Science writer Matthew Ridley has described the innovation process as one of trial and error in which individuals combine pre-existing techniques and/or technologies.

Science writer Matthew Ridley has described the innovation process as one of trial and error in which individuals combine pre-existing techniques and/or technologies.

One example: Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing were around for many years before innovators figured out how to put them together to revolutionize the energy market.

Another example: Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” and Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” were around for decades before some unknown innovator combined them to create the greatest song in the English language.

Likewise, a new policy brief posted to the Arizona Charter Schools Association website suggests that combining project-based micro-schools with rigorous live distance learning can create a new path, to scale, for high-demand schools and can unleash new opportunities for teachers while addressing equity concerns with pandemic pods.

A Phoenix radio host interviewed a 44-year (!) classroom veteran teacher last year. The teacher observed that the main problem with education today isn’t a lack of funding, which he said has “always been tough.” The real problem, he said, is that “the joy of teaching has been strangled out of the profession.”

This can and must change, and combining small education communities with rigorous distance learning just might do the trick.

If you’ve ever visited a project-based learning micro-school, you quickly see the joy so sorely lacking in most education settings. With Sal Khan, founder of a free educational video library that allows blending learning, as your scout-troop/school leader, you’re watching an excited group of kids engaging in 3-D print design. An education guide leads students through some daily academic work on computers, but then the students tackle group projects.

I watched students engaged in 3-D print design at a Prenda micro-school on the Apache Nation in San Carlos Arizona. These kids were not just learning, they were learning and loving it. These types of schools have great potential because they do not require educators to raise funds for multi-million facilities.

This style of education, which took an early hold prior to the pandemic, has been thrust into the limelight now through the advent of pandemic pods. Educators can address equity concerns, such as a low-income family’s ability to pay teachers and gain access to computers, with enlightened public policy.

Success Academy of New York developed another innovation to pair with micro-schools. Success Academy changed the roles of instructional staff for distance learning, with teachers variously tackling the roles of lecturers and small group facilitator/student problem solvers.

The most skilled math instructor in the network gave a live internet broadcast lecture via the internet. Students divided into small groups to interact with teachers to discuss the material and work out issues. Teachers then graded and monitored student achievement and scheduled individual online tutoring sessions with struggling students.

The Success Academy distance learning model is itself potentially revolutionary. In theory, the network could offer this version of itself to both enrollment lottery winners and enrollment lottery losers. Many parents on the waitlist might very much prefer this option over a spot in a district that numbers rather than names schools.

Education, however, is very much a social enterprise for many, as most of us want and need access to instructors and classmates. We need community. The Arizona Center for Student Opportunity brief referenced above calls for educators to combine Prenda-style micro-schools with Success Academy-style distance learning programs.

This proposal could take a variety of forms. Education service providers could reach agreements with pandemic pod providers to “adopt” them into their distance learning programs. Alternatively, high-demand schools could gauge interest in creating pods among their current students and their waitlisted families.

Equity-related concerns connected to pandemic pods could be addressed through funding students. Private choice programs focusing on disadvantaged student populations, such as Florida’s scholarship programs, could be used to help low-income students and those with disabilities afford micro-schools. Alternatively, public school distance-learning statues could defer costs.

In Arizona, Prenda operates schools through district, charter and private choice mechanisms. All Prenda students take the state’s AZMerit exam, and students whose education is funded through district and charter mechanisms have their results factored into school ratings.

In partnering with a Success Academy-style distance learning provider, the “mothership” would provide the live lecture, while the small group facilitation function would be conducted by in-person by guides. Different flavors of micro-schools can be created through affiliation with different mothership institutions. Teachers can run the show rather than being part of all-too-often hugely indifferent bureaucracies. All we need are some trailblazing educators and enlightened policy.

To paraphrase the Gen-X bard:

“With the schools out, it’s less dangerous! Here we are now, liberate us! Don’t feel stupid or contagious! Here we are now, educate us!”

Eva Moskowitz, founder and chief executive of Success Academy Charter Schools, has been a teacher, a college professor, an elected official and chair of the New York City Council’s Education Committee.

Sweet are the uses of adversity,

Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head;

And this our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.

I would not change it.

-- As You Like It, William Shakespeare

Brian Greenburg, CEO of the Silicon Schools Fund, produced this graphic to categorize varying levels of proficiency achieved by schools that launched impromptu distance learning at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The graphic accompanied a post Greenburg wrote for EducationNext titled, “What we’ve learned from distance learning and what it means for the future.”

![]() The graphic’s horizontal axis organizes schools by general effectiveness: culture, teamwork, flexibility, quality. The vertical axis organizes schools by expertise with technology, low to high. In the worst-case pandemic scenario, you are a child enrolled in a school system with an ineffective bureaucratic culture and a poor grasp of technology. In the best-case scenario – a highly effective, flexible and technically proficient organization – your school quickly reorganized efforts around distance learning to produce high-quality distance instruction.

The graphic’s horizontal axis organizes schools by general effectiveness: culture, teamwork, flexibility, quality. The vertical axis organizes schools by expertise with technology, low to high. In the worst-case pandemic scenario, you are a child enrolled in a school system with an ineffective bureaucratic culture and a poor grasp of technology. In the best-case scenario – a highly effective, flexible and technically proficient organization – your school quickly reorganized efforts around distance learning to produce high-quality distance instruction.

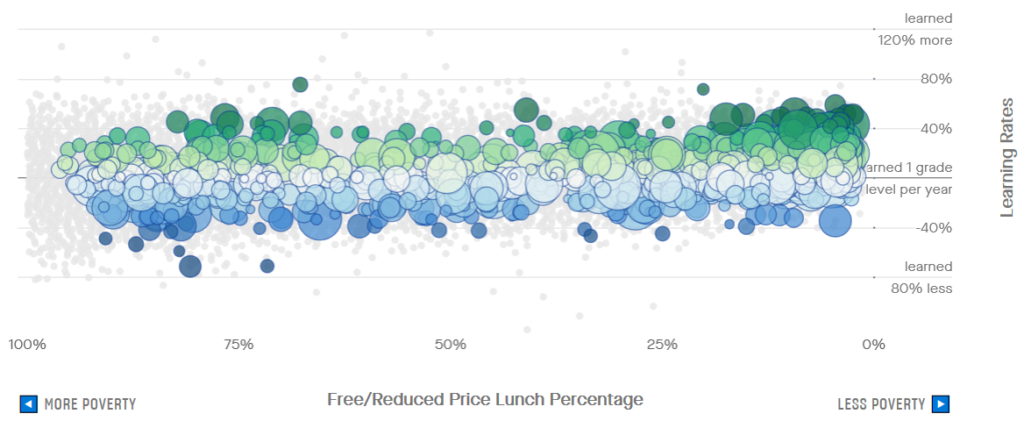

New York’s Success Academy Charter Schools have been lauded for the high levels of academic proficiency achieved by high-poverty students. Stanford University’s Opportunity Explorer, for instance, shows Success Academy schools posting about three grade levels above average in academic proficiency, despite free and reduced-price lunch eligibility in the 74 to 90 percent range. Plotted against all available data in schools nationwide, this means Success Academy is not only breathing some very thin air in terms of performance, but also that it can lay claim to consistent excellent achievement.

The horizontal axis in the Greenburg chart was not an issue for Success Academy, and as it happens, neither was technological dexterity.

How did Success Academy tackle pandemic-induced distance learning? Well, the Philanthropy Roundtable was curious about that, so it interviewed founder and CEO Eva Moskowitz on how the schools rose to the pandemic challenge. You can watch the video here. What Success Academy pulled off seems potentially revolutionary, and Moskowitz is sharing learning resources free of charge.

I’ll give you my CliffsNotes version of the video.

The most effective lecturer in the entire network of schools on any given subject delivered live instructional lectures, while other teachers broke students into smaller groups online to facilitate group discussion and projects. Teachers monitored ongoing assignments to identify students who were falling behind and proactively required students to attend online remedial tutoring sessions.

In other words, Success Academy staff took great effort to keep students on track.

Why is this potentially revolutionary?

Because Success Academy and anyone else mastering these techniques may be able to offer it as an option to both admission lottery winners and losers in the future. It may be possible, for instance, to serve many students currently floundering in the bottom left quadrant in the Greenburg graphic through these techniques.

Exempt from public haunt, and more importantly, the need to provide very costly school space, a new path to quality and scale may beckon.

This crisis version of Success Academy distance learning should be viewed as a mere prototype. Success Academy and others doubtless will improve upon these techniques.

In this episode, Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill interviews Louis Algaze, president and CEO of Florida Virtual School. Founded in 1997, FLVS is a publicly funded non-profit that operates as its own $240 million school district. During the 2018-19 academic year, it served 215,505 students, technically making it the largest public school in the United States.

In this episode, Step Up For Students president Doug Tuthill interviews Louis Algaze, president and CEO of Florida Virtual School. Founded in 1997, FLVS is a publicly funded non-profit that operates as its own $240 million school district. During the 2018-19 academic year, it served 215,505 students, technically making it the largest public school in the United States.

Tuthill and Algaze discuss FLVS’ rapid expansion in the wake of COVID-19 and the role the online school will play going forward, touching on improvement opportunities for the learning model they expect will be an example for the nation’s public school system as it shifts gears into the fall and beyond.

"There is so much talent and desire … We’re looking forward to really fantastic things in the future."

EPISODE DETAILS:

· How FLVS rapidly expanded capacity to serve every public school student in Florida

· Differences between crisis learning and a full online education

· How the demand for blended learning will grow and what it will look like

· The challenge of acclimating nearly 2,000 teachers to a blended learning model and the commitment to train teachers statewide

· Collaborating with traditional public, charter, and private schools to address student needs

LINKS MENTIONED:

· Online school during COVID-19: It’s about student learning (Alaska)

· Florida Virtual School brings online education to Alaska

Earlier this week, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush joined Education Next editor-in-chief Marty West to talk about the lessons he learned dealing with crisis and how those lessons can be applied to the coronavirus pandemic and the challenges it poses for K-12 education.

Among the suggestions Bush offers state and national leaders: Be clear and transparent, connect on a human level, and gather the best possible minds regardless of political persuasion.

“Just as in every disaster or every disruptive time in world history, incredible things happen when you’re forced to do things,” Bush says. “Because you have no other option, generally, you do them.”

Listen to the podcast at https://www.educationnext.org/ednext-podcast-jeb-bush-on-adjusting-to-distance-learning-during-pandemic-covid-19-coronavirus/.

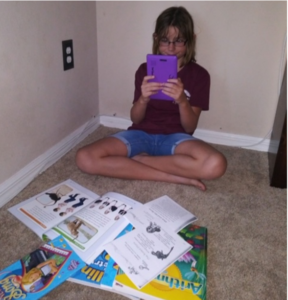

Miley Parks, 10, a fifth-grader at Riverside Christian School in Trenton, Florida, works on a school assignment on her laptop.

As the COVID-19 pandemic forced the statewide shutdown of school campuses, Riverside Christian School principal Ginny Keith knew she’d have to act quickly to develop a game plan for distance learning.

“I didn’t know much about technology,” admitted Keith, principal of the 140-student K-12 school in Trenton, Florida, at the heart of rural Gilchrist County. Half of the students receive a Florida Tax Credit Scholarship for lower-income and working-class families; three attend on a Gardiner Scholarships for students with unique abilities. Both programs are administered by Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.

Keith took a leap of faith and asked for help from what some would consider an unlikely ally: public school district staffers who made it possible for Riverside to be up and running with a distance learning program that included live online instruction.

Joe Mack Locke, who works in IT for the Levy County School District, didn’t hesitate to come to Riverside’s assistance.

“It doesn’t matter if they’re my kids or Dixie County kids or Gilchrist County kids,” Locke told Keith.

Gilchrist County and its closest neighbors, Levy and Dixie counties, form a close-knit rural community where ties are strong, especially among educators. Riverside teacher Donna Goodson-King used to work with Locke in the Dixie County School District and once taught Locke’s daughter at a district high school. She also was married to Locke’s late cousin. So naturally, Goodson-King reached out to Locke when the school needed help.

“Education is a family in itself,” Goodson-King said.

With his school district’s approval, Locke helped set up Riverside’s Google infrastructure. A former colleague of Goodson-King’s from another neighboring county volunteered to teach staff how to use Google resources.

“Educating children is educating children, and we’re going to help them no matter who they are,” said Locke, who spent 17 years working in IT for the Florida Department of Corrections and saw firsthand the consequences of a poor education. “I’m in technology, but my job is to educate children using technology.”

Keith and her team soon were ready to launch. Count parent Judy Parks among the grateful.

“Everything is going pretty smoothly, and everyone is going with the flow,” said Parks, whose son, Kody, 15, and daughter, Miley, 10, attend Riverside, where Parks works as the school secretary.

The school uses a curriculum called Accelerated Christian Education Paces, which allows students to work at their own speed in each subject. Teachers initially gave quizzes along with a pre-test and a test for each unit but dropped the quizzes because they became too much to keep up with. Tests are given orally to remove any temptation for students to be less than rigorously honest.

Each school day, the Parks kids wake up, eat breakfast, make their beds, and then start their school day. Classes at Riverside are self-contained for younger students, while a small team of teachers educate students in higher grades. Attendance is taken by requiring each student to check in with his or her assigned teacher each day by Facebook, text or email.

The method doesn’t really matter, Keith said; turning in assignments also serves as proof of attendance. Those who haven’t been heard from by 3 p.m. each day get a phone call, she added.

Teachers host live teleconferences on Zoom and Google Meet and communicate via text or FaceTime.

“The teachers are available any time throughout the day and that makes it a blessing,” Parks said.

The live instruction has been the biggest hit with the kids.

“They can see one another, and they just get excited to see their friends and be social for a few minutes,” she said.

Locke, who also is a representative for Fellowship of Christian Athletes, isn’t stopping there. He’s now helping Riverside form its own FCA chapter.

“Whether these kids are living in your community, if you’re an educator, you don’t care,” Keith said. “They’re all our kids.”

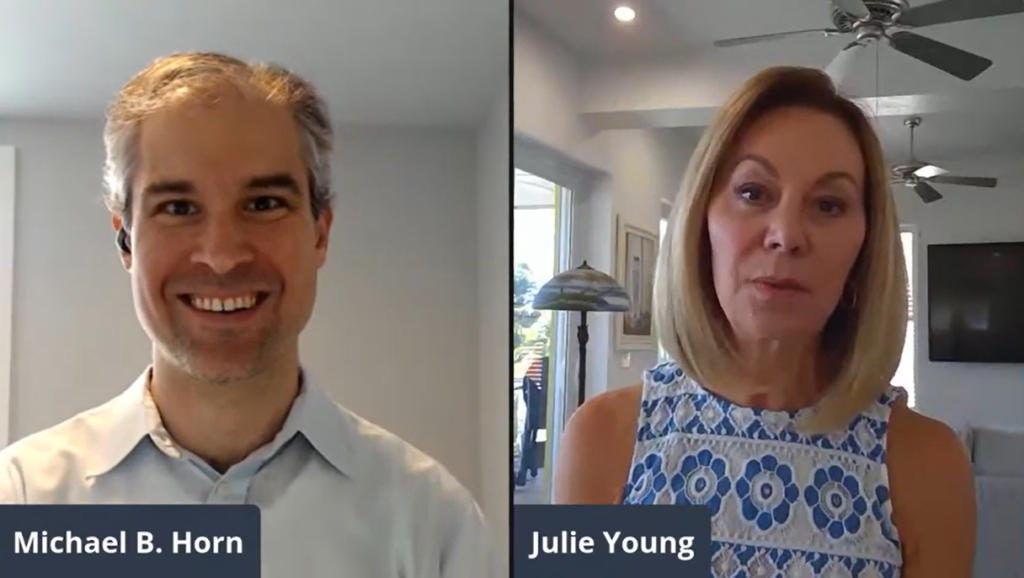

In this video special to redefinED, author and education reformer Michael Horn talks with education pioneer Julie Young, the founder of Florida Virtual School, a student-centered online-learning provider that focuses on competency based education rather than traditional seat time. Julie is now the CEO of Arizona State University Prep Digital, an online high school that offers an accelerated path toward college admission and the chance to earn concurrent high school and university credit.

In this video special to redefinED, author and education reformer Michael Horn talks with education pioneer Julie Young, the founder of Florida Virtual School, a student-centered online-learning provider that focuses on competency based education rather than traditional seat time. Julie is now the CEO of Arizona State University Prep Digital, an online high school that offers an accelerated path toward college admission and the chance to earn concurrent high school and university credit.

Horn and Young discuss the ways in which COVID-19 is a moment for teachers and families to transform learning. They also discuss a new online learning case study Young co-authored that has been published by the Pioneer Institute.

“Right now, it's about the fundamentals. Anything that is remotely filler needs to go away. What are the standards we need to meet to feel as if we have accomplished what we need for this school year? Let's look closely at that and focus our plans around it."

EPISODE DETAILS:

· How Arizona State University moved to full remote learning within 48 hours and the active role the university has taken in lending support to other schools

· What states and school districts should be doing to move from the crisis of shifting to distance learning toward a more stable, sustained distance learning future

· Preparing for a variety of fall schooling scenarios based on the virus’ effect, including continuing full-time remote learning for those who want it

· The benefits of mastery-based education models for students with unique abilities

· Incorporating social and emotional learning into the distance-learning model

LINKS MENTIONED:

ASU for You: Resources for every learner, at any age

Pioneer Institute – Case Study for Transition to Online Learning

Editor’s note: In this commentary, Jawan Brown-Alexander, Chief of Schools for New Schools for New Orleans, proposes that it's possible to take what has been learned from the coronavirus pandemic and use it to reimagine what schools could look like in two, five or even 15 years. The piece originally published April 29 on Education Post.

Editor’s note: In this commentary, Jawan Brown-Alexander, Chief of Schools for New Schools for New Orleans, proposes that it's possible to take what has been learned from the coronavirus pandemic and use it to reimagine what schools could look like in two, five or even 15 years. The piece originally published April 29 on Education Post.

I am a former school leader and a current educational strategist who works with charter leaders from across New Orleans. Together, we have been thinking about the intersection of educational inequity and the disparate impact of COVID-19. With so much instability in our children’s educational experience, we know that high-quality curriculum matters more than ever before. We are considering what to do now to support our children, as well as what comes next.

Scientists continue to work on ways to stop this pandemic—and when they finally do, we will turn the page and look to the future. It’s hard to believe now, but folks will get back to work, restart the economy, and begin to see past this horrifying time in our nation’s history. When we rush back to our lives, however, we will still face the reverberating impacts that are coming from this crisis, especially in our minority communities.

Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley said it best in a recent tweet—“Our Black and brown communities face a crisis within a crisis.” In Louisiana, for instance, while Black residents make up around 30% of the state’s population, as of April 20, 56% of Louisianans who have died from COVID-19 have been Black.

That inequity is not only found in the toll of the virus itself. We will also see an impact on those people of color who faced insecurity in jobs, food or housing even before this moment. And we will see an impact in our education system, too. In Louisiana, as in many states, school buildings will be closed through the end of the school year; the learning loss that normally occurs during the summer is now a real risk even before summer begins. The cost of a slow rollout of distance learning could be significant, and take the greatest toll on children of color.

When the virus hit, schools and districts with mostly White and affluent students could have the confidence that most of their students would be able to fully engage with online distance learning right away. For districts like New Orleans, with mostly students of color and students who are economically disadvantaged, quick efforts to roll out online distance learning faced a significant barrier: Many children lacked the technology needed to connect.

Taking action to keep kids connected and learning

Our district leadership took immediate action to purchase the materials those students needed, but it takes time to procure, safeguard and distribute technology citywide. Many of our students were—and are—also dealing with housing and food insecurity that makes it more difficult to launch and maintain an at-home learning environment.

This is not unique to New Orleans. Across our nation, districts that serve mostly students of color, and those with high rates of economically disadvantaged students, will face a steeper climb than others when it comes to distance learning. But by having a strong, clear distance learning plan, we can make sure closed buildings do not mean closed schools and drastic educational losses.

This means connecting students with technology, if at all possible. It also means continuous engagement with students and families, through the phone, the internet, or both. And it remains as important as ever to provide a high-quality, standards-aligned curriculum. We cannot fully control that students may take in less material than usual right now. We can control whether or not that material is the highest quality it can be.

Many Tier-1 curriculum vendors are providing updated materials for a distance learning context online. Schools can take advantage of this, lowering the lift of translating existing materials for a new kind of delivery. Schools can also continue to provide their teachers with (virtual) professional development around their Tier-1 curriculum, so they can better adjust to this “new normal.”

Academics are only one part of the response

Academics are just one part of this, though. A strong distance learning plan also takes students’ basic needs and mental health into account. During this pandemic, Black and Brown children will lose loved ones at a disproportionate rate compared to their White peers; this will take a deep emotional toll. An incredibly high number of New Orleans’ children had already experienced trauma prior to this event, and this horrible crisis could cause those numbers to increase.

It is imperative, then, that our distance learning plans involve connecting mental health experts, like social workers, to provide support to students, families, and school staff members who have been heavily impacted by this crisis. Resources for physical health care, food, shelter, and more remain critical as well. We can leverage external partnerships to help do so—they are more important than ever. Making certain that students receive vital supports is key to the strength of our community and the growth and health of our students.

We can reimagine what school looks like

We must maintain our focus on the present moment and through the close of the school year. But we must also look even further ahead. There is much we will learn from this crisis—from how to support students experiencing trauma, to how to connect children to local resources, to how to best leverage technology. We can take what we have learned to reimagine what school will look like in the next two, five, or even fifteen years. We can also join in conversations with our families, community members, fellow educators and students themselves about what we will need from federal, state, and local officials as we re-open schools.

Together, we can keep this crisis from digging even wider educational divides. Our children of color already face great inequities. If we focus on distance learning and whole-child support, and keep an eye on the future, we can help keep them safe and learning today and expand their opportunities tomorrow.

Families will remember March 2020 for how quickly state officials closed schools due to the coronavirus outbreak. If schools want to offer parents and children continuity and stability, educators and policymakers must focus in April on jump-starting instruction while students are at home.

Families will remember March 2020 for how quickly state officials closed schools due to the coronavirus outbreak. If schools want to offer parents and children continuity and stability, educators and policymakers must focus in April on jump-starting instruction while students are at home.

Yet some state policymakers are finding new ways to limit learning options during the pandemic. A Portland, Ore., news source, the Willamette Week, said Oregon officials closed brick-and-mortar schools along with full-time virtual schools – “the definition of social distancing,” according to the news site.

Now, state officials are calling for districts to submit distance learning plans by April 13, but as the Wall Street Journal reported, along with at least one virtual school in the state, the Oregon Department of Education is not allowing students to transfer into virtual schools while schools are closed.

Back east, as of April 1, all Pennsylvania schools, including virtual charter schools, are closed “until further notice.” Gov. Tom Wolf even signed a bill that will withhold state spending for new students who enroll in virtual schools.

David Hardy, founder of Boy’s Latin of Philadelphia, said in a webinar last week focused on charter school activities during the pandemic that Philadelphia district administrators told teachers to stop developing online resources.

“Some teachers who, as soon as this thing hit, they were good teachers and were already connected with their classes,” Hardy says. “They didn’t have to wait for somebody downtown to tell them to do that.”

Hardy continued: “What happened, though, was that the [Philadelphia] school district stopped them from doing this.”

Hardy, who also serves as school board chair for Ad Prima Charter School, said his school is not waiting for the state to issue instructions; the school plans to distribute laptop computers to students without devices at home.

“When you look at how people have responded, it’s my opinion that the charter schools are really out front in this, right away,” Hardy said.

As adults scramble to help children adapt to changes brought on by the virus, our K-12 students do not need perfection. But they do need parents and teachers alike to try.

In Maryvale, Ariz., west of Phoenix, teachers at Western School of Science and Technology (WSST) made sure students could use school devices at home while schools are closed. Eighty percent of WSST students speak a language other than English in their homes, and 95 percent qualify for free or reduced-priced meals, said school director Peter Boyle.

Prior to the pandemic, WSST students divided their time between online instruction and interactions with their teachers.

“We have a significantly high degree of technology penetration and familiarity that allows for a pretty quick switch to this remote learning plan,” Boyle said.

His teachers developed a system of academic playlists, where students access instruction in small bits – 1- to 2-minute segments in some cases.

“A playlist is a personalized learning plan,” Boyle said. “Each teacher populates a playlist, which has about 200 minutes of content, from the online learning programs or from reading materials that we can push out to students.”

Students can choose the order in which they complete the work. Additionally, the school is building on its existing routine of part-time virtual instruction now that all instruction must be online.

In South Carolina, the Charter Institute at Erskine is encouraging all schools to take a similar approach and learn from existing full-time virtual schools. The school is building a library of web videos using the virtual schools to help brick-and-mortar teachers adjust, said Vamshi Rudrapati, director of the Institute.

Julie Phillips, 2019 Charter Institute teacher of the year, who is a virtual school teacher, said in an interview that the best solution, even for teachers who are not experienced with online instruction, is to help students continue “to master and build existing skills.”

“Look at it week by week,” Phillips said. “Every subject that we want them to work on for Monday, use it as a checklist. Check it off, then go to the next subject.”

Many teachers, especially in charter schools, are trying to reach students during the virus, and state officials should encourage these efforts. The pandemic forced physical separation on family, work, and school communities, but it shouldn’t separate teachers and students from ingenuity.

HUDSON, Fla. – All four of Patricia Larkin’s kids have special needs, and all were making good progress at HOPE Ranch Learning Academy, a private school known for its equine therapy program. So when the coronavirus pandemic forced the single grandma to briefly veer into homeschooling, she got a little panicky.

“My children have to be on a routine. And when our country came to a halt, we knew something was going to happen with the schooling,” said Larkin, 59, who is raising three grandchildren and a grandniece. “I tried as hard as I possibly could to do the routine, but I’m not a teacher.”

Two things came to Larkin’s rescue: School choice scholarships, which allowed her children to stay at HOPE even though she just got laid off as a property manager. And the school itself.

The HOPE Ranch staff of 43 rallied around a parent-shaped plan to tailor distance learning to their 150 K-12 students, most of them on the autism spectrum.

“We had to re-invent school in a week. Those were 18-hour days nonstop,” said Jose Suarez, the school’s founder and executive director. Given gaps with devices and connections, “We had to come up with a system that was low tech, that could be deployed regardless of whether there was a computer in the home or not, and could be deployed on a daily basis.”

The early result: Rave reviews from parents like Larkin, who called the plan “brilliant.” And high hopes for the next steps, including a virtual version of equine therapy, the school’s main draw.

Lead teacher Ms. Terri, top left, connects with HOPE Ranch students each morning in an online ‘Social Group.’

A key question in the dash to distance learning is the impact on millions of students with special needs. Some school districts, fearful of being sued by parents of students with disabilities for not providing equitable services, have put a hold on learning for all students. Others are moving ahead, but in ways that aren’t making parents of students with disabilities happy. This is hard, tangled terrain.

In Florida, a national leader in education choice, it remains to be seen whether charter schools or private schools do any better. Those 2,600-plus schools, serving 700,000 students, aren’t getting much coverage. Even if they were, it’s risky to draw generalizations from a few schools, given how diverse those sectors are, and how varied the challenges for students with disabilities.

Florida, though, does present a unique window. It has long offered learning options to parents of students with disabilities. In 1999, it created the McKay Scholarship, a voucher for students with disabilities that now serves 30,000 students a year. In 2014, it created the Gardiner Scholarship, an education savings account for students with special needs that’s now serving more than 13,000 students. (It’s administered by nonprofits like Step Up For Students, which hosts this blog.)

Those scholarships help support a growing number of private schools that serve students with special needs, some of them exclusively. HOPE Ranch, nestled on an oaky stretch of sand hill an hour north of Tampa, is one of them.

Suarez said his team started discussions about remote learning in early March. But they kicked into high gear on March 13, when Gov. Ron DeSantis essentially ordered all public schools in the state to close. Staff quickly surveyed parents about digital capacity, and while not every family had enough computers or tablets for every child, they had phones that could suffice in the short term.

HOPE also asked parents to list their biggest concerns, and the parents were clear. We don’t want our kids falling behind, academically or socially. We don’t want them on computers all day. We don’t want to be their teachers.

The HOPE staff fashioned their plan on that input. Individualized learning packets would be distributed every week. Parents would be given a general schedule with deadlines, but with enough flexibility to figure out the best track for their kids. Using Google Hangouts, teachers would do a half-hour visual chat with each student at a set time every day.

The vast majority of Florida students returned to “school” on Monday, March 30. On Thursday and Friday of the prior week, HOPE teachers did trial runs with the chat platform. By Sunday night, Larkin’s kids were giddy. “They were, ‘I can’t wait! I can’t wait!’,” she said. “They knew they were going to see their teachers.”

HOPE Ranch student Nicole connects with her teacher during a half-hour visual chat they have every morning.

Larkin’s boys – Chad, 12, and Jordan, 7 – are both autistic. Her girls – Bryanna, 10, and Nicole, 10 – are both diagnosed with ADHD and PTSD. All four struggled in public schools. But at HOPE, Larkin said, their teachers know their specific challenges, and work diligently on specific remedies. Jordan, for example, used to avoid “circle time” with classmates because of extreme shyness. But rather than trying to force him to conform, his teachers let him stay back until he felt comfortable. Eventually, he joined on his own.

Bryanna has struggled with maintaining focus. So how sweet it was, Larkin said, that on her first chat on her first day back, Bryanna stayed locked in. “I thought I was in the Twilight Zone,” Larkin said. “They engaged like they were person to person in front of each other.”

HOPE teacher Kevin Trevithick said for his 13 high school students, the quick shift to distance learning has been a lesson unto itself.

“It’s time to adapt and move forward,” he said. “That’s the biggest thing I’ve tried to convey to them.”

One student is resisting the chats, said Trevithick, a former public school teacher, but the others are having fun with the novelty of the situation and the new technology. One told him he’s not a morning person, and now that he can set his own schedule, he’s getting more done.

Can this new way of “school” work for long? Trevithick said some students may get tired of being cooped up. But “people are incredibly adaptable,” he said. “If it’s something where this is the way it has to be, then I do think the majority of them will do just fine.”

The can-do attitude is infectious. Parents like Larkin are having to quickly navigate platforms and apps they never heard of, like Calendly and Adobe Scan. But when they learn they can do it, she said, the next challenge looks a little less daunting.

In the meantime, more programming is coming. On Friday, HOPE is rolling out “virtual chapel” and a virtual social skills class, which will allow the students to stay connected and interact. On Monday, it will begin online speech, occupational and ABA therapy, led by local district employees assigned to the school.

Monday is also the kickoff for the “Virtual and Interactive Horsemanship” class. HOPE students learn to ride, groom and care for a stable of horses. Along the way, they learn teamwork, resourcefulness, problem solving – and get some boosts for their self-esteem. Larkin said the horses helped Jordan, her youngest, come out of his shell. “He mounts those horses … and he’s beaming,” she said. But can it possibly work wonders when it’s online?

It’s working with her kids in the other settings, Larkin said.

So why not?

Lead photo: Bryce, a student at HOPE Ranch, connects with his teacher, Ms. Suzanne, and his parents who joined from remote locations.

One of Arkansas’s top school choice advocates, Laurie Lee, is on the road this month in her home state, visiting 28 cities in four weeks to spread the gospel of education reform.

Arkansas ranked No. 5 among states in an Education Week report that gave it a B- overall. The national average was a C.

But look closer at the findings, said Lee in a phone interview, as she headed toward Mountain View. Arkansas netted a D for its K-12 achievement. Its graduation rate is 70 percent. And of those students who do graduate, 18 percent aren’t ready for college coursework, Lee said.

“Overall, our state’s economy is waning,’’ she said. “We’re losing jobs and foreclosure is high. And you can tie it all back to education.’’

That’s what led Lee to organize The Arkansas Reform Alliance or TARA, a grassroots nonprofit coalition that represents parents, educators and community leaders who want to increase school accountability and improve student success.

Expanding school choice is high on its list.

“We need more options,’’ said Lee, the alliance’s executive director. Her daughters were enrolled in public schools before she switched them to private, virtual and home education in search of the best fit.

Arkansas is home to 18 open enrollment charter schools and 14 district-conversion charter schools, public schools that were converted into charter schools, according to the state Department of Education website.

But to Lee’s group and others, that’s nowhere near enough. They want fewer restrictions on public school transfers. They want more charter and virtual programs. And they want tax-credit scholarships and vouchers. (more…)