It may seem a stretch to attempt a school choice angle for Labor Day weekend, given teachers unions are the snag to school choice expansion. But I’ll give it a shot.

The school choice advocates I know believe parents have a right to educate their children as they see fit, and that school choice levels the playing field so more parents can more fully exercise that right. I haven’t seen any survey results to be sure, but I can’t see any reason why union members, outside of teachers unions, would disagree.

Now and then, some unions have dared air that position publicly. A few years ago, an impressive list of unions in New York lined up for Gov. Cuomo’s proposal for tax credit scholarships. In the 1990s, the Teamsters in Pennsylvania went all in for vouchers. In the 1970s, the legendary Cesar Chavez backed a private “freedom school” in the farmworker town of Blythe, California – and foresaw an education system that was (once again) grounded in pluralism.

“Gradually,” Chavez said, “we’re going to see an awful lot of alternative schools to public education.”

Closer to home, hundreds of public school district employees in Florida, including many teachers, use private school choice scholarships for their children. At last count, more than 1,400 had secured a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, which are available to lower-income families (and administered by non-profits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Again, I don’t have hard data. But I know from talking to dozens of those parents that many are union members. Some had no idea about “controversy” with “vouchers.” They just knew the scholarships helped their children.

One of them, a bus driver, secured a scholarship after her daughter got into a fight in her district school and then, despite no other blemishes on her record, faced re-assignment to an alternative school for disruptive students. Another, a teacher, got a scholarship because her son, a former foster child, needed a smaller school with more structure and attention than his district school could give him. I don’t know any parent who wouldn’t sympathize with either mom.

Yet another scholarship parent was not just a teacher and union member, but a member of her union’s executive board. She said she valued school choice but, for obvious reasons, had to keep her views to herself. Luckily, she said, the issue of school choice never came up with her union because it had bigger fish to fry – like corralling better pay.

Sounds like the right priorities to me.

Happy Labor Day!

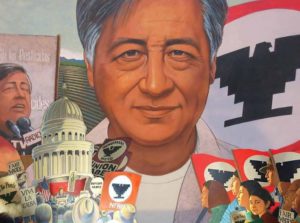

“Gradually,” Cesar Chavez predicted, “we’re going to see an awful lot of alternative schools to public education.” (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

Cesar Chavez, the iconic labor leader, would have been 90 years old today, and progressives, including teacher union leaders, are pausing to honor him. But few of them probably realize Chavez’s vision of a better world – the same vision that led him to organize the most abused workers, and battle the biggest corporations – included scenes of community empowerment from earlier chapters in the school choice movement.

Chavez was a steadfast supporter of Escuela de la Raza Unida, a forgotten “freedom school” in Blythe, Calif. that sprouted in 1972, in the wake of mass parental frustration with local public schools. Some of his comments about this school in particular, and public education more generally, can be found in this rough-cut documentary about the school’s creation.

“We know public education has not … been able to deal with the aspirations of the minority group person or, in our case, our kids who have been involved with the struggle for social betterment,” Chavez tells an interviewer at about the 7:30 mark in the video.

“The people who run the institutions want everybody to think the same way, and it’s impossible,” he continued at another point. “We have different likes and dislikes, and different ideals. Different motivations. And so I’m convinced more and more that the whole question of public education is more and more not meeting the needs of the people, particularly in the case of minority group people … “

The success of Escuela de la Raza Unida is proof, Chavez said, that truly community-led schools are needed – and can work.

“Gradually,” he predicted, “we’re going to see an awful lot of alternative schools to public education.” (more…)

Students picketed public schools in Blythe, Calif. when tensions between the Hispanic community and school district boiled over. The conflict led to the creation of a private school, Escuela de la Raza Unida, which remains in operation.

This is the latest post in our occasional series on the center-left roots of school choice.

If the American left had fully championed school choice decades ago, we may be celebrating what happened in 1972 in Blythe, Calif. as the spark of a movement.

That spring, the Mexican-American community’s frustration with the public school system boiled over, spurring creation of a scrappy “freedom school” that became Escuela de la Raza Unida, which still exists today.

This lost story from a remote desert town is steeped in the progressive politics of another era.

In Chicano Pride. In empowering the “poor.”

Even in Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers.

“We were ahead of the curve,” said Carmela Garnica, who has led the school with her husband, Rigoberto Garnica, since the beginning.

Hispanic support for school choice runs strong. But if there is anybody who has chronicled that history, even Hispanic school choice leaders are unaware. Perhaps the story of Escuela de la Raza Unida can inspire the deep dive that this subject deserves.

The school sprang from years of dissatisfaction. The fuse-lighter was an allegation that the principal of the public middle school in Blythe manhandled a female honor roll student, apparently for showing a politically provocative film to a Hispanic student group. But parents had complained about other issues for years. They wanted diversity in the nearly all-Anglo teaching corps. They wanted history lessons that acknowledged contributions of Native Americans and Mexican Americans.

Students picketed the public schools for weeks. In the meantime, the community rallied to create an on-the-fly school where everybody pitched in to teach, cook, clean – whatever they could do. Initially, they met at a local park, according to newspaper articles and “A Choice For Our Children,” a 1997 book by California school choice supporter Alan Bonsteel. At some point, the dissidents decided to rent space for classes, a tiny former post office that could hold 50 students.

They never left.

Escuela de la Raza Unida began as a K-12 private school, and Garnica says it would have preferred to stay that way. But California doesn’t have vouchers or tax credit scholarships, despite multiple attempts at the ballot, including this liberal-led campaign in the late 1970s. Over the years, the school had to shift its mission to best match community needs with available funding. (more…)

Expanding school choice could lead to innovative options for the children of farmworkers - perhaps mobile classrooms that allow the students to learn as they travel. (Image by An Errant Knight, from Wikimedia Commons.)

I’ve written before of an afternoon with Cesar Chavez at UFW headquarters on the edge of the California desert. The year was 1981, and there was strong hope of putting a school choice initiative on the ballot.

Chavez, his nephew and I spoke of empowering farm workers with an educational option. On the one hand, if they wished, they could continue to educate their children in a string of disconnected public schools located in diverse districts along the seasonal harvest path north. On the other, they could choose among public and private schools travelling in buses, either parked in coordination with the parents’ location, and/or actually operating in moving buses variously designed for the purpose of schooling.

Chavez was warm, receptive – and frustrated. His impediment was the annual $200,000 he received from Albert Shanker and the AFT. So he said, and I believed him. I suppose the AFT still protects its monopolies in similar ways. I see no legal impediment except, possibly, the anti-trust laws.

Peripatetic schools in buses? I think so.

Most of the mobile schoolhouses would teach only when parked in a location convenient to the parents’ current worksite. Whether the bus was equipped actually to provide education en route could be one element of choice for the parents. What would, I think, be the central advantages of either style are two: the convenience of location near the parent and continuity of atmosphere and substance – the same room, books, teachers – everything about the school itself – plus the settling confidence of the child in the parents’ proximity.

To this I would add in the reduction in systemic public costs made possible by liberating school districts from the expense and complexities of providing space and whatever other necessities – a teacher, or several – for a new gang each week or 10 days. It could be a relief to all concerned to be able to offer parents a school appropriate to their child’s age, and consistent in its milieu and message.

School reformers could seriously consider – as a potential reform to both policy and politics – the convening of well-publicized conferences to consider the question of the most promising forms of itinerant schools for farm workers’ children. So far as I know, they have yet to model and critique the potential variety of such novelties as tools of wise educational policy. (more…)

This is the latest post in our occasional series on the center-left roots of school choice.

More than 30 years ago, liberal activists working to get a revolutionary plan for school vouchers on the California ballot approached labor leader Cesar Chavez, according to one of those activists, Berkeley law Professor Jack Coons. The co-founder of the United Farm Workers (Si Se Puede!) told Coons he liked school choice, but as far as supporting it publicly, No se puede.

Doing so would put the teacher union’s generous financial support for his union at risk, he said.

Other evidence suggests Chavez wasn’t just politely telling a fellow traveler no. More on that in a sec. In the meantime, it’s worth noting the Chavez anecdote isn’t the only example of labor unions occasionally backing school choice or, in a few cases, outright distancing themselves from their teacher union brethren.

Consider:

To be sure, I’m not suggesting union alliances against choice are about to crumble, and I can’t pretend to know if extenuating circumstances led these unions to make a break. But I think it is fair to say these examples shed more light on the myth that only conservatives and libertarians see the value of having more educational options for kids. The Netherlands, a union-friendly nation, and a pretty liberal one at that, embraced one of the planet’s most complete systems of school choice a long time ago.

I also think it’s fair to suggest from these examples that teacher unions, like the NAACP, risk becoming increasingly isolated from traditional allies because of head-scratching positions that leave those allies on the outs with their kids.

In our back yard, more than 800 parents of students using tax credit scholarships in Florida work for public school districts, according to data from Step Up For Students.* Some of those parents are public school teachers. Some, in fact, are teacher union members. But because of the income eligibility requirements, I’d guess the majority are custodians, bus drivers and other blue-collar workers – workers represented by the likes of AFSCME and the SEIU.

If the Florida teacher union succeeds in its lawsuit to kill the scholarship program, some of its members may rejoice. But tens of thousands of parents, including hundreds in other labor unions, will be heartbroken. I can’t imagine how that would be good for solidarity.

Back to Cesar Chavez.

In the early 1970s, farm workers in Blythe, Calif. started their own on-a-shoestring private school because they were fed up with conditions in public schools. Parents met at the local United Farm Workers hall to get the ball rolling, as longtime choice advocate Alan Bonsteel notes in the 1997 book he co-authored, “A Choice for Our Children.” The father of the woman who would become the school’s director, Carmela Garnica, was a UFW organizer.

The Escuela de la Raza Unida became a community gem. Garnica, a Democrat, became a voucher proponent. Chavez became a frequent visitor.

Si se puede? For vouchers?

It’s not as farfetched as people think.

*Step Up For Students is a nonprofit that helps administer the state’s tax credit scholarship program. It also hosts this blog and pays my salary.

by Gloria Romero

Between fundraisers, President Obama touched down in La Paz, Calif., recently to dedicate the home of Cesar Chavez, the late founder and leader of the United Farmworkers of America, as a historic monument.

Even I – an Obama supporter – recognized the obvious political timing of this event and the reaching out for Latino votes.

But I applaud the dedication, knowing that millions of Americans will visit the new historic site and learn not only about Cesar Chavez, but that California is home to one-third of the nation's migrant schoolchildren.

But we need more than just naming monuments. Indeed, we have a habit of naming schools after civil rights legends. But should a school that bears such a name also be among our state's chronically lowest-performing schools?

Last May, the Navy launched a new cargo ship, the USNS Cesar Chavez. What reaction would there be if that ship had sunk on its maiden voyage? Would we tolerate the drowning of its crew members? Surely, there would be an immediate call for a commission to "get to the roots" of this tragedy.

Yet, we allow schools named after heroic leaders to sink, year after year. Our students "drown" in chronically underperforming schools. Where are the inquiries?

This question is particularly relevant as we await release of California's Department of Education's List of 1,000 chronically underperforming schools.

This compilation is based on a law I wrote that mandated giving parents access to these "watch lists," which previously were compiled by bureaucrats and then just left on a shelf in Sacramento. The idea behind the law was to spotlight underperforming schools, to begin their transformation with parental knowledge and participation.

There are some 35 California schools named after Cesar Chavez. Almost all are identified as "Program Improvement" (PI) schools – which is a bureaucratic label meaning "failing." Tens of thousands of students are "drowning" in these chronically underperforming schools. No whistles are blown. We just step back and watch them sink; and we also seem to blame the students for the educational equivalent of not knowing how to swim.

One school on this list – and named for Cesar Chavez – is located in Santa Ana, not too far from the school involved in the historic Mendez et al. v. Westminster 1946 federal court case that challenged racial segregation in California. This landmark case became the precursor to Brown vs. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision barring racial segregation in schools.

Our public education system was forever changed with that decision. Now, a "Chavez" school in the same county as this historic site languishes on a "watch list" year after year.

In Northern California's Hayward Unified, Cesar Chavez Middle School has been on PI for more than 10 years.

In the Central Valley, Parlier's Cesar Chavez Elementary – not far from the newly dedicated Chavez national monument – first went on the watch list in 1998. Fourteen years; that's longer than the entire elementary and secondary education shelf life of students in these schools.

As this year's annual list is released, we should make it a priority to turn around chronically failing schools. No school should be left to fail year after year – especially not one named for a hero.

P.S.: There is a school in South Los Angeles that's named for Barack Obama; it also languishes on that "watch list." One of President Obama's recent fundraisers was held within blocks of it.

This column first appeared in the Orange County Register. Image of Cesar Chavez from biography.com