For we who grew up tall and proud

In the shadow of the mushroom cloud

Convinced our voices can't be heard

We just want to scream it louder and louder and louder

— Queen, Hammer to Fall

Recently we reviewed in these pages' election returns by generation showing that Vice President Kamala Harris won a majority of most generations but decisively lost Gen X, and thus the election as a whole. We Gen Xers shrugged off the daily looming prospect of global thermonuclear annihilation. Latchkey kids had more pressing things to concern themselves with. Worse still, we survived the cultural oppression of the Baby Boomers and their allegedly “classic” rock playing the same seven songs on infinite radio repeat. Punk, funk, new wave, alternative, grunge — please just give us something else to listen to!

But I digress; in addition to our shared childhood experiences, many in Gen X were the parents of school-aged children during the COVID-19 dumpster fire. This made many see red far more than even having to listen to Stairway to Heaven 18,589 times. K-12 traditionalists/reactionaries might hope to wait out the Gen X generation — some of us have become grandparents — we can’t live forever. Delightfully, still greater challenges for the status-quo tribe loom in the immediate future.

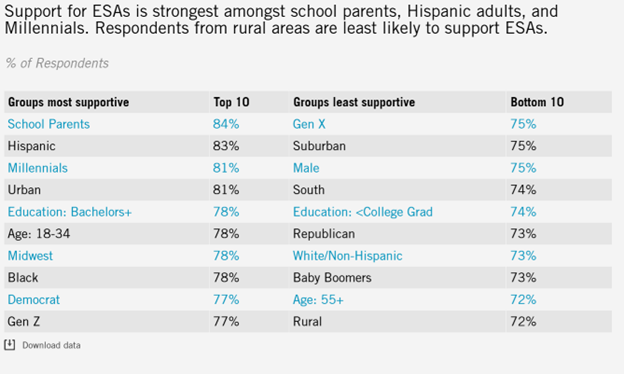

Polls, like the one above from Ed Choice, show that both Millennials and Gen Z show higher support for school choice than either Gen X or Baby Boomers. This is hardly surprising. There were only three channels on television (four if you count PBS) when Gen X was young, and we were thrilled when cable television came along and provided an additional 50 or so channels. Young people these days can stream anything, anytime, anywhere. Future generations will not even understand the phrase “cutting the cord” as they won’t have ever experienced a cord to begin with.

It's hard to imagine public education remaining one-size-fits-all in a world of ubiquitous customization. Democracy can be terribly unforgiving to candidates who attempt to give voters what they think they need rather than what they want. Ultimately this points to a bipartisan future for K-12 choice.

Chuck Todd for instance noted on election night:

Both Florida and Texas have been very aggressive about expanding school choice. Where have Republicans made the greatest gains among Hispanic voters? Florida and Texas. So, education, the economy, those issues, bread and butter issues, and that is how they talk to them. I’m not saying Democrats weren’t, but the cultural issues don’t play as well with Hispanic voters as they may with college-educated whites or even African Americans.

Political parties don’t generally volunteer to play the role of the nail indefinitely; it’s better to be a hammer. Gen Xers are old enough to have seen a bipartisan coalition for choice come, and to have seen it go. Will we see an effort to get a new bipartisan coalition rushing headlong as a new goal, or will we be waiting for the hammer to fall again?

Stay tuned.

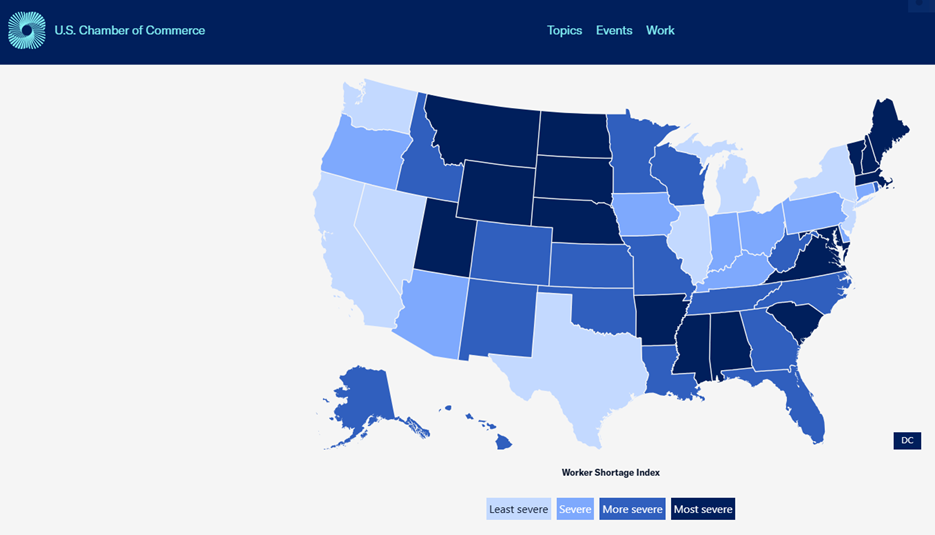

Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has calculated a worker shortage index for each state, calculating the ratio of people looking for work compared to the number of open positions. Florida, for example, has 53 people looking for work for every 100 open positions, making a worker shortage index of .53. The states with the most severe shortages stood at .36. Large structural changes are driving the shortage of workers, and they have implications for the future of the public education system.

Half of America’s 73 million strong Baby Boom generation reached the age of 65 in (editor’s note **gulp**) 2022. For the remainder of this decade, an average of 10,000 more baby boomers will reach the age of 65 daily until 2030, when all surviving boomers will be 65 or older. As the boomers exit stage left, a small Baby Bust generation began to enter the workforce as 16-year-olds in 2024. This generation had social media unleashed on them and then had their education disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Next, there is the demand for American labor to consider; it is up. A “re-shoring” of multiple industries began more than a decade ago due in large part to the shale-oil revolution producing the world’s lowest prices for natural gas. Citibank noted that natural gas now costs three to four times more in Europe than it does in the United States, thanks to the U.S. domestic shale gas boom.

The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced this trend. Companies are now seeking to insulate supply chains from political risk and cut time to market and respond to foreign wage inflation. Deloitte reported the results of a survey of 350 corporate presidents in 2022:

Transportation executives whose companies have begun preparing for nearshoring anticipate 20% of Asia-originating freight will move to closer-proximity markets by 2025…doubling to 40% of freight originations by 2030. Manufacturers’ expectations are similar, and 62% of them have begun this process already. Survey respondents expect agriculture, apparel, and consumer electronics to see supply lines being reconfigured the most.

So, summing up the story thus far, the demand for American labor is growing, but the supply is shrinking. Now recall the fall of 2021: Schools began to reopen; kids around the country went out to the school bus stop and…no one picked them up. Governors in multiple states called the National Guard to drive school buses. The causes for this occurred gradually and then suddenly.

The gradual part was an increased demand for drivers with a commercial driver’s license. Amazon and many other firms increased the demand for people with the same license required to drive a bus. School districts increasingly relied upon CDL holders who were not in the market for full-time work. The all of a sudden part of the story came when this universe of mostly older drivers did not feel eager to get on a bus with kids throwing their COVID masks at each other.

Districts were eventually able to find new drivers, and the National Guard tour of duties driving school buses ended. In the future, the CDL crisis of 2021 may be viewed as a suggestive bit of foreshadowing. The demand for American labor is increasing; the supply is decreasing, and the demand for public health care spending from those retiring Boomers will be in direct competition with education spending. Our Washington Olympians could try to fire up the money printing again to preserve as much status quo as possible, but we now have first-hand experience with the inflationary cost.

America’s public school system failed to meaningfully improve outcomes during multiple decades of steady increases in per-pupil spending above and beyond inflation. Is it possible they will do better during a period of heightened competition for public dollars and competition for labor?

Many human activities have become simultaneously less expensive and higher quality; it happens all the time. Public education, however, finds itself subject to a complex web of multi-jurisdictional red tape ensnaring a baseline district governance model highly vulnerable to regulatory capture. It’s not exactly the ideal circumstances for producing innovation or success.

Going forward, this politicized mess will have to increasingly compete with the elderly for public dollars and with a starved American labor market for workers. Not surprisingly a growing number of American families have decided to make alternate plans.

Somewhere around four years ago, public school systems around the country began “temporarily” shutting down as a reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. The United States had a plan, an allegedly best in the world plan, to deal with a pandemic. Well…

I recall the fiasco unfolding in my home state of Arizona. A panicked consensus in favor of school shutdowns grew based upon…other panicked moves to close schools in other states. Perhaps that is unfair. We also had the famed epidemiological sagacity of a group called “Arizona Educators United” to inform us.

This column read in part:

Arizona Educators United on Sunday issued a call for Ducey and Hoffman to close the schools for the rest of the year.

“Without immediate, large-scale, serious interventions, like closing schools for the remainder of the school year, the coronavirus outbreak is projected to overrun medical facilities by early to late May,” the group said.

Panic did not grip everyone in Arizona. I will never forget speaking to a friend of mine who worked in the Arizona Department of Education. I glumly noted that school closure seemed inevitable, and she told me “I would not do it.” When I asked her why, she responded:

How indeed?

Fifty-thousand or so Arizona students disappeared from school. Further evidence that students interpreted closures as having made schooling optional can be found in data showing that the rate of chronic absenteeism more than doubled for Arizona students. Academic achievement declined. It was even worse in many other states.

John Chubb and Terry Moe explained that the central problem with K-12 is politics, and the COVID-19 fiasco made that sad fact blindingly obvious. The task ahead lies in recovery and in fiasco-proofing your family as best you can for the future.

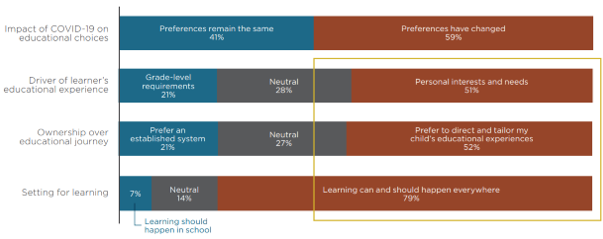

The Covid-19 pandemic proved that K-12 education was ripe for disruption. A new report from Tyton Partners finds that a majority of parents “prefer to direct and curate their child’s education rather than rely on local school systems.”

The Covid-19 pandemic proved that K-12 education was ripe for disruption. A new report from Tyton Partners finds that a majority of parents “prefer to direct and curate their child’s education rather than rely on local school systems.”

With many families educating their children at home during the crisis, parents discovered learning and personal growth can happen everywhere, not just in the classroom. Not only are parents choosing where, and how, their children are educated; they also are making choices on extracurricular activities like camp, tutoring, cultural enrichment and sports.

Could educational choice and extracurricular choice coexist, and how might it work?

Tyton Partners, with the Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust, set out to find answers to these questions with a new report, “Choose To Learn: Connecting In- And Out-Of-School Learning In A Post-Pandemic World.”

Researchers surveyed more than 3,000 parents and nearly 150 organizational leaders who offer in-school and out-of-school educational programs.

According to the survey, the pandemic fundamentally changed the way parents view K-12 education.

Parents’ values and beliefs toward K-12 learning

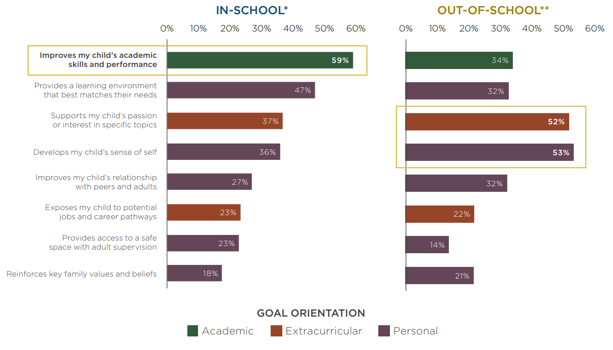

While parents still believe in-school learning is the greatest means of improving a child’s intellectual opportunity, Tyton Partners found that parents viewed out-of-school activities to be far better at supporting a child’s passions of interest and developing a child’s sense of self-worth.

Out-of-school activities were viewed as being better at helping students develop relationships with peers and adults and reinforcing key family values and beliefs. These out-of-school style activities may even be blended into non-traditional educational models, such as microschools or other alternative educational programs.

Top aspirations for child’s learning

Given the positive benefits of these out-of-school activities, researchers reviewed concerns over equitable access to extracurricular activities and alternative schools by minorities or low-income families. Alternative school options and extracurricular activities also remain unaffordable to most families, regardless of race or income.

Given the positive benefits of these out-of-school activities, researchers reviewed concerns over equitable access to extracurricular activities and alternative schools by minorities or low-income families. Alternative school options and extracurricular activities also remain unaffordable to most families, regardless of race or income.

Researchers provide two solutions to making alternative educational models and extracurricular activities more affordable: education savings accounts (ESAs) and public microgrants.

ESAs would provide funds directly to parents to pay for tuition, tutoring and other afterschool activities like camps, museum trips, sports and more. Microgrants include programs like VELA Education Fund offering grants to educational entrepreneurs, or Boston Public Schools’ “Opportunity Portfolio,” which provides grants to community organizations and enrichment programs to serve local students.

In addition to resolving equity issues, the researchers examined accessibility and quality issues as well.

Overall, the research launched to gain a better understanding of issues impacting every family, including the more than 40 million parents who send their children to public school, according to Christian Lehr, senior principal at Tyton Partners and lead author of the report.

“Relative to issues of equity and access, our local public districts play a crucial role for K-12 families,” Lehr said. “At the same time, families crave a wide variety of learning experiences. It is in this spirit that we examined parents’ aspirations at the intersection of in- and out-of-school learning, and ask: How can the K-12 sector deliver a stronger union of academic, extracurricular, and personal outcomes for all families, regardless of life or economic circumstances?”

Editor’s note: These survey results, with analysis from David M. Houston, Paul E. Peterson and Martin R. West, appear in the Summer 2022 issue of Education Next.

Editor’s note: These survey results, with analysis from David M. Houston, Paul E. Peterson and Martin R. West, appear in the Summer 2022 issue of Education Next.

The Covid-19 pandemic prompted the largest disruption to American education in living memory.

At the onset of the crisis in spring 2020, nearly every K–12 school, public and private, closed its doors. At the start of the next school year (see “Pandemic Parent Survey Finds Perverse Pattern,” features, Spring 2021), the decision to reopen for in-person instruction or to continue operating remotely varied widely among regions of the country, across school sectors—traditional district, charter, and private—and even from school to school in a given community.

By the end of the 2020–21 academic year, most K–12 students were back in their classrooms (see “Parent Poll Reveals Support for Covid Safety Measures,” features, Winter 2022), but the emergence of new variants of the virus and strict quarantine rules continued to disrupt the day-to-day business of teaching and learning well into the 2021–22 school year.

Many observers and pundits opined that the great disruption could usher in an era of sweeping changes to the American education system. Would families flee the public sector in droves? Would homeschooling emerge as a viable option for many more children? Or would the crisis prompt greater investments in public education, increasing spending and expanding the publicly funded K–12 infrastructure downward in age to pre-kindergarten and upward to community college?

The pandemic also revealed that the partisan differences that define much of contemporary American politics run even deeper than many imagined, as opinions on Covid-related public-health measures—school closures, vaccines, face masks, and more—became inextricably tied to one’s political identity.

Would the politics of education in the United States, with its long history of fractious but not necessarily partisan disagreements, be swept into the broader current of perpetual conflict between Democrats and Republicans? Did the last few years mark a great pivot point, signaling the emergence of two distinct, and distinctly partisan, views of how best to serve students?

The results of the 16th annual Education Next survey, conducted in May 2022 with a nationally representative sample of 1,784 American adults (see the methodology sidebar for more details), complicate many of these grand prognostications. While last year’s survey revealed sharp changes in support for a variety of education reforms (see “Hunger for Stability Quells Appetite for Change,” features, Winter 2022), public opinion on most issues has since rebounded to pre-pandemic levels.

There are, however, some important exceptions to this pattern. Americans’ perceptions of local school quality have declined since 2019, and support for homeschooling has risen over the course of the pandemic. Public enthusiasm for universal pre-K has increased dramatically, and support for higher teacher salaries is at its highest level in the survey’s history.

The Education Next survey also tells a more complex and nuanced story about the shifting relationship between political partisanship and public opinion on education issues.

To continue reading, click here.

Former U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has written a new book about the importance of education choice.

Editor’s note: Former U.S. Secretary of Education and longtime education choice champion Betsy DeVos is promoting her new book, “Hostages No More: The Fight for Education Freedom and the Future of the American Child,” which is set to be released on June 21. DeVos recently sat down with her former education department colleague, Denisha Allen. A former state scholarship student, Allen now serves as the director of public relations and content marketing at the American Federation for Children, a national organization that DeVos helped found and chaired before becoming education secretary in 2017. DeVos recalls how she first became interested in the idea of education choice as a young mother of a kindergartener. She also discusses how advocates have approached the issue over the years, how she worked promote education freedom while serving as education secretary, and how the pandemic pushed it to the forefront of parents’ concerns. She also talks about what she hopes readers will learn from the book. Here are some excerpts from the interview.

How DeVos became involved in the education choice movement: My oldest son, Rick, who is now 40 years old, was starting kindergarten. My husband, Dick, and I knew we were going to be able to send our children to whatever school we felt was best for them. So, we were shopping around visiting schools and discovered this amazing little Christian school serving the kids of the neighborhood around there. They had to raise 90 percent of their operating funds every year. Everyone who attended paid what they could. So, I started getting involved in that school, and the more I was there, the more I realized that there were multiple families who would have loved to have their kids in a school like that. So, I started, as we all did…we started trying to make the case to appeal to people through logic or through the lawyerly approaches or the legal side of the case as the reasons for granting education freedom and school choice and quickly realized it was going to take a lot of political muscle as well. And so, those things have developed over the last 30-plus years. But it was solely with a commitment to bringing policy into being in as many states as possible to allow families the kind of freedom they need to find the right fit for their children.

How the pandemic allowed education choice to take center stage: I think the last two years have really laid bare many of the challenges that many of us, if not all of us, have seen during the last number of years in a way people never anticipated. Whether it was lockdowns, mandates, curriculum issues, lack of rigor or a lack of actually learning anything, any number of issues have really brought the whole possibility of education freedom to a whole new level.

Why a book and why now? I didn’t set out to write a book and probably wouldn’t have if not for what unfolded the last couple of years. But again, I think it has really brought attention to the whole issue of education in a way that we couldn’t have anticipated. As you know, all of our focus while we were (in the Department of Education) has been on doing the right thing for students, and all activities were centered around highlighting different schools or different approaches that were bringing unique opportunities to students. The whole notion of rethinking education and the old institutional notion of one-size-fits-all approach, a lot of that work really helped lay the ground in many ways for the discussion we’re having today about bringing broader education freedom to those across the country. So, the book is my way to talk about how we fix education in America, and it brings into it the stories of lives that have been changed and kids who are on a totally different path because of these opportunities, and I hope it helps correct some of the mischaracterizations of my time in Washington and all of us who are involved in offering these types of opportunities through policy to kids in all states.

What is DeVos's main message to readers? I hope that (readers) will take away the notion that education freedom is something we have got to move toward for every student in this country. By education freedom, I should probably give my definition of what that means. I used to talk about school choice, and school choice was and still is a good description of what we’re talking about, but I don’t think it’s broad enough. When we think of school choice, we think of buildings, and I don’t think we have to think of only buildings. We need to think creatively about how kids can experience learning in their K-12 years in ways that we haven’t begun to dream of. And frankly, lots of people have been exploring that during the last two years with all of this COVID reality. So, you have families that have been banding together to in small homeschool consortiums have may become a micro-school. You have individuals who are customizing their education…education freedom, I think provides a new moniker or banner of what school, of what education, could be. I hope people will take away tools they can use to advance this in their own communities and their own state and on behalf of their own children, and I hope it will really encourage policy change to empower families to do just that.

Catholic schools in Florida, such as St. Joseph Catholic School in Tampa, contributed to an overall 6.3% enrollment increase in 2021-22, the biggest jump of any of the 10 states with the biggest Catholic school enrollments.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Tuesday in the Clarion Herald, the official newspaper of the Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans.

A panel of four Catholic education leaders touted the resiliency and flexibility of Catholic schools in the United States during and after COVID at the National Catholic Educational Association Convention (NCEA) April 21 in New Orleans.

“We have a great story to tell right now,” said Lincoln Snyder, president and CEO of the NCEA, mentioning how well Catholic schools performed during the pandemic and the increase in enrollment from 1.62 to 1.69 million students – the first gain in 24 years.

“Harnessing the power of that storytelling is going to be a great opportunity for us going forward,” Snyder said. “We are very different from other school systems.”

Moderating the panel, “The State of Catholic Education,” Jill Annable, senior vice president of programs for the NCEA, asked four pertinent questions about the state of Catholic education today.

New families came to Catholic schools because they wanted in-person learning, but stayed because they have fallen in love with the community and saw how well-served their children were by Catholic education, Snyder said. Federal scholarship programs also benefited families who maybe couldn’t afford tuition before.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This analysis from Daniel Hamlin, assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, and Paul E. Peterson, Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Government and director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard University, appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Education Next.

Editor’s note: This analysis from Daniel Hamlin, assistant professor at the University of Oklahoma, and Paul E. Peterson, Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Government and director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard University, appears in the Spring 2022 issue of Education Next.

As folk wisdom has it, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. And research shows that children are generally shaped more by life at home than by studies at school.

College enrollment, for instance, is better predicted by family-background characteristics than the amount of money a school district spends on a child’s education. Some parents have a specific vision for their child’s schooling that leads them to keep it entirely under their own direction. Even Horace Mann, the father of the American public school, who favored compulsory schooling for others, had his own children educated at home.

Homeschooling is generally understood to mean that a child’s education takes place exclusively at home—but homeschooling is a continuum, not an all-or-nothing choice. In a sense, everyone is “home-schooled,” and the ways that families combine learning at home with attending school are many.

Parents may decide to home-school one year but not the next. They may teach some subjects at home but send their child to school for others, or they may teach all subjects at home but enroll their child in a school’s sports or drama programs. Especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, the concept of homeschooling has become ambiguous, as parents mix home, school, and online instruction, adjusting often to the twists and turns of school closures and public health concerns.

Improving public understanding of the growing and changing nature of homeschooling was the purpose of a virtual conference hosted in spring 2021 by the Program on Education Policy and Governance at the Harvard Kennedy School. The conference examined issues in homeschooling through multiple lenses, including research, expert analysis, and the experiences of parents.

The event drew more than 2,000 registrants, many of them home-schooling parents. Their participation made clear that homeschoolers today constitute a diverse group of families with many different educational objectives, making it difficult to generalize about the practice.

The conference did not uncover convincing evidence that homeschooling is preferable to public or private schools in terms of children’s academic outcomes and social experiences, but neither did it find credible evidence that homeschooling is a worse option. Whether homeschooling does or does not deliver for families seems to depend on individual needs and the reasons that families adopt the practice.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education at The Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, appeared recently on dailysignal.com.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Jonathan Butcher, Will Skillman Fellow in Education at The Heritage Foundation and a reimaginED guest blogger, appeared recently on dailysignal.com.

Parents have spent the last two years dealing with lawmakers’ and school officials’ indecisions about school re-openings, a nightmare for many. Public officials have constantly alternated between remote and in-person learning, masking and unmasking, social distancing and not.

Now, many families are rejoicing as they see states lift their remaining COVID-19 restrictions. Getting their children caught up on two years’ worth of learning will be the only concern when they attempt to have a normal educational experience once again.

Or so one would assume.

A return to pre-COVID-19 conditions will not be enough to get American students on track when another major obstacle still plagues them: the youth mental health crisis.

There is no doubt the pandemic and many of the arbitrary policies made in response to it contributed to suffering. Children were not immune from mental grievances.

Locking youth populations down, increasing their screen time, and isolating them from their friends and teachers made them feel more stressed, clingy, fearful, helpless, and lonelier than ever before. As a result of these disruptions to their routine, every age group has seen a significant uptick in various mental health, speech, and developmental concerns.

To continue reading, click here.

Teachers at Seaside Community Charter School in Jacksonville, Florida, maintained a sense of humor – and a 6-foot distance – as they distributed supplies to families in a carline drive-by in March 2020 at the start of the COVID-19 shutdown.

Editor’s note: This article appeared Monday on reason.com. You can read more about how Seaside Charter School, pictured above, made a smooth transition to online learning here.

Experience demonstrates that there are a lot of reasons to support school choice, from escaping curricula wars to seeking academic excellence to adopting preferred teaching methods and schedules.

But the last couple of years also demonstrated that relatively small institutions dependent on attracting families that can enroll or disenroll at will are more nimble than traditional public schools in responding to crises.

Starting at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Stanford University's Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) examined how charter schools responded to the public health threat in comparison to traditional public schools. Looking at schools in California, New York, and Washington for the period from March to June 2020 and then for the 2020-21 school year, researchers found that charters were able to pivot from in-school teaching to remote instruction remarkably quickly.

"In multiple states and under varying conditions, the majority of charter schools we surveyed demonstrated resilience and creativity in responding to the physical and social challenges presented by COVID," CREDO announced Feb. 15. "They reacted strongly and acted quickly to shift to remote instruction. Communication was elevated as a priority. They assessed student and teacher needs for technology and mobilized resources and contacts to distribute technology and subsidize internet access."

Specifically, to keep kids learning, 83% of surveyed charter schools provided equipment, such as laptops, while 73% offered internet access.

To continue reading, click here.