Editor’s note: This month, redefinED is revisiting the best examples of our Voucher Left series, which focuses on the center-left roots of school choice. Today’s post from December 2015 describes efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot.

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

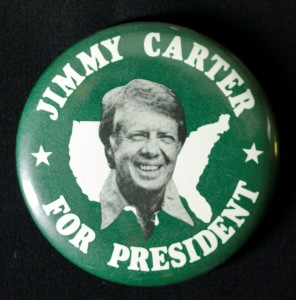

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

Catherine Robinson (second from left): "The next time my colleagues on the left yell and scream about Republicans turning on their values to support President Trump, I would like them to look in the mirror. You, too, are turning on your values to support a union and a system that limits opportunities for the people you claim to care about the most."

I’ve been a militant advocate, organizer and member of the Democratic Party for 30 years. A few months ago, I quit identifying as a Democrat.

It had been building within me for a while. I could no longer stomach the Democratic Party’s support for an education system that hurts so many poor and working-class families.

Democratic Party politicians have repeated their lies about educational options so long, they’ve begun to believe those lies. And they do this while so many of them can afford to move into desirable neighborhoods with good schools, or send their children to private schools.

I wonder how they sleep at night.

As far back as I can remember, I’d been raised to firmly identify and side with the poor and working class. My relatives were teamsters, union members and union organizers, Irish immigrants who fought for everything they got.

In college, I officially began my activism career by joining Students Against Apartheid. That led to gigs with Amnesty International, Greenpeace, Jerry Brown for President, Tampa AIDS Network, Florida Public Interest Research Group, and Sierra Club.

I worked as a counselor where I helped women choosing to end their pregnancies, sometimes holding their hands as they endured the most difficult moment of their lives. I marched on Washington and appeared on local talk shows, insisting that women had a right to control their reproductive lives.

I was almost arrested three times: protesting nuclear power, demanding an end to the war in Kuwait and demonstrating against animal cruelty.

For my 21st birthday, more than anything, I wanted an FBI file.

After college, I taught at alternative high schools and helped mostly young men, who had been expelled or arrested, turn their lives around. I also taught in district schools for students with special needs. All the while, I organized and advocated to repeal the Second Amendment, ensure marriage equality for all, protest armed conflict, provide for universal health care, expand voting rights, oppose private prisons and put out of business all circuses, rodeos and Sea World.

Six years ago, I met Michelle Rhee. I took a job with her national non-profit, organizing parents in several states to lobby for laws that put children’s needs ahead of adults’. Much to my surprise, Democratic friends and colleagues didn’t support this career move. (more…)

About 10,000 people, most of them black and Hispanic, rallied in Tallahassee in 2016 against the lawsuit that sought to kill the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship. Do Democrats running for governor understand who they are really criticizing when they reject school choice?

If you asked parents of students victimized by bullying (like this one, this one and this one) to describe the school choice scholarships that helped their kids find some educational peace, they’d probably offer words like “life-saving” and “miraculous.”

To Gwen Graham, though, the word that comes to mind is “diabolical.”

“Diabolical” is how Graham, a Democratic candidate for governor in Florida, described Florida’s new Hope Scholarship, which lawmakers engineered to give options to all bullying victims. “It is another move by the Legislature to decrease the funding in Tallahassee and increase the funding for their private and charter schools,” she told the Tallahassee Democrat editorial board. “It is diabolical. It truly is.”

That Democratic candidates might feel obliged to condemn school choice is no surprise, given the fact that teachers unions, whose members work almost exclusively in district-operated schools, contribute heavily to the Democratic Party. That’s even true in Florida, arguably the most choice-friendly state in America. But unlike many other states, where school choice is still an abstraction, candidates who denounce choice in Florida are also explicitly denouncing the hundreds of thousands of parents who choose. Here, growing numbers of parents in core Democratic constituencies freely choose charter schools and private school scholarships, and surveys show they like what they have found.

I’m no political analyst. But the basic math would seem to be a caution flag for Democrats. Since the last gubernatorial election in 2014, the number of students using the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, the largest private school choice program in America, has climbed more than 50 percent, to 107,000. The number of charter students has increased by about 20 percent, to nearly 300,000.

Judging by the demographics, their parents lean heavily Democratic. The average family income of a tax credit scholarship student is $25,360 a year, and 68 percent of the students are black or Hispanic. In Florida charter schools, 62 percent of students are black or Hispanic.

Florida has also created a major new choice program since the last election – the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs such as autism and Down syndrome. It now serves more than 10,000 students. I couldn’t hazard a guess about their parents’ politics, but I know they’re signing up so quickly the scholarship now has a waiting list, and they are the kind of parents who aren’t likely to be amused by politicians who want to take away education tools that are helping their children.

Remember, too, that Florida’s past two gubernatorial elections were squeakers. (more…)

This is the latest post in our series on the center-left roots of school choice.

Jimmy Carter once touted school vouchers, telling readers of Today's Catholic Teacher in 1976: "While I was Governor of Georgia, voters authorized annual grants for students attending private colleges in Georgia. We must develop similar, innovative programs elsewhere for non-public elementary and secondary schools if we are to maintain a healthy diversity of educational opportunity for all our children." (Image from Wikimedia Commons)

The confirmation fight over new U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has at least temporarily pulled Congressional Democrats from the growing bipartisan consensus on school choice. But this political showdown, and the extent to which it was animated by the teacher unions, is not new.

We can probably trace its beginnings to Jimmy Carter. It was during Carter’s presidency that intraparty politics began to pry the Democratic Party from its embrace of school choice. A couple of letters from Carter to Catholic educators, four years apart, captures the shift.

In September 1976, then-candidate Carter wrote to Today’s Catholic Teacher. (Go to page 11 here.) He praised Catholic schools; referred to the “right” of low- and middle-income Americans “to choose a religious education for their children;” and argued for school choice in terms of opportunity and diversity, as pro-choice progressives had long done. He said he was committed to finding “constitutionally acceptable” ways to provide financial assistance to parents whose children attend private schools. And, as a kicker, he gave a thumbs up to vouchers:

In September 1976, then-candidate Carter wrote to Today’s Catholic Teacher. (Go to page 11 here.) He praised Catholic schools; referred to the “right” of low- and middle-income Americans “to choose a religious education for their children;” and argued for school choice in terms of opportunity and diversity, as pro-choice progressives had long done. He said he was committed to finding “constitutionally acceptable” ways to provide financial assistance to parents whose children attend private schools. And, as a kicker, he gave a thumbs up to vouchers:

“While I was Governor of Georgia, voters authorized annual grants for students attending private colleges in Georgia. We must develop similar, innovative programs elsewhere for non-public elementary and secondary schools if we are to maintain a healthy diversity of educational opportunity for all our children.”

Carter’s pro-choice, pro-voucher position is fascinating for all kinds of reasons. Today’s left has no clue about its own past support for school choice. And as the Carter letter shows, choice wasn’t some fringe phenomenon on that end of the spectrum.

It’s also fascinating because Carter changed his tune at the end of his term, a turnabout that generally marked the beginning of the left’s resistance to choice (at least the white left) and a shrinking of that common ground we’re seeing again, post-Trump. As Doug Tuthill has written, that late ‘70s flip-flop has everything to do with the rise of the teachers union as a force within the Democratic Party, and little to do with progressive values.

The key point on the timeline is 1976, when the National Education Association (NEA) endorsed a presidential candidate for the first time. That would be Carter.

Four years later, his administration scrambled to write a follow-up to Today’s Catholic Teacher. Republican nominee Ronald Reagan had written a first-person letter to the magazine, and the magazine let Carter’s people know their initial response – a statement from the administration – paled in comparison. “HURRY HURRY HURRY,” one of Carter’s media liaisons urged the PR team in a memo: “This message conceivably could be in every Catholic publication in every Catholic school.”

The team shifted into high gear. But the resulting letter surely didn’t fire up undecided Catholics.

It gave Catholic schools credit for playing a “significant role” in educating “millions of low and middle income Americans.” But instead of a continuing commitment to find constitutionally acceptable ways to provide aid to private school parents – which Carter promised in 1976 – the president would only commit to supporting constitutionally appropriate steps to get Catholic schools “their equitable share of funds provided under our federal education programs.” Clearly, a far lesser goal.

Documents in the Carter Presidential Library show what was scrubbed during editing. David Rubenstein, then one of Carter’s domestic policy advisers, nixed language that said Carter reported the administration’s efforts to help private schools to the Democratic Party platform committee. He also scratched out Carter’s support for platform language that backed tax aid for private school education. “Definitely NO,” he wrote next to the strike-through. “I don’t see any advantage to getting into the Platform,” he commented in another memo.

Also removed was a description of parochial schools that said “in many areas, they provide the best education available.” And wording that said without such schools, millions of Americans “would have been denied the opportunity for a solid education.”

Caught between the Reagan Revolution and teachers unions, Democratic support for school choice faded for a decade. It began to pulse again in the 1990s, with the advent of charter schools. Then it slowly branched into other choice realms, nudged by advocacy groups that worked tirelessly to build bipartisan and nonpartisan bridges, and welcomed by Democratic constituencies who liked having options.

That middle ground has been steadily growing, and Florida is a prime example. A few months ago, the Sunshine State elected two pro-school choice Democrats to Congress. A year ago, the state Legislature expanded America’s biggest education savings account program with universal bipartisan support. For the past two and a half years, a remarkably diverse coalition battled legal efforts to kill the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship, which now serves nearly 100,000 kids. Three weeks ago, it won.

Masses of energized parents, most of them black and Hispanic, helped fuel that legal victory. That force wasn’t in place when Jimmy Carter followed the path of least resistance. But it’s here now, and Democrats can only ignore it for so long.

This is the all-in-one version of our recent serial about efforts to put school vouchers on the 1980 California ballot. It's part of our ongoing series on the center-left roots of choice.

The woman stopped the professor as they were leaving church near campus.

It was the fall of 1978 in northern California, and Jack Coons was a local celebrity. Or at least as much a celebrity as you can be if you’re a legal scholar who specializes in education finance.

He and Stephen Sugarman, a fellow law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, had been central figures in a series of court decisions in the 1970s that would dictate a more equitable approach to how California funds its public schools.

They had also just written a provocative book.

It called for scrapping the existing system of public education, and replacing it with one that gave parents the power to choose schools – even private schools. This stuff about “vouchers” was out there, but intriguing enough to generate some buzz. Newsweek gave it a plug.

My cousin is Congressman Leo Ryan, the woman told Coons. He’s interested in education.

Why don’t you and your wife join us for dinner?

***

It sounds crazy, but that chance encounter could have changed the face of public education in America. For one wild year in late ‘70s California, liberal activists set the stage for the most dramatic expansion of school choice in U.S. history.

Today’s education partisans have no clue it almost happened. But it almost did. And if not for some remarkable twists of fate, it might have.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, school choice was capturing the imagination of progressives who thought poor kids were being savaged by elitist public schools. Liberal intellectuals in places like Harvard and Berkeley were happy to tinker with the notion of school vouchers encapsulated by conservative economist Milton Friedman in 1955. They tried to cultivate varieties that included controls they believed necessary to ensure fairness for low-income families.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen D. Sugarman were among them. And in 1978, they unexpectedly got an opening to put their vision of school choice on the ballot in the biggest state in America.

It started with the dinner invitation.

***

Cue “Staying Alive.”

Disco was king. Jimmy Carter was president. And across the bay from Berkeley, the punk band Dead Kennedys was blasting its first angry chords. But in 1978, Coons and Sugarman still hadn’t gotten the carbon-copy memo that the ‘60s were over.

The ballot initiative they detailed in their 1978 book, “Education by Choice,” wasn’t gradual change, organic growth, nibbling at the edges.

It was revolution. (more…)

This is the latest in our series on the center-left roots of school choice, and Part II of a serial about a voucher ballot initiative in late ‘70s California. In Part I, law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman find a surprise supporter in U.S. Rep. Leo Ryan.

The Berkeley professors had found a powerful ally.

Congressman Leo Ryan was popular and fearless, a liberal with a maverick streak, a square peg with a common touch. It’s a safe bet he was the only member of Congress with a master’s in Elizabethan literature. And importantly for a ballot initiative that sought to make school choice the law of the land, he had been a teacher in California public schools.

Ryan also had a knack for making headlines.

Before election to Congress in 1972, he served nine years in the state assembly, where he became famous for exploring the nitty gritty behind the news. One newspaper called it “investigative politics.”

After riots in Los Angeles, Ryan worked as a substitute teacher in the Watts neighborhood. A few years later, he went undercover to experience death row at Folsom Prison. As a congressman, he visited Newfoundland to investigate the slaughter of baby seals, at one point laying down on the ice between a hunter and a seal pup.

As fate would have it, Ryan was also a voucher guy.

Years later, Jackie Speier, his former aide, would point to his support for school choice as a prime example of his political independence. Ryan “seemed unlike other politicians,” Speier said. “He was provocative; he didn’t mince words or beat round the bush; he told you what was on his mind whether you wanted to hear it or not; and he took pride in not being able to be pigeonholed into any one ideology.”

Ryan may have been willing to buck his party on vouchers. But it’s also true it wasn’t as odd for Democrats in the 1970s to back public support for private schools.

In 1977, Democratic U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan introduced a bill for tuition tax credits that drew 50 co-sponsors – 26 of them Republicans and 24 of them Democrats. At that time, the previous three Democratic candidates for president, Hubert Humphrey, Eugene McGovern and Jimmy Carter, had backed similar proposals on the campaign trail.

According to Coons, Ryan was all in on the voucher initiative.

After their last meeting, he said Ryan told him: “You guys are going to polish this up as best you can, and we’ll get ready to announce it and start pushing it through the process just as soon as I get back.”

The congressman was headed to South America.

***

As word spread, panic mushroomed.

The Los Angeles Times predicted the voucher initiative would be “the biggest and most bitter fight over schools in many years.” State Superintendent Wilson Riles predicted “chaos.” The executive secretary of the powerful California Teachers Association, Ralph Flynn, said his group would defeat the proposal “whatever the cost.”

Even Al Shanker, the legendary leader of the American Federation of Teachers, weighed in, saying the California proposal could produce “the fight of the century.”

By early 1979, Riles was urgently contacting supporters, mobilizing for a statewide campaign.

If this thing gets on the ballot, he told the San Jose Mercury News, “who knows what might happen.”

Game on.

***

Coons and Sugarman didn’t dream up their plan on a whim. They had been refining it for a decade.

The motivation was simple – to give parents, particularly poor parents, real power to determine the best education for their children. But the details were complex. Unless the new system was well designed and regulated, they believed, low-income children would continue to be denied a fair shake.

The professors envisioned three types of K-12 schools under a new banner of public education, all to be called “common schools.” There’d be: (more…)

On Sept. 17, 1976, the NEA endorsed Jimmy Carter for president – the first presidential endorsement in the organization’s history. With this endorsement, it joined with the other major teachers union, the American Federation of Teachers, to become a dominant force in the Democratic Party. Image from the Schell Collection.

This is the latest post in our series of the center-left roots of school choice.

Much of the opposition to private school choice seems to emanate from the Democratic Party, but this wasn’t always the case. Just look at the party platforms.

From the 1964 to 1984, the Democrat Party formally supported the public funding of students in private schools.

The 1964 platform stated, “New methods of financial aid must be explored, including the channeling of federally collected revenues to all levels of education, and, to the extent permitted by the Constitution, to all schools.” The 1972 platform supported allocating “financial aid by a Constitutional formula to children in non-public schools.” The 1976 platform endorsed “parental freedom in choosing the best education for their children,” and “the equitable participation in federal programs of all low- and moderate-income pupils attending all the nation's schools.”

Thanks to the influence of U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a New York Democrat and devout Catholic, the party’s 1980 platform stated “private schools, particularly parochial schools,” are an important part of our country’s educational system. It committed the party to supporting “a constitutionally acceptable method of providing tax aid for the education of all pupils.” In 1984, the platform again endorsed public funding for “private schools, particularly parochial schools.”

Then the shift began. The 1988 platform was silent on the issue, and by 1992 the Democrats had formally reversed position, stating, “We oppose the Bush Administration's efforts to bankrupt the public school system — the bedrock of democracy — through private school vouchers.”

The party’s current position on school choice was formalized in 1996. That year’s platform endorsed the expansion of public school choice, including charter schools. But it also reiterated “we should not take American tax dollars from public schools and give them to private schools.”

The Democratic Party’s shift from supporting to opposing public funding for low-income and working-class students in private schools can be traced back to an event that also helped spur the growth of modern teachers unions: The 1968 teachers strike in New York City.

This strike pitted the low-income black community of Ocean Hill-Brownsville in Brooklyn against the primarily white New York City teachers union. The issue was whether local public schools would be controlled by the Ocean Hill-Brownsville community or by a city-wide bureaucracy. The union vehemently opposed decentralization since its business model was built around a one-size-fits-all collective bargaining agreement with centralized management.

The strike lasted from May to November 1968. Given school districts are usually the largest employer in most communities, union power quickly grew. (more…)

This is the second post in our series on the Voucher Left.

Way back in 1978, when Bee Gees ruled the radio and kids dumped pinball for Space Invaders, a couple of liberal Berkeley law professors were promoting a variation on “universal” school vouchers that they believed would ensure equity for the poor. Along the way, they foreshadowed a revolutionary twist on parental choice that would make national headlines nearly four decades later.

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

John E. “Jack” Coons and Stephen Sugarman didn’t use the term “education savings accounts” in their book, “Education by Choice.” But they described a sweeping plan for publicly funded scholarships in terms familiar to those keeping tabs on ESAs. They envisioned parents, including low-income parents, having the power to create “personally tailored education” for their children, using “divisible educational experiences.”

To us, a more attractive idea is matching up a child and a series of individual instructors who operate independently from one another. Studying reading in the morning at Ms. Kay’s house, spending two afternoons a week learning a foreign language in Mr. Buxbaum’s electronic laboratory, and going on nature walks and playing tennis the other afternoons under the direction of Mr. Phillips could be a rich package for a ten-year-old. Aside from the educational broker or clearing house which, for a small fee (payable out of the grant to the family), would link these teachers and children, Kay, Buxbaum, and Phillips need have no organizational ties with one another. Nor would all children studying with Kay need to spend time with Buxbaum and Phillips; instead some would do math with Mr. Feller or animal care with Mr. Vetter.

Coons and Sugarman were talking about education, not just schools, in a way that makes more sense every day. They wanted parents in the driver’s seat. They expected a less restricted market to spawn new models. In “Education by Choice,” they suggest “living-room schools,” “minischools” and “schools without buildings at all.” They describe “educational parks” where small providers could congregate and “have the advantage of some economies of scale without the disadvantages of organizational hierarchy.” They even float the idea of a “mobile school.” Their prescience is remarkable, given that these are among the models ESA supporters envision today.

It's also noteworthy given a rush to portray education savings accounts as right-wing.

In June, for example, the Washington Post described the creation of the near-universal ESA in Nevada as a “breakthrough for conservatives.” School choice would likely be a top issue in the 2016 presidential campaign, the story continued, with leading Republicans like Jeb Bush, Scott Walker and Marco Rubio all big voucher supporters and Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton opposed. The story pointed out Milton Friedman’s conceptualizing of vouchers in 1955, then added, “The idea was long thought to be moribund but came roaring back to life in 2010 in states where Republicans took legislative control.”

It’s true that in Nevada, Republicans took control of the legislative and executive branches in 2014, and then went on to create ESAs. But it’s also true that across the country, expansion of educational choice has been steadily growing for years, and becoming increasingly bipartisan in a back-to-the-future kind of way. Nearly half the Democrats in the Florida Legislature voted for a massive expansion of that state’s tax credit scholarship program in 2010. About a fourth of the Democrats in the Louisiana Legislature voted for creation of that state’s voucher program in 2012. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has been fighting for a tax credit scholarship in that bluest of blue states – an effort in which he’s joined not only by many other elected Democrats, but by a long list of labor unions.

These Democrats are sometimes accused of being sellouts – often by teachers unions and their supporters, who have been especially critical of Cuomo. But the truth is, they can draw on a rich history of support for educational choice grounded in the principles of the American left.

The recent history of ESAs isn’t quite as polarizing as the Post suggests, either. (more…)

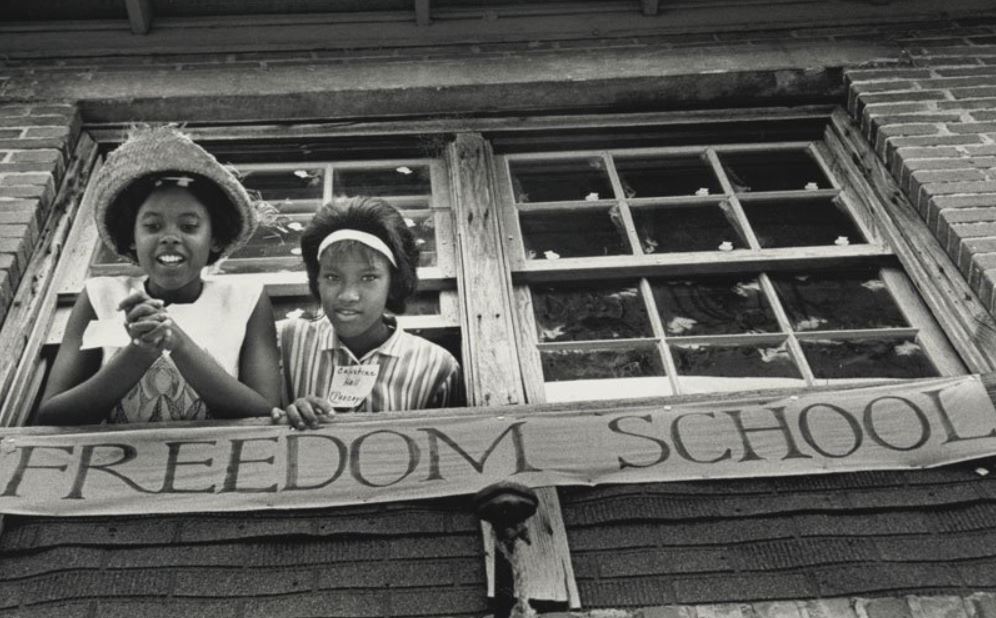

Despite what the story lines too often suggest, school choice in America has deep roots on the political left, in many camps spanning many decades. Mississippi Freedom Schools, pictured above (the image is from kpbs.org), are part of this broader, richer story, as historian James Forman Jr. and others have rightly noted. Next week, we’ll begin a series of occasional posts re-surfacing this overlooked history.

By critics, by media, and even by many supporters, it’s taken as fact: School choice is politically conservative.

It’s Milton Friedman and free markets, Republicans and privatization. Right wing historically. Right wing philosophically.

Critics repeat it relentlessly. Conservatives repeat it proudly. Reporters repeat it without question.

It has been repeated so long it threatens to replace the truth.

The roots of school choice in America run all along the political spectrum. And to borrow a term progressives might appreciate, the inconvenient truth is school choice has deep roots on the left. Throughout the African-American experience and the epic struggles for educational opportunity. In a bright constellation of liberal academics who pushed their vision of vouchers in the 1960s and ‘70s. In a feisty strain of educational freedom that leans libertarian and left in its distrust of public schools, and continues to thrive today.

This is not to deny the importance of the likes of Friedman in laying the intellectual foundation for the modern movement, or to ignore the leading role Republican lawmakers have played in helping school choice proliferate. But the full story of choice is more colorful and fascinating than the boilerplate lines that cycle through modern media. Black churches and Mississippi Freedom Schools are part of the picture. So is the Great Society and the Poor Children’s Bill of Rights. So is U.S. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., and Congressman Leo Ryan, D-Calif., the only member of the U.S. House of Representatives to be assassinated in office.

Perception matters. Perhaps now more than ever. There is no doubt far too many people who consider themselves left/liberal/progressive and identify politically as Democrats do not pause to consider school choice on its merits because they view it as right-wing and Republican (or maybe libertarian). In these polarized times, people have never identified with ideological and party labels so completely, and, I fear, so often made snap judgements based on perceived alignments.

School choice isn’t the only policy realm to suffer from false advertising, but in the case of vouchers, tax credit scholarships and related options, the myths and misperceptions appear particularly egregious. (Note: I work for Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog and administers Florida's tax credit scholarship program, the largest private school choice program in the nation.) The forgotten history means newcomers to the debate get a fractured glimpse of the principles that have long fueled the movement. And it means critics can more easily cast contemporary supporters on the left as phonies or sellouts, as opposed to what they really are: heirs to a long-standing, progressive tradition.

We at redefinED would like to redouble our efforts to change that. So, beginning today, we’re going to offer a series of occasional posts about the historical roots and present-day fruits of school choice that are decidedly not conservative.

We’re calling it “Voucher Left.”

We hope to offer entries big and small, some by redefinED regulars, some by guests. We may rescue a historical document from the dust bin. We may serve up a profile or podcast. Maybe we’ll reconstruct some fascinating but forgotten moments in the rich history of choice, like what happened in California in the late 1970s when a couple of Berkeley law professors tried to get a revolutionary voucher proposal on the statewide ballot. (Here’s a bit of tragic foreshadowing: But for Jim Jones of the People’s Temple, vouchers today might be considered a liberal conspiracy.)

There is no set schedule for the series. We’ll roll out posts as often as time permits, and as often as we can keep digging up good stuff. Look for the first two right after Labor Day.

In the meantime, a few caveats:

We didn’t coin the term “voucher left.” As far as we can tell, all credit goes to writer (and former fellow at the Center for American Progress) Matthew Miller. In a 1999 piece for The Atlantic, Miller used the term to describe the ‘60s era choice camp that included John E. Coons and Stephen Sugarman, Berkeley law professors who co-founded the American Center for School Choice, which helped put this blog on the map. We thought the term perfect – and just as fitting an umbrella for choice’s other progressive pillars. (more…)

by Kevin P. Chavous

When Hillary Clinton announced her presidential candidacy in an online video Sunday, I along with many education advocates were saddened by one of the families featured in her announcement.At the :17 second mark of the video, a mother is featured discussing how her family is moving so her daughter, who is starting Kindergarten in the fall, can attend a quality school. While thought to be an uplifting story, this family’s predicament is something that millions of families across the country face. This family is fortunate enough to be able to move to a better school district; however, many families, especially low-income families, are trapped in their current schools that do not work for their children with no alternatives in sight.

The reality is if Hillary supported school choice, this family would not have to pack all of their belongings and uproot their lives to ensure their child receives a great education. They would be able to attend the school of their choice without making a drastic move or placing more strain on their budget. They would be empowered with the ability to make education decisions for their child without being restricted solely by their ZIP code. (more…)