The story: Students with disabilities and English language learners were poorly served before the pandemic and will need urgent, long-term help to recover from learning losses, according to a report from the Center for Reinventing Public Education.

The Arizona State University think tank released its annual State of the American Student report today, with a bit of good news but mostly bad news.

“Our bottom line is we’re more worried at this point than we thought,” said Robin Lake, the center’s executive director. “COVID may have left an indelible mark if we don’t shift course.”

The good: Students are bouncing back in some areas. The average student has recovered about a third of their pandemic-era learning losses in math and a quarter in reading.

States and districts nationwide have implemented measures like tutoring, high-quality curricula, and extended learning time, and more school systems are making these strategies permanent. Florida, which offers the New Worlds Scholarship for district students struggling in reading and math, is on a list of states lauded for providing state-funding for parent-directed tutoring.

Rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness of tutoring at helping students catch up.

Rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness of tutoring at helping students catch up.

Education systems across the country – as well as students and families – are starting to recognize the value of flexibility. “As a result, more new, agile, and future-oriented schooling models are appearing.”

That includes microschools and other unconventional learning environments, which are multiplying to meet increasing parent demand.

The bad: These proven strategies aren’t reaching everyone. The recovery is slow and uneven. Younger students are still falling behind. Achievement gaps are also widening with lower-income districts reporting slower recoveries. And the positive studies that show tutoring’s massive boosts to student learning tended to operate on a small scale. Making high-quality academic recovery accessible to every student remains an unmet challenge.

Districts face “gale-force headwinds,” including low teacher morale, student mental health issues, chronic absenteeism, and declining enrollment.

The ugly: The report singled out services to vulnerable student populations for a special warning. The report said this group, poorly served before the first COVID-19 infection, suffered the most. Evidence can be found in skyrocketing absentee rates and academic declines for English language learners.

Special education referrals also reached an all-time high, with 7.5 million receiving services in 2022-23. The report attributed some of this to the pandemic’s effects on young children, especially those in kindergarten who were babies at the pandemic’s onset, but other factors, such as improved identification techniques and reduced social stigma around disability, are also at play.

In short, school systems face larger numbers of students requiring individualized support than ever before.

‘Heart-wrenching struggles’: While some families adapted well, most parents reported difficulty getting services for their children with unique needs. Schools were often insufficient in their outreach. Even the most proactive parents reported difficulty reaching school staff, the report said. Parents who were not native English speakers also had the additional burden of trying to teach in a language they were still learning.

“Many families said schools didn’t communicate often or well enough, and many parents felt blindsided when they found out just how far behind their child had fallen,” the report said.

Recommended fixes: Schools should improve parent communication. The report called for schools to “tear down the walls” by adding schedule flexibility to ensure students’ special education services don’t conflict with tutoring and adding more individual tutoring and small-group sessions. It said schools should also seek help from all available sources, including state leaders, advocates and philanthropists. Schools should also prioritize programs such as apprenticeships and dual enrollment to prepare students for life after graduation.

How policymakers can help: The report urged policymakers to gather deeper data on vulnerable populations so problems can be identified and corrected; provide parents with more accurate information about their children’s progress and offer state leaders a clearer picture of whether those furthest behind are making the progress they need, and help teachers use AI and other tech tools to engage students with unique needs.

The report urged policymakers to place more control in the hands of families by making them aware of their right to compensatory instruction or therapies for time missed during school closures. It also advocated offering parents the ability to choose their tutors at district expense.

The bottom line: Urgent efforts to improve education for students with exceptional needs will benefit all students, the report said. “There can be no excuse for failing to adopt them on a large scale. National, state, and local leadership must step up, provide targeted support, and hold institutions accountable.”

The Oceti Sakowin Educational Learning Center in Rapid City, South Dakota, is a Lakota-led microschool founded on Indigenous education principles and one of many educational environments recognized by The Canopy Project that are designing more equitable, student-centered experiences.

Where are the nation’s most innovative schools, and what are they doing that distinguishes them from the rest of the pack?

The Center for Reinventing Public Education and Transcend, two nonprofit organizations that support innovation in education, has put together The Canopy Project, a comprehensive public database of 251 schools that include district, charter and independent schools and microschools, all with core practices that raise the level of student-centered learning.

The project began in 2019 as a joint effort between Transcend and the Christensen Institute and is fueled by participation from hundreds of organizations and schools.

Last year’s report focused on the increasing number of programs developed for underserved populations who have historically been marginalized, such as students with disabilities. The year before that focused on creative ways of educating students during the challenges posed by the coronavirus pandemic.

A full report on this year’s project won’t be released until this fall, but analysts have already noted the following trends:

Other findings from the survey of leaders at these innovative schools show that three-quarters of them are focusing on developing a sense of community among students.

About 61% have designed advisories where groups of students meet regularly with adult advisers to set learning goals, reflect on progress, and build relationships. Some report increased mental health supports and train adults to recognize and respond to students who are impacted by traumatic stress, and pair students with an adult in school for regular individualized mentoring.

Almost two-thirds of schools reported the use of self-directed learning. This model allows students to set and pursue learning goals largely without adult supervision. About the same number reported an emphasis on practicality, with students learning topics and skills that directly relate to their lives and the world around them.

The survey also showed that 57% are offering learning beyond academics and college prep through career-focused opportunities such as practice job interviews and apprenticeships, while about half were providing learning though community service.

The report is searchable by state, by type of schools, by innovations employed or by student demographics. A user guide explains how to access and filter the data. The organizers hope it will be useful for policy makers, potential donors, and journalists, but most important, educators and entrepreneurs seeking to boost innovation.

“A redesigned school is far easier to imagine than implement. But too often, pessimism about the potential for change persists because educators, leaders, and families can’t picture what viable alternatives would look like,” wrote Chelsea Waite, senior researcher at CRPE and team leader on The Canopy Project, who introduced this year’s project in The 74.

“Amplifying the efforts of hundreds of schools designed to be equitable and student-centered is an exercise in optimism. Canopy offers hope that all kinds of schools can deliver on what students and families value most.”

Editor’s note: This commentary from Travis Pillow, editorial director at the Center for Reinventing Public Education, asks whether it’s time to redefine homeschooling amid the proliferation of new educational approaches blossoming in a COVID-19 world. It appeared Monday on CRPE’s website.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Travis Pillow, editorial director at the Center for Reinventing Public Education, asks whether it’s time to redefine homeschooling amid the proliferation of new educational approaches blossoming in a COVID-19 world. It appeared Monday on CRPE’s website.

One Saturday morning a few years ago, I was walking through an outdoor market in downtown St. Petersburg, Fla., where I lived at the time, when something piqued my professional curiosity.

A group of homeschool students were showing off art projects. I was trying to get a better feel for the various homeschool cooperatives that were cropping up around the state, so I struck up a conversation with some of the kids. One of them told me they homeschooled through Pinellas County Virtual School.

In other words, while I couldn't confirm every last detail of their schooling setup as described by a teenager, they may not technically have been homeschoolers. They could just as well have described themselves as full-time public school students taking online classes taught by certified teachers, employed by the Pinellas County school district and paid for by Florida taxpayers.

Perhaps the distinction only mattered in my policy-wonk mind. From their perspective, these families were homeschoolers. Their children took classes in their living rooms, with heavy involvement from their parents, who may have supplemented the official curriculum with art projects they displayed at the downtown market.

But now, as the nation grapples with an eighteen-months-and-counting experiment that thrust tens of millions of families into unplanned at-home learning, I'm starting to think that anyone who’s interested in understanding how this experiment could change public education for the long haul needs to grapple with this definitional issue.

It’s time to embrace an understanding of homeschooling that acknowledges the proliferation of new approaches—virtual schools, learning pods, microschools, “anytime, anywhere” learning, part-time schooling, and more—that blur current definitional boundaries and break down barriers between school, home, and community.

The growing mismatch between family behavior and institutional classification is skewing some efforts to make sense of families’ pandemic-era schooling choices. This spring, the U.S. Census Bureau released survey data suggesting that the share of families who homeschool their children jumped from more than 5% to just over 11% during the pandemic. Some headlines based on these survey data assert that the number of homeschoolers has doubled.

I’ve suspected something is fishy about these survey data. Families could be reporting their schooling situations to survey researchers the same way those families at the St. Petersburg market reported theirs to me: They count themselves as homeschoolers, when in fact they attend school at home, often virtually.

Recently, states have begun to release numbers of students and families actually participating in home education programs. Those numbers show historic jumps in homeschooling but also suggest the Census survey results may have overstated the homeschooling surge. For example, data released this month by the Florida Department of Education show the number of homeschooling students jumped more than 37,000 in a single year.

This 35.2% increase isn't based on parent surveys but an actual count of the students enrolled in home education programs registered with their local school district. It's a massive increase that could have real implications for public education. But it's not a doubling. And it's a far cry from the more than tripling of homeschooling that the Census surveys estimated in Florida.

Numbers trickling out of other states, such as the 48% increase reported in Virginia, tell a similar story.

The rise in self-reported homeschooling likely reflects these increases in homeschooling, strictly defined, combined with other trends—like the increase in the number of students who left their school districts for established, full-time online schools—that may feel like homeschooling to participating families but don’t meet the legal definition.

This is a trend we observed before the pandemic, which the disruptions of COVID-19 accelerated: The lines between schooling and homeschooling are getting fuzzier.

New line-blurring options emerged during the pandemic. Students attending the Southern Nevada Urban Micro Academy last year were attending a school by most common-sense definitions of the term, but to participate in their municipally funded pandemic learning community, they had to legally register as homeschoolers.

All this line-blurring is happening for a reason. Before the pandemic, families wanted more power to shape their children’s learning environments than the public education system allowed. During the pandemic, more families were desperate for alternatives to what their local schools offered and created new options for themselves that revealed new possibilities.

It’s still not clear how many of these choices will prove fleeting, and how many families will quickly return to their pre-pandemic schooling arrangements. Still, making line-blurring options accessible to all families and sustaining them beyond the pandemic for those who want them will require new approaches to funding and regulating education that won’t be simple to enact.

Understanding them will be essential if we want to build a public education system that is truly responsive to the needs of individual students.

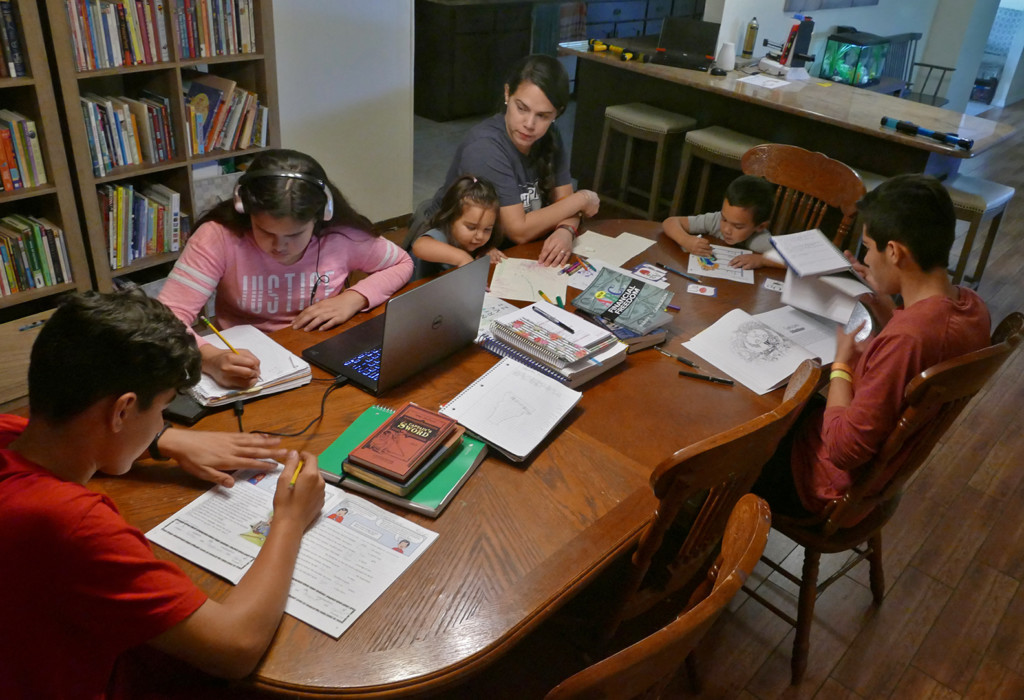

Convinced she could provide her children with all their educational needs, Evelyn Reyes of New Port Richey, Florida, began homeschooling her children eight years ago and realized she could combine education time with family time. PHOTO: Lance Rothstein

Editor’s note: This commentary was written expressly for redefinED by Matthew H. Lee, a graduate student in education policy at the University of Arkansas; Angela R. Watson, senior research fellow at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy; and redefinED guest blogger Patrick J. Wolf, distinguished professor of education policy and endowed chair at the University of Arkansas.

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive.” -- C.S. Lewis

What prompted Cevin Soling, Freedman-Martin fellow in journalism at Harvard’s Kennedy School, to choose this warning as he introduced an event at Harvard earlier this month?

The “tyranny sincerely exercised” is the presumptive ban against homeschooling that Harvard Law professor Elizabeth Bartholet recommends in her recent Arizona Law Review article, “Homeschooling: Parent Rights Absolutism vs. Child Rights to Education & Protection.”

Her proposed ban puts parents “ideologically committed to isolating their children” on trial and assumes their guilt for denying “their children any meaningful education” and subjecting their children to “terrifying physical and emotional abuse.” It shifts the burden of proof to the accused to “demonstrate they would provide a significantly superior education.”

What happened to a presumption of innocence before the law?

Far from Bartholet’s accusations, homeschooling is not a small, monolithic practice dominated “overwhelmingly” by conservative Christians. At any given time, homeschoolers make up roughly 3 percent of the school-age population, and one study published in the Peabody Journal of Education estimates that as many as 10 percent of all American students are homeschooled at some point during their academic careers.

A 2019 Center for Reinventing Public Education report finds the most rapidly growing homeschooling subgroups are people of color. Another report published in the Peabody Journal of Education noted that “The phenomenon of increasing black home education represents a radical transformative act of self-determination, the likes of which have not been witnessed since the 1960s and ‘70s.”

Meanwhile, National Center for Education Statistics data show that homeschool respondents are more concerned with the “environment of other schools” and “academic instruction” than they “desire to provide religious instruction.”

A presumptive ban against homeschooling denies at least two rights. First, it denies parents the right to govern the education of their child, proclaimed by the US Supreme Court to be their fundamental right in 1923 (Meyer v. Nebraska), 1925 (Pierce v. Society of Sisters), and 2000 (Troxel v. Granville). Second, by giving public officials the authority to conduct home visitations in homeschooling households and to forcibly enroll children in public schools against their parents’ wishes, it denies both parents and children the right to be secure in their persons and homes against unreasonable searches and seizures.

Let’s shift the burden of proof back to homeschooling’s accusers. Can they prove that public schooling delivers better academic results, strengthens democratic values and provides a surer guarantee against abuse than homeschooling?

Homeschooled children demonstrate academic outcomes equal to or better than their public-school counterparts. While we don’t know about academic outcomes for all homeschooled students, a 2010 report by Brian Ray finds that homeschoolers on average score between 15 to 30 percentage points above the national average. As for those who pursue a college education, a review by Gene Gloeckner and Paul Jones indicates that when differences are detected, homeschooled students have higher standardized test scores and college GPAs relative to their public school peers.

Homeschoolers also compare favorably to publicly schooled students on civic and democratic values. Research by Albert Cheng of the University of Arkansas finds homeschooling is associated with more political tolerance relative to public schooling. Indiana University’s Robert Kunzman reports a similar advantage in his 2009 book, “Write These Laws on Your Children: Inside the World of Conservative Christian Homeschooling.”

As for public school students, according to the 2018 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Civics Assessment, only 24 percent of U.S. eighth-graders perform at or above NAEP “Proficient” on civics.

Finally, even public schools cannot provide an absolute guarantee against abuse. In 2004, the US Department of Education estimated that one in 10 public school students will be sexually assaulted by a public school employee by the time they graduate. While abuse anywhere is unacceptable, a presumptive ban against homeschooling assumes parents are guilty of abusing their children until proven innocent while unrealistically assuming public school personnel are always innocent of such horrible transgressions. Unfortunately, they are not.

In delivering the opinion of the Supreme Court in the 1925 case Pierce v. Society of Sisters, Justice James McReynolds wrote, “The child is not the mere creature of the State; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.” Homeschooling may be the purest expression of families exercising this right and rising up to meet this high duty.

As courts have ruled repeatedly, when homeschooling is put on trial and given due process, a fair reading of the evidence gives us no choice but to emphatically declare, “Not guilty!”

Center for Reinventing Public Education

Center for Reinventing Public EducationThe Center for Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) is an education research and policy analysis think tank at the University of Washington, Bothell. The organization’s research finds statistical support for charter schools and for reforming the way public education is operated and funded.

Back in August, CRPE released a working paper on the impact of charter schools on student achievement. Its meta-analysis of high-quality studies found charters tend to have a small but positive impact on student achievement in math, but no additional impact in reading.

By the end of September, the National Education Policy Center released a review of CRPE’s analysis, calling CRPE’s conclusion “overstated” and “exaggerated” and concluding the report offers “little value for informing policy and practice.” (Readers of this blog may already be familiar with NEPC’s reflexive bias against charter school and school choice studies).

By the end of September, the National Education Policy Center released a review of CRPE’s analysis, calling CRPE’s conclusion “overstated” and “exaggerated” and concluding the report offers “little value for informing policy and practice.” (Readers of this blog may already be familiar with NEPC’s reflexive bias against charter school and school choice studies).

Well, get out your popcorn because CRPE just released a devastating counter-critique. CRPE accuses NEPC of quoting selectively, implying arguments not present, inaccurately presenting the research and several serious technical errors. In total, CRPE counts 26 errors within NEPC’s 9-page analysis.

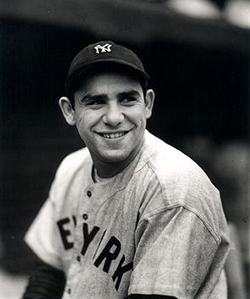

Yogi Berra once quipped, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially ones about the future.” While true, it doesn’t stop political pundits from attempting to predict the future based on (sometimes unreliable) exit poll data. Following the drubbing Democrats (and the once powerful education unions) received in the mid-terms, many of those pundits began wondering if education choice would lead minorities, especially African Americans, over to the Republican camp.

Yogi Berra once quipped, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially ones about the future.” While true, it doesn’t stop political pundits from attempting to predict the future based on (sometimes unreliable) exit poll data. Following the drubbing Democrats (and the once powerful education unions) received in the mid-terms, many of those pundits began wondering if education choice would lead minorities, especially African Americans, over to the Republican camp.

Just check out some of the speculation (Exhibit 1, Exhibit 2, and Exhibit 3) about how the school choice issue hurt Democrats and helped Republicans (at least in Florida).

But whether Republicans can use education and school choice to win over black voters isn’t the right question. The better, and more important, question is whether the school choice movement can finally win over more Democrats…

An advocacy group for charter school parents in Florida is warning its parents about widely circulating myths regarding Common Core State Standards. While the recent newsletter from Parents for Charter Schools doesn’t endorse Common Core, it does attempt to dispel what it says are a few misleading statements – and in tone, its language echoes that of Common Core supporters.

“There is so much misinformation out there and we all know that knowledge is power,” says the newsletter, which is posted on the group’s facebook page. “Some of the more common myths are that we will bring the standards down to the lowest common denominator. This (is) just not true. The standards will be brought up (to) the higher standards.”

“There is so much misinformation out there and we all know that knowledge is power,” says the newsletter, which is posted on the group’s facebook page. “Some of the more common myths are that we will bring the standards down to the lowest common denominator. This (is) just not true. The standards will be brought up (to) the higher standards.”

The charter school parent group’s statements are another intriguing tidbit in the battle over Common Core, which has fuzzed up traditional lines between education factions. It also further complicates, at least in Florida, a side skirmish over whether the standards will help or hurt school choice.

As we’ve reported before, many private schools in Florida are embracing Common Core as part of a parental engagement effort led by Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog. Many Catholic schools in Florida and beyond have also warmed to the standards, though with a faith-based twist and with more reticence recently as political heat over the standards has risen. (more…)

Charter school critics got a lot of mileage from a U.S. Government Accounting Office report last summer that found charter schools enrolled fewer students with disabilities than traditional public schools. But a new report (hat tip: EdWeek) offers even more reason why we should all take a more careful look before leaping to conclusions.

The Center for Reinventing Public Education found the numbers for middle and high schools in New York state were on par between the two sectors. And while fewer students with disabilities were enrolling in charter elementary schools, that didn't mean discrimination. Wrote the center:

The fact that only charter elementary schools systematically enroll lower proportions of students with disabilities than their district-run counterparts calls into question whether discrimination drives lower enrollment. There is no obvious reason to think that charter elementary leaders would be more likely to discriminate than charter middle and high school leaders. Indeed, the fact that state testing does not begin until the third grade suggests that elementary schools have arguably the weakest incentives to discriminate against students with disabilities. The grade-span differences highlight a need to examine what is different about the policies and practices of special education and the preferences of parents with students with disabilities at the elementary grades versus the upper grades. Many causes other than discrimination could be affecting enrollment.

It may be that charter schools are simply less likely to identify students as having disabilities that qualify them for special education in the first place, or that specialized preschool programs with designated district feeder schools lead parents to opt for the district school over the charter school. Or it may be that federally mandated district counseling for families of kids with disabilities creates opportunities for the district to encourage these families to stay in district-run schools, whereas non–special education students’ families never get such advice. None of these potential contributors to elementary level underenrollment in charter schools have been explored sufficiently, if at all.

The GAO report was written about widely, from the New York Times and Wall Street Journal to outlets in Florida. It'll be interesting to see what kind of coverage the new report gets.

Writing in Education Week, Paul T. Hill, the director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, says today's school funding arrangement developed haphazardly, a product of politics and advocacy, not design:

Simply put: Our current education finance system doesn't actually fund schools and certainly doesn't fund students. Rather, it pays for districtwide programs and staff positions. Much of it is locked into personnel contracts and salary schedules—and most of the rest is locked into bureaucratic routines. It's next to impossible to shift resources from established programs and flesh-and-blood workers into new uses like equipment, software, and remote instructional staffing. Yet to foster and maximize technology-based learning opportunities, we must find ways for public dollars to do just that—and to accompany kids to online providers chosen by their parents, teachers, or themselves.