Recent election outcomes offer a snapshot of what people really think about education reform, said John Podesta, chairman and founder of the Center for American Progress. And lawmakers, advocates and opponents of school reform should all take note.

Recent election outcomes offer a snapshot of what people really think about education reform, said John Podesta, chairman and founder of the Center for American Progress. And lawmakers, advocates and opponents of school reform should all take note.

This month’s stunner - the ousting of Indiana public schools chief Tony Bennett, who implemented many of the same reforms found in Florida – is proof enough that reform “is not yet on solid ground,’’ said Podesta, the keynote speaker Tuesday during the fifth annual Excellence in Action National Summit in Washington, D.C.

At the same time, he noted, there are plenty of signs of progress, including historic passage of a ballot initiative in Washington that paves the way for charter schools.

The common ground seems to be a desire to create a system that works for children, he said, and reformers should seize the moment.

“As the lines blur, the movement has to invest in collaboration … ,’’ said Podesta, a former White House chief of staff to President Bill Clinton and longtime policy adviser.

“I think complete division between unions and reform is not helpful,’’ he said. “We have to let this go.’’

He also said reformers can’t “steamroll’’ measures without educating the public. “Stop just focusing on your enemy and start shoring up your allies,’’ he said. (more…)

Students at six high-poverty schools in Memphis returned to class this month as the focus of an education reform project that's worthy of national attention. The schools are the first cluster in the “Achievement School District,” a Race To The Top-fueled vision headed by Chris Barbic, founder of the acclaimed YES Prep charter schools in Houston.

Students at six high-poverty schools in Memphis returned to class this month as the focus of an education reform project that's worthy of national attention. The schools are the first cluster in the “Achievement School District,” a Race To The Top-fueled vision headed by Chris Barbic, founder of the acclaimed YES Prep charter schools in Houston.

The district’s near-term goal – lifting schools in the bottom 5 percent statewide to the top 25 percent within five years – is as ambitious as YES Prep’s target of getting every graduate into a four-year college. Its big-picture goal is even more so: Showing the world that lessons learned from the highest-performing charter schools can turn around the lowest-performing traditional schools.

Barbic calls it Charter School 3.0.

“There’s an opportunity here to say, look, we’re not creating the charter school that’s going to be across the street from the public school and slowly bleed it to death. What we’re saying is, this is the neighborhood school,” Barbic said in the redefinED podcast below (the phone interview was conducted during the first week of school). “To me this is Charter School Version 3.0. – which is, you don’t get to pick the kids; the kids don’t get to pick you. If we really believe this works, we’re going to phase you in and you’re now the neighborhood school. And you got to work with all the kids … whatever kids show up with, you have to serve those kids.”

“If we can pull that off,” Barbic continued, “it’s going to make a huge statement that will hopefully accelerate things like this in your backyard and other places around the country.”

Schools like YES Prep and KIPP share many characteristics – high expectations, high-energy teachers, longer school days, more flexibility at the school and classroom level. And yet, despite a solid body of evidence that they’re making a big difference for low-income kids, they remain fairly rare. Barbic said that’s in part because it’s only been in the past three to five years that they’ve learned to replicate more rapidly. But now, folks inside traditional school systems are beginning to appreciate the benefits.

“You’re seeing things in Denver and things in Houston where there’s efforts being made by the district to try and take the practices of the best charters, the best charter organizations, and try to apply them in a larger system,” he said. “And I think what’s happening in New Orleans with the Recovery School District, what we’re hopefully going to be able to achieve here, is an opportunity to say, ‘Look, this works. And it works at scale, in a neighborhood school environment.’ ”

On a related note, Barbic talks about ASD's parent outreach efforts - which are extraordinary compared to traditional public schools. When teachers showed up for school in early July, buses took them to the communities where their students live. “We hit all the apartment complexes. We banged on doors,” he said. “We met (the parents) and we invited them to come out to a community picnic that we were having later that week.”

The response: “Cautious optimism.”

“They’ve met us halfway,” Barbic said. “Now it’s on us to perform and get some results.”

by Kelly Garcia

In early spring of my first year teaching at YES Prep West, a high-poverty charter school in Houston, my school director shocked me with a list. It contained the home addresses of more than 20 incoming students, and I had about three weeks to visit each one. The undertaking turned out to be massive – 30 hours, a couple tanks of gas, and a couple pit stops at McDonald’s to feed my student helpers.

Teacher visits to student homes are still rare. But in my case, it planted seeds for partnerships that helped my students succeed.

The first step was to call each family and request a meeting when the parents and incoming student were both available. I learned quickly that the language barrier was going to make this challenging. Most of the parents spoke only Spanish. With some conversational Spanish skills, I struggled through several calls, unsure of whether I had translated the meeting date correctly.

I weaved through Houston with another teacher in the passenger seat and two current students in the back. At each stop, we were offered a treat: tamarindo sodas, homemade tamales, even fresh tortillas. Families gathered with nervous excitement over the journey they were committing to. At most stops, my students guided the meeting, translating my words from English to Spanish. We explained what made YES Prep so special - that every student, faculty member and administrator is working towards ensuring that each student is accepted to a four-college upon high school graduation. We promised the incoming sixth graders and their families that we would work tirelessly toward that goal for all seven years. Just this short introduction was often enough to make some parents tear up.

Once the parents internalized the extent of their child’s journey, they were excited and motivated to commit to a list of responsibilities they had to agree to in order for their child to attend. This list wasn’t a breeze. The school had mandatory Saturday classes. It also required students who did not complete their homework to stay after 6 p.m. the next day to finish it. The parents would have to provide transportation even though many of them were working two jobs and caring for small children. And yet, I never met with a parent who did not sign off on their responsibilities list. Any cynic who says parents – especially low-income parents - don’t care about their child’s education has never been to one of these meetings. (more…)

Editor’s note: Kelly Garcia, who is interning this summer with Step Up For Students, began teaching middle school last year in the Hillsborough school district.

One of my favorite responsibilities as a teacher at the YES Prep West charter school in Houston was the requirement to take small groups of students on field trips of my choice twice each year.

One of my favorite responsibilities as a teacher at the YES Prep West charter school in Houston was the requirement to take small groups of students on field trips of my choice twice each year.

I fondly remember driving Ivan, Javier, Citlaly, Mercy and Frances to one of Houston’s most famous chocolate shops, The Chocolate Bar, where they indulged in gigantic pieces of chocolate cake and foot-long chocolate bars. These trips allowed me to expose my students to a piece of their home city that they had never experienced, and allowed them to show me a piece of themselves that I had never seen. The outings fueled my dedication to them.

Ninety-five percent of the students in the 10-school YES Prep system are Hispanic or African-American. Eighty percent are economically disadvantaged. And yet last month, YES Prep won the first-ever Broad Prize for public charter schools with the best academic performance.

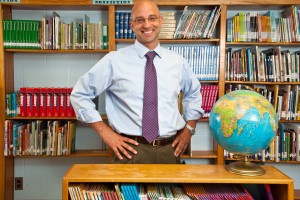

I was not surprised. I was fortunate to have launched my career in education as a founding teacher at YES Prep West, then a brand-new school in the YES chain. (That's me and my class in the photo.) Here are some of the ways its system is different from traditional public schools – and, in my view, more successful.

Choosing the right people. YES has perfected the art of choosing the right people to put in their classrooms. In part because of the system’s reputation for success, thousands of applicants apply each year for a small number of teaching positions.

Applicants are weeded out by phone interviews with instructional leaders from various campuses, and by a sample lesson they teach to actual YES Prep students. School directors often invite the students to weigh in with their impression of a potential teacher, too. By the end of the application process, school leaders are left with high-caliber, hard-working, mission-driven people. YES teachers are committed to working incredibly long hours (usually 12-hour days without a true lunch break), answering cell phones in the evening to help students with homework, teaching Saturday school at least once a month and even conducting home visits for incoming students. (more…)