district public schools, or to defray costs of home schooling.

Opponents charge that this violates Article 83 of the state constitution, which stipulates “no money raised by taxation shall ever be granted or applied for the use of the schools of institutions of any religious sect or denomination.”

After a one-day hearing and more than six weeks of pondering, Judge John M. Lewis ruled June 17 that funds raised through tax credits were public funds (even though they had never been in government coffers), and could not be used for scholarships to religious schools. This left the door open for their use for scholarships for non-religious schools.

State Rep. Bill O’Brien, who had been House Speaker when the law was enacted, told the Manchester Union-Leader the ruling “does not address why it is permissible for the state to allow tax breaks for religious organizations through college scholarships, but it is not permissible when it's a tax credit of this nature.”

According to the Union-Leader, “Charles Arlinghaus of the Josiah Bartlett Center for Public Policy said, ‘The final decision in this case was always going to come from the Supreme Court, which I'm sure will uphold the law. No education tax credit has ever been struck down by a Supreme Court in any state. This ruling is particularly odd. The entire program is fine unless a parent by their own choice chooses a religious school. By this logic a program is illegal if neutral and only legal if actively hostile to religion. That's absurd and I trust the Supreme Court will find it so.’"

Whatever the results of the appeal, it is a timely reminder of the need for a decision at the highest level to undo the lingering effects of religious discrimination in the American legal system. (more…)

by Gloria Romero

Between fundraisers, President Obama touched down in La Paz, Calif., recently to dedicate the home of Cesar Chavez, the late founder and leader of the United Farmworkers of America, as a historic monument.

Even I – an Obama supporter – recognized the obvious political timing of this event and the reaching out for Latino votes.

But I applaud the dedication, knowing that millions of Americans will visit the new historic site and learn not only about Cesar Chavez, but that California is home to one-third of the nation's migrant schoolchildren.

But we need more than just naming monuments. Indeed, we have a habit of naming schools after civil rights legends. But should a school that bears such a name also be among our state's chronically lowest-performing schools?

Last May, the Navy launched a new cargo ship, the USNS Cesar Chavez. What reaction would there be if that ship had sunk on its maiden voyage? Would we tolerate the drowning of its crew members? Surely, there would be an immediate call for a commission to "get to the roots" of this tragedy.

Yet, we allow schools named after heroic leaders to sink, year after year. Our students "drown" in chronically underperforming schools. Where are the inquiries?

This question is particularly relevant as we await release of California's Department of Education's List of 1,000 chronically underperforming schools.

This compilation is based on a law I wrote that mandated giving parents access to these "watch lists," which previously were compiled by bureaucrats and then just left on a shelf in Sacramento. The idea behind the law was to spotlight underperforming schools, to begin their transformation with parental knowledge and participation.

There are some 35 California schools named after Cesar Chavez. Almost all are identified as "Program Improvement" (PI) schools – which is a bureaucratic label meaning "failing." Tens of thousands of students are "drowning" in these chronically underperforming schools. No whistles are blown. We just step back and watch them sink; and we also seem to blame the students for the educational equivalent of not knowing how to swim.

One school on this list – and named for Cesar Chavez – is located in Santa Ana, not too far from the school involved in the historic Mendez et al. v. Westminster 1946 federal court case that challenged racial segregation in California. This landmark case became the precursor to Brown vs. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision barring racial segregation in schools.

Our public education system was forever changed with that decision. Now, a "Chavez" school in the same county as this historic site languishes on a "watch list" year after year.

In Northern California's Hayward Unified, Cesar Chavez Middle School has been on PI for more than 10 years.

In the Central Valley, Parlier's Cesar Chavez Elementary – not far from the newly dedicated Chavez national monument – first went on the watch list in 1998. Fourteen years; that's longer than the entire elementary and secondary education shelf life of students in these schools.

As this year's annual list is released, we should make it a priority to turn around chronically failing schools. No school should be left to fail year after year – especially not one named for a hero.

P.S.: There is a school in South Los Angeles that's named for Barack Obama; it also languishes on that "watch list." One of President Obama's recent fundraisers was held within blocks of it.

This column first appeared in the Orange County Register. Image of Cesar Chavez from biography.com