The longer Florida's private school scholarship programs operated, the bigger the benefits for students in public schools.

That's the headline finding from a new study published this week in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

Researchers David Figlio, Cassandra Hart and Krzysztof Karbownik have been studying Florida's school choice programs for years. They sum up their latest findings this way: "We find that as public schools are more exposed to private school choice, their students experience increasing benefits as the program matures."

Earlier work by Figlio and Hart showed that competition with scholarship programs appeared to drive improvements in public schools, and studies have found similar effects in other states. But those studies looked at newly created or expanded programs.

This new paper looks at the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program over a much longer timeframe, from 2003 to 2018. The program grew sevenfold during that period, and eligibility for the scholarships expanded up the income ladder.

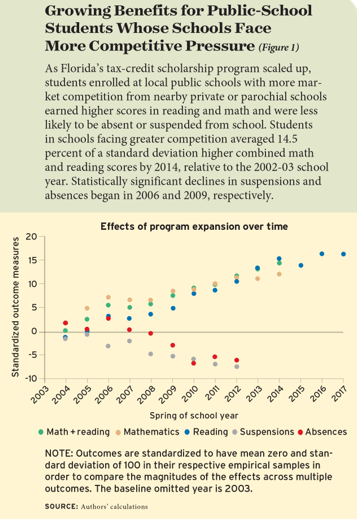

The paper compares student outcomes in highly competitive areas of the state, where students were especially likely to choose scholarships, with lower-competition areas. Public schools in the higher-competition areas saw larger decreases in student absences and suspensions, and larger increases in reading and math scores. These benefits strengthened over time. Some benefits that were not discernible when the program first launched, like the reduction in student absences, took years to develop.

Readers unfamiliar with the Florida landscape might assume this means that increased competition benefitted students in high-density urban districts and left their rural counterparts behind, but the areas with high densities of scholarship participation included the state's largest urban school district (Miami-Dade County) and its smallest rural district (Jefferson County).

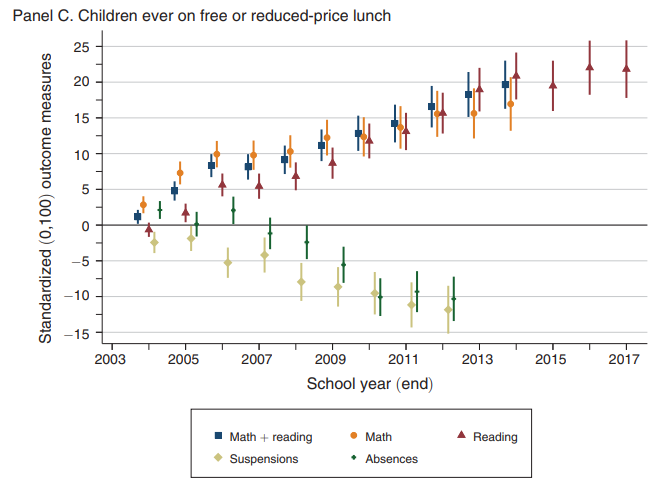

The benefits were uneven in a different way. They appeared stronger for lower-income students who qualified for free and reduced-price lunch (and thus were all eligible for means-tested scholarships).

Public-school students who qualified for free or reduced-price lunch saw improved reading and math scores, and reduced absences and suspensions, as Florida's tax credit scholarship program matured.

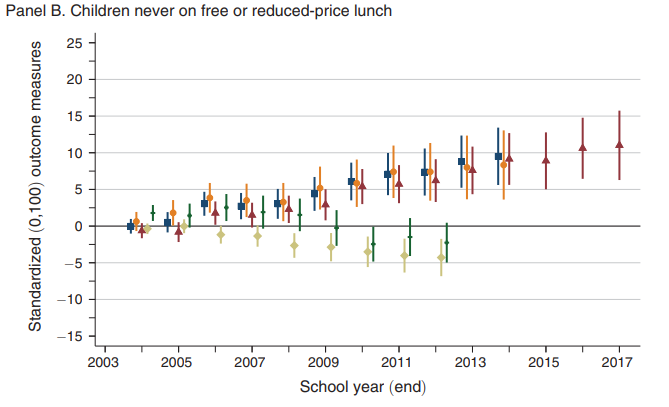

For other students with higher incomes, many of whom did not all qualify for scholarships, there were still benefits from competition, but they were smaller.

Students who did not qualify for free- and reduced-price lunch also saw benefits, but their improvements were smaller.

These results tee up some intriguing questions about the state's changing landscape, especially in the wake of HB 1, which this year made all students eligible for education choice scholarships and produced the largest expansion of scholarship participation any state has seen to date.

Will the benefits of competition be sustained, or even accelerated, with this new expansion? Will increased competition in more affluent areas accelerate public school improvement for higher-income students in public schools, who saw smaller benefits during the era of means-tested scholarships?

There is another set of questions left unanswered by quantitative studies. The numerical results don't say very much about what's going on inside schools that face increased competition. Do they improve because students find a better fit? Some data in the paper cast doubt on that explanation, because the composition of public-school students examined in the study does not appear to change very much. Do public school districts respond to intense competition by lowering class sizes or introducing new magnet programs? In some cases, yes, but the researchers also find reason to doubt that those shifts explain the improved results.

The bottom line is that, at least in Florida, growth of private school choice programs can benefit the vast majority of students who remain in the state's public schools, and those benefits appear to increase over time. Exactly how and why that happens remains a mystery worth exploring.

For two decades, the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program has created “a rising tide of competition” that “has lifted many boats.”

For two decades, the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program has created “a rising tide of competition” that “has lifted many boats.”

That’s according to researchers David Figlio, Cassandra Hart and Krzysztof Karbownik in a new report that appeared recently in Education Next, an online education magazine published by Harvard University’s Program on Education Policy and Governance.

The scholarship program, which became law in 2001 and first offered scholarships in 2002, expanded from an initial 15,000 students to more than 100,000 last year. Over the program’s 20-year history, more than 1 million scholarships have been awarded to low- and middle-income students.

The scholarship program, which became law in 2001 and first offered scholarships in 2002, expanded from an initial 15,000 students to more than 100,000 last year. Over the program’s 20-year history, more than 1 million scholarships have been awarded to low- and middle-income students.

According to the researchers, the scholarship program has not only positively impacted the private school students who have received them; it also has impacted public schools.

The data show that public schools facing competitive pressure from nearby private schools saw the biggest improvement in student outcomes, including increased math and reading scores and fewer suspensions and student absences. Lower-income students saw the most improvement.

“As the program scaled up,” wrote the researchers, “academic and behavioral outcomes improved for students attending traditional public schools.”

Schools facing less competitive pressure averaged 68% white students, with 67%of students eligible for the federal free or reduced-price lunch program. Schools facing more competitive pressure were 63% non-white, with 76% of students eligible for the lunch program.

Schools facing more competitive pressure started with poorer student achievement but made larger gains, suggesting the scholarship program has helped reduce achievement gaps between majority and minority students.

Students at all three locations of Academy Prep -- Tampa, St. Petersburg and Lakeland -- routinely matriculate to top high schools and go on to attend top colleges. All Academy Prep students attend on state scholarships.

There is no evidence that students who use Florida school choice scholarships return to public schools worse off academically.

There is no evidence that students who use Florida school choice scholarships return to public schools worse off academically.

But that doesn’t stop critics of education choice from repeating variations on that claim.

The Florida League of Women Voters is the latest to air this “damaged goods” myth. In a Feb. 21 newspaper op-ed criticizing Senate Bill 48, which would convert Florida’s school choice scholarships into education savings accounts, two of its officials wrote:

“Stories abound of children who return to their neighborhood public school after a private school closes, only to find they are far behind academically.”

But for the qualifier “after a private school closes,” the Florida League of Women Voters op-ed echoes a charge that choice opponents have been levelling for years (for example, here and here.)

We can’t say with certainty whether “stories abound.” But data to support such claims certainly does not.

The authoritative take on this issue comes from respected education researcher David Figlio, dean of the School of Education and Social Policy at Northwestern. For years, Figlio was tasked by the state of Florida with annually analyzing the standardized test scores of students using the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, the biggest choice scholarship program in the nation. (The scholarship is administered by nonprofits such as Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

In his 2011-12 report, Figlio addressed the academic performance of scholarship students who return to public schools. He wrote:

FTC participants who return to the public sector performed, after their first year back in the public schools, in the same ballpark but perhaps slightly better on the FCAT than they had before they left the Florida public schools. The most careful reading of this evidence indicates that participation in the FTC program appears to have neither advantaged nor disadvantaged the program participants who ultimately return to the public sector.

Figlio also wrote:

These pieces of evidence strongly point to an explanation that the poor apparent FCAT performance of FTC program returnees is actually a result of the fact that the returning students are generally particularly struggling students.

Subsequent analyses led to the same conclusion.

The best available evidence doesn’t point to shortcomings with choice scholarships. If anything, it underscores the need for even more options for the most fragile students.

Other evidence also turns the League of Women Voters claim on its head.

Thirteen years’ worth of test score analyses offer remarkably consistent findings about Florida Tax Credit Scholarship students. No. 1, they were typically the lowest-performing students in their prior public schools. And No. 2, they’re now, as a whole, making a year’s worth of progress in a year’s worth of time.

A 2019 Urban Institute study found even more encouraging results: The same students are up to 43 percent more likely than their public school peers to enroll in four-year colleges, and up to 20 percent more likely to earn bachelor’s degrees.

These outcomes don’t suggest damaged goods.

They suggest more students living up to their potential.

As Florida senators get their first look today at a new private school scholarship for economically disadvantaged students, some familiar taunts about academic results for the existing Tax Credit Scholarship have resurfaced. Be wary of rhetorical flourish.

Yes, the low-income scholarship students are not required to take the Florida Standard Assessment administered in traditional public schools. But they are required to take state-approved nationally norm-referenced tests whose academic validity is not in dispute.

So those who claim “Floridians have no idea if private schools are succeeding,” as one South Florida newspaper wrote recently, are ignoring 10 years of testing data to the contrary. They also neglect extraordinary new independent research that shows scholarship students are more likely to attend and graduate from college.

The testing trend line

Students in grades 3-10 on the Florida Tax Credit Scholarships have been required since 2006 to take a standardized test, and most take the Stanford Achievement. In the most recent report, their average percentile ranking in reading was 48 and in math was 46. That’s basically average, which is made more encouraging by the fact that these students are among the poorest in the state (and were the lowest performing from public schools they left).

The more important measure is whether the students are learning, and the bottom line has been almost identical each year: These low-income students have achieved the same annual gains as students of all income levels nationally.

Test score gains for individual schools with at least 30 tested scholarship students are also reported annually. In the most recent report, 342 schools were listed.

Comparisons with public school students

When budget cuts removed norm-referenced portions of the state test in 2011, researchers were no longer able to make a direct comparison between scholarship and public school students. In that 2011 academic findings report, though, researcher David Figlio concluded that scholarship students outperformed their peers in public schools, even though the public school students had higher incomes.

Figlio wrote of what he viewed as increasing gains: “These differences, while not large in magnitude, are larger and more statistically significant than in the past year's results, suggesting that successive cohorts of participating students may be gaining ground over time.”

Students who enter and leave the scholarship

From the earliest years, state researchers have found that scholarship students who come from public schools were among the lowest academic performers in schools that themselves had disproportionately low test scores. That’s no slight on the public school. It’s intuitive. If a student is doing well in his or her current school, why change?

Similarly, scholarship students who return to public school are among the lowest performers in the private school they leave behind.

This recurring fact has been stretched in the current debate to imply that scholarship students who return to public schools have learned essentially nothing. That’s not what test results show, and, further, Figlio addressed that question head-on in his 2013 report. He looked at students who had switched twice – from public to private and back to public. In those cases, the state public test scores remained essentially the same.

Wrote Figlio: “FTC participants who return to the public sector performed, after their first year back in the public schools, in the same ballpark but perhaps slightly better on the FCAT than they had before they left the Florida public schools. The most careful reading of this evidence indicates that participation in the FTC program appears to have neither advantaged nor disadvantaged the program participants who ultimately return to the public sector.”

Beyond test scores

In February, the respected Urban Institute released perhaps the most significant research in the scholarship program’s history. The report was a followup to work released in 2017 and was directed again by the Institute’s Director of Education Policy, Matthew Chingos, who has a PhD in government from Harvard University. His team matched data between roughly 89,000 scholarship and public school students from 2003 to 2011, representing the largest study of its kind in the nation.

The institute found that scholarship students are more likely than their public school peers to attend and graduate from college. The difference is striking.

Scholarship students as a whole were up to 43 percent more likely to attend college, a difference that rose to 99 percent for those on the scholarship at least four years. Similarly, scholarship students as a whole were up to 20 percent more likely to get a degree, a difference that rose to 45 percent for those on the scholarship for at least four years.

Tenure and achievement: When Florida legislators eliminated teacher tenure in 2011, they argued that making it easier to get rid of bad teachers could lead to better student academic results. Seven years later, a study finds that achievement by students in vulnerable schools has improved only slightly, and that there's no conclusive way to tell if the elimination of tenure played a role in that modest success. "The intent (of the statute) was to raise student achievement by improving the quality of instructional, administrative and supervisory services in the public schools," write researchers Celeste Carruthers, David Figlio and Tim Sass. "Whether (the law) or policies like it succeed in attracting and retaining high quality teachers remains an open question." Brookings Institution. Gradebook.

Tenure and achievement: When Florida legislators eliminated teacher tenure in 2011, they argued that making it easier to get rid of bad teachers could lead to better student academic results. Seven years later, a study finds that achievement by students in vulnerable schools has improved only slightly, and that there's no conclusive way to tell if the elimination of tenure played a role in that modest success. "The intent (of the statute) was to raise student achievement by improving the quality of instructional, administrative and supervisory services in the public schools," write researchers Celeste Carruthers, David Figlio and Tim Sass. "Whether (the law) or policies like it succeed in attracting and retaining high quality teachers remains an open question." Brookings Institution. Gradebook.

Special session request: Democrats in the Legislature resort to an obscure rule to force a poll of all lawmakers on the idea of calling a special session to deal with educational funding. Ordinarily, Senate and House leaders decide if a special session is needed. But when they resisted, 35 Democratic members filed petitions with the secretary of state to conduct the poll; 32 are required to force the polling. They don't expect to be successful, but say it will put legislators on the record in an election year. Answers to the poll are due May 24. Gradebook.

Students in Ohio's private school voucher program make less academic progress than their peers in public schools. But the program has a positive effect on public school performance, perhaps because it spurs competition. While the program is aimed at mostly disadvantaged students from struggling public schools, it tends to attract the better-off students within that group.

In short, the key findings from a new, deep dive into the Buckeye State's EdChoice program undercut some of the usual talking points on both sides of the school choice debate.

The report, published last week by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, is the first study of Ohio's largest voucher program based on individual test results. The study looked at data through the 2012-13 school year for a program that serves some 18,000 students.

The research was done by David Figlio, a researcher who's well known in Florida school choice circles and previously performed evaluations of Florida's tax credit scholarship program*, along with Krzysztof Karbownik, a postdoctoral research fellow at Northwestern University.

Their findings have implications not just for Ohio, but for private school choice programs in other parts of the country. Here's a look at what the study found, and why it matters.

The results

Student disadvantages

Ohio's voucher program is targeted at students who attend public schools that score low in the state accountability system. Students who use vouchers tend to be economically disadvantaged, but compared to students who qualify for vouchers, the ones who actually use the program tend to be better off, both academically and socioeconomically. (more…)

Anna Egalite

Critics of school choice programs often say they harm public schools, and that taxpayer resources would best be used educating "all children" in public schools.

A new study, however, joins a growing body of research suggesting competition from private school choice programs may actually lead to small, but detectable, improvements in public school student achievement.

The study, “Competitive Impacts of Means-Tested Vouchers on Public School Performance,” by Anna Egalite a post-doctoral fellow at Harvard University, examines the impacts of vouchers on public school students in Indiana and Louisiana.

She finds the voucher programs had a small but positive impact on public-school students' English achievement in both states, and small but positive impacts on Math in Louisiana, which she attributes to the competitive effects of students having new private school choices available.

To study the impact, Egalite employs four measurements: The distance between public and private schools, the density of private options near public schools, the diversity of private schools nearby and the concentration of private school options (one operator or many). She then focuses on the achievement of students who remain in public schools after low-income classmates accept vouchers to attend private schools.

Egalite summarized her research in a recent article for the Friedman Foundation, stating, “the positive impacts are generally small but appear to be largest in the lower-performing public schools, using measures of competition that include concentration and diversity of private school competitors.”

The low-income students who participate in the country's largest K-12 private school choice program are keeping pace with students of all income levels nationally, according to the latest independent evaluation.

The latest annual report, released Tuesday, tracks learning gains for participants in the Florida tax credit scholarship program in the 2012-13 school year.

Overall, the results are similar to previous years. The report shows students who participate in the program are among the state's most disadvantaged, and that on average, they meet one of the most basic expectations for student learning: A year's worth of growth after a year's worth of instruction.

Each year, schools that serve students on the scholarship program report their test scores to an independent research team led by David Figlio of Northwestern University, who analyzes their performance on national norm-referenced tests and compares the results to students nationwide.

This is the seventh such report, and the bottom line is familiar. As Figlio writes, tax credit scholarship "participants on average keep pace with national norms, suggesting that they neither gain ground nor lose ground on average relative to a national peer group that includes not just low-income families but also higher-income families."

The report also finds:

Data on student learning gains have more or less held constant from one year to the next, though the report notes wide variation among students in the program. More than one in 10 students fell behind by more than 20 percentile points in reading, while exactly one in 10 made outsize gains of the same amount. The numbers for math were similar.

There was also major variation between schools. (more…)

Students with access to a wider range of public school choices may be less likely to sign up for private school vouchers.

That's one of the most significant new findings of a Florida-based study that provides a detailed picture of factors that drive parents to "shop around" for the best education options for their children.

"The results so far suggest that the contexts of students’ own public schools, their private school options and their public school options are all related to participation in the voucher program," writes Cassandra Hart, an assistant professor at the University of California-Davis who authored the study.

Hart previously worked with David Figlio of Northwestern University on other school choice-related research, including an earlier analysis of students who participate in Florida's tax credit scholarship program for low-income students. Figlio’s annual evaluations of the program (which is administered by organizations like Step Up For Students, which co-hosts this blog) have found that students who participate are more disadvantaged than eligible students who don't, and that participants come disproportionately from struggling schools.

Hart's new paper, published in the June edition of the journal Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, examines similar data. But it also expands on earlier research by analyzing a wider range of information, including teacher and principal surveys about school climates, and by analyzing the "markets" for public and private school enrollment.

Hart compares the school and individual characteristics of 555,271 students who may have been eligible for scholarships with 2,764 new scholarship participants from the 2007-08 school year, to look at factors that may have spurred the latter to participate.

In what she writes may be the study's most "novel contribution," Hart finds that students with a robust set of public school options – with a large number of charter schools in a 5-mile radius, or in school districts with popular open enrollment programs – appear less likely to sign up for tax credit scholarships than those with fewer such options. (more…)

The latest report on academic performance in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program devotes historic attention to evaluating the students who enter and, later, leave. This is the first time this subset has been thoughtfully and empirically analyzed to determine who these students are, why they leave and how they perform once they return to public schools. The researcher's findings lend credible support to common sense: students who struggle seek other options.

The latest report on academic performance in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program devotes historic attention to evaluating the students who enter and, later, leave. This is the first time this subset has been thoughtfully and empirically analyzed to determine who these students are, why they leave and how they perform once they return to public schools. The researcher's findings lend credible support to common sense: students who struggle seek other options.

The reasons that students transfer schools and how they perform can be overstated by supporters and opponents of the scholarship program alike. It is important to clarify the contradictory claims in this debate as more than 60,000 students enter the scholarship program this fall. The report, written under contract with the state by respected Northwestern University researcher David Figlio, faults neither the public schools nor the private schools, and simply asserts that students seek new schools because their prior option didn’t work for them.

For example, Figlio reports that for six consecutive years the students entering the scholarship program “tend to be the lowest performing students in their prior (public) school” and this is a “trend that is growing stronger over time.” This is not to say the public schools as an institution are failing low-income students, but more likely that the particular public school didn’t meet the unique learning needs of the child who chose the scholarship. Parents are seeing their child struggle and they are using scholarships to pursue new options.

The same could also be true for students who return to public schools. (more…)