**SPOILER ALERT! DO NOT READ IF YOU ARE UNDER THE AGE OF 8**

Western cultures, for some strange reason, involve rituals where we pretend that various “fairy creatures” exist, particularly with children: the Tooth Fairy, a jolly old elf with flying reindeer who brought me an awesome Big Wheel in 1973, egg and goody hiding rabbits, etc. When I became a parent, I played along with these rituals, but then at some point questioned why I was doing it. On the one hand, I didn’t want my children to be those killjoy types who went around bursting the bubbles of other kids. On the other hand, I did not want to train my children not to trust me. I decided to allow the “fun” to go on until they each reached a certain age, then to explain to them that these things are traditions and that it would be best to allow their friends to figure it out on their own.

So, dear reader, I assume that you have reached a certain age and that you are prepared to know the truth about the last fairy creature. Belief in this one tends to persist much longer than the others and is alas, more detrimental. Sorry to be a killjoy, but here goes:

Philosopher kings are not real.

This was my main thought upon reading Mike McShane’s recent entry in a debate about school choice regulation. Go read it. I’ll wait here.

Go on…

Okay, good. My favorite part involved the Gilded Age meat baron, but McShane made several crucial points. Local school boards, state governments and the federal government all regulate public schools in a very active fashion. I could produce multiple graphs from NAEP, PISA, etc., showing what a pig’s breakfast American academic achievement has become, but you have already seen them, so I will spare you. Why are American schools so wretched despite so much regulation? Oh well, that is simple: regulation is not made by philosopher-kings but rather by politics. Politics has an amazingly consistent record of fouling things up.

The philosopher-king fairies, invented by Plato, are a specially trained and educated aesthetic elite who, disinterested in fame or wealth, love only wisdom and justice. Having thus earned the right to rule over us lesser mortals, we proles should feel deferential and deeply grateful for their sacrifice. Again, sorry to burst your bubble, but these people do not exist in the real world. Out here in the real world, mere humans with all kinds of motivations (political and otherwise), limits to their knowledge, greed, stupidity and other normal human failings create regulations. Those of us fortunate enough to live in a democracy get the chance to throw the bums out when we’ve had enough. Just in case you haven’t noticed, a major subtext of politics these days involves bums that voters can’t throw out.

Politics, not philosopher-kings, runs regulation, and politics runs on self-interest far more than on benevolent technocratic wisdom. Choice programs must cope with powerful organized interests that yearn to use regulation as a tool to domesticate choice opportunities and find it in their self-interest to do so. The default position of choice supporters should therefore be to view the calls for regulation with a deep skepticism; it is not paranoia when people really are out to get you.

None of this is to say that it is possible to pass choice legislation without regulation; it is not. I am not aware of any program anywhere that operates without some degree of regulation. American parents, however, want a radically different K-12 system than the one government forces them to pay for (see above). The way forward is to allow families to partner with educators to sort through new schools and education methods. Heavily regulated choice systems might get to something close to the K-12 system parents want and deserve before the heat-death of the universe, but then again, they might not.

America’s founders fought a grueling war against the most powerful country in the world based upon what was then a radical idea, that people could live better without royalty to boss them around. The divine right of kings was another myth humanity needed to grow up and discard, and that should include philosopher-kings.

Last week, I had the opportunity to make a presentation about how lawmakers can support teachers who want to start their own schools. The four key features:

2. Formula funding/demand-driven funding: Whoever applies for a choice program should receive funding if eligible.

3. Avoidance of anti-competitive accreditation requirements: Don’t ask your startup schools to operate without funding from the choice program while incumbent/accredited schools receive choice funding.

4. Exempt private schools from municipal zoning: Old hat for charter schools, needed for private schools as well.

Florida is the only state your humble author is aware of that has taken all four of these steps. This makes Ron Matus’ new study "Going With Plan B” all the more important. Despite a statewide increase of 705 private schools, 41,000 Florida families applied for, received, and ultimately did not use an ESA. Matus surveyed thousands of these parents to learn why.

The lack of school space was the No. 1 reason Florida families found themselves as non-participants. Reasons two and three were related to costs, which can also be thought of as a supply issue.

The “Going with Plan B” study is very interesting and should be studied carefully by Florida policymakers. For now, however, let us focus on the other states with choice programs that lack the four critical elements listed above. If FLORIDA has a supply issue, your state, sitting at one out of four, or two out of four, should take note: It is likely to be even worse in a state near you.

Last week, the Heritage Foundation released a study from yours-truly called From Mass Deception to Meaningful Accountability: A Brighter Future for K–12 Education. The basic argument: the good intentions of the No Child Left Behind era were completely undermined by opponents, who both defanged state rating systems and tamed charter school laws. On the first assertion, I offered charts like:

Ooof, and even worse this comparison between Arizona’s school grades in Maricopa County and GreatSchools private ratings for schools within 15 miles of Phoenix (the closest approximation on the GreatSchools site) after converting the GS 1-10 ratings onto a A-F scale:

Charter schools always and everywhere had waitlists, ergo, accountability amounted to “trophies for everyone” state systems and charter school sectors that never matched demand with supply. Take a look at the above chart, however, and you’ll see that GreatSchools is a much, much tougher grader than the state of Arizona. The usual suspects have a much tougher time undermining private rating organizations, and they gather reviews (which research shows families value). Ergo the backgrounder makes the argument that we should not rely upon state rating systems in preference to the already superior, more trusted and versatile private efforts. Furthermore, we should expand rating systems into the broader universe of education service providers active in today’s ESA and robust personal use tax credit programs, specifically to gather reviews accessible to families for purposes of navigating the wide world of choice, which we need much more of.

Okay so a couple of reader requests. First, I was asked if I could create something like the Phoenix chart for a district in Florida. I chose Miami:

So not as much of a contrast as Arizona but…if I were looking for a school in Miami, I would look at GreatSchools.

Next, I received a request about this chart from Sandy Kress:

Putting the NAEP improvement numbers in context: In the 2024 NAEP, the total across the four mathematics and reading exams between the highest scoring state (MA) and the lowest scoring state (New Mexico) was 10%. So, the nation-leading 5% improvement in Mississippi scores should be seen as meaningful. Sandy asked me to look at an earlier period from the mid-1990s until 2011 rather than the 2003 to 2019 period, as his contention was that that period saw a lot more academic improvement before the federal law was defanged on a bipartisan basis during the Obama administration.

All states began taking NAEP in 2003, so stretching back to the 1990s loses a number of states. Also, 1996 didn’t include the two reading tests, so I substituted 1998. Nor can we automatically attribute the trends exclusively to standards and accountability (other things also going on), but Sandy is correct that NAEP showed a lot more academic improvement during those earlier years:

Accountability hawks/the federal government may have indeed coaxed more productivity out of the public school system. Then on a bipartisan basis, Congress removed federal pressure (passed the Senate 85-12 and the House 359-64). Subsequently a large majority if (perhaps?) not every single state merely went through the motions of “accountability” with trophies for (almost) everyone. Kress can justifiably look at these data to claim, “the juice is worth the squeeze” and I can look at the same data to say, “academic transparency is too important to leave to politicians and their appointees.”

Franklin Roosevelt noted ““It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But try something.” Every state in the union remains entirely free to adopt tough accountability practices, but apparently few if any have chosen to do so. The next something to try in my opinion are enhanced private rating systems and robust choice programs. Temporarily semi-tough accountability systems run by states and charter school waitlists ultimately proved to be a strategy with limited political sustainability.

Gevrey Lajoie visited a School Choice Safari event to learn about options for her son, Elijah. The event was sponsored by GuidEd, one of the many organizations springing up in states that have granted parents the flexibility to choose the best educational fit for their children.

TAMPA, Fla. — Parents, many pushing babies in strollers with school-age children in tow, made their way through the covered pavilion as they surveyed the brightly decorated tables representing 28 local schools.

Their goal: To gather as much information as possible as they try to figure out the best educational fit for their children, either for the 2025-26 school year or beyond.

“We’re all over the place with which school,” said Gevrey Lajoie of South Tampa. Her son, Elijah, is only 3, but she said it’s not too early to begin looking at options. A mom friend told her about the School Choice Safari at ZooTampa at Lowry Park. It would give her a chance to check out many schools all in one place and learn about state scholarship programs.

Lajoie isn’t alone. For this generation of Florida families, gone are the days of simply attending whatever school they’re assigned based on where they live. Families actively shop for schools; schools actively court them, and districts perpetually create new programs.

And while the benefits are clear, some families end up feeling adrift in a sea of choices.

New organizations are springing up to help families find their way. "A variety of options are out there, and the number is growing, but families don’t know how to navigate them. There was no place for them to go to get help,” said Kelly Garcia, a former teacher who serves on Florida’s State Board of Education.

New organizations are springing up to help families find their way. "A variety of options are out there, and the number is growing, but families don’t know how to navigate them. There was no place for them to go to get help,” said Kelly Garcia, a former teacher who serves on Florida’s State Board of Education.

In 2023, the Tampa Bay area resident and her brother-in-law, Garrett Garcia, co-founded GuidEd, a nonprofit organization that provides free, impartial guidance to help families learn about available options so they can find the best fit for their children.

The organization hosts a bilingual call center where families can get information about all options in Hillsborough County, from district and magnet schools to charter schools, private schools, religious schools, online schools and even homeschooling. GuidEd also helps families sift through the various state K-12 scholarship options. The group also hosts live events, such as the School Choice Safari, to connect families and schools.

Organizations are cropping up all over the country, especially in areas with lots of choices. Their specific missions and business models vary, but they are united by a common theme: They help families navigate an evolving education system where they have the power to choose the best education for their children

Jenny Clark, a homeschool mom and education choice advocate, saw the need for a personal touch in 2019 when she launched Love Your School in Arizona.

“One of the most important aspects of our work is knowing how to listen, evaluate, and support parents who want to talk to another human about their child's education situation,” said Clark, who had seen parents struggle with the application process surrounding the state’s new education savings accounts program. The program has since expanded to West Virginia and Alabama.

Clark’s nonprofit provides personalized support through its Parent Concierge Service, which offers parents the opportunity for phone consultations with navigators. Love Your School also provides free online autism and dyslexia guides and details about the legal rights of students with disabilities, and it hosts an online community where parents can get support.

“Our services are unique because we pride ourselves in being experts in special education evaluations and processes, which are required for higher ESA funding, public school rights and open enrollment, experts in the ESA program law and approved expenses, and personalized school search and homeschool support,” Clark said.

Kelly Garcia, GuidEd’s regional director, has hosted several in-person events that feature free snacks, face painting, magicians, and prize giveaways in addition to booths staffed by schools and other education providers. During the recent event, parents could visit a booth to learn more about the state’s K-12 education choice scholarship programs.

Garcia, whose organization prioritizes neutral advice about all choices, including public schools, advises parents to start by assessing their child’s needs and then identifying learning options that would best serve them. GuidEd’s philosophy is to trust parents to determine the best environment for their kids.

At the School Choice Safari, families got to check out private schools, magnet schools and charter schools.

“There’s a school out there for everyone,” she said.

Students at New Springs Schools, a STEM charter school that serves students ages 5-14, show off some recent class projects at the School Choice Safari in Tampa.

During the zoo event, Garcia personally escorted parents with specific questions to the tables where they could get answers.

One of them, Hugo Navarro, recently moved to Tampa from Southern California to start a new job for a national investment firm. His wife, who had remained with their three kids in California, had already started researching schools online, but Navarro wanted to get an in-person look at providers and learn more about state education choice scholarships before their 7-year-old son starts school in August.

On his wish list: academic rigor, a focus on the basics, and a diverse student body.

“Academic ratings, that’s our number one thing,” he said.

A Catholic school that offers academic excellence was also a contender, though a secular school wouldn’t be a dealbreaker if it had a reputation for strong academics.

Garcia and Clark both said that as new generations of parents grow more comfortable selecting education options, they see the navigators’ role becoming more relevant, not less.

“Parents can use online tools like google to search for schools, but the depth of what parents actually want, and our highly trained knowledge of a variety of educational issues means that as choice programs grow, the need for our parent concierge services will continue to grow as well,” Clark said. “There are exciting times ahead for families, and those who support them.”

As the number of schools and a la carte learning options grows, Garcia said, families will need information to better customize learning for their children.

“This is a daunting task, even for the most seasoned parents,” she said. “At GuidEd, we see a growing need for unbiased education advisers to ensure a healthy and sophisticated market.”

Garcia compared the search for educational services to buying a home.

“A family is not likely to make a high-stakes decision, like buying a home, by relying on a simple Zillow search,” she said. “Instead, they use the Zillow search to help them understand their options and then rely on a Realtor to help guide them through the home- buying process, relying on their trusted, yet unbiased expertise. We see ourselves as the "Realtor" in the school choice or education freedom landscape.”

Public education in the United States is transitioning from its second to third paradigm.

Paradigm shifts in public education occur when larger societal changes force public education to change to meet these new conditions. Current technological advances and the accompanying social changes are pushing public education into a new paradigm and a third era.

To best meet society’s current and future needs, this third paradigm aspires to provide every child with an effective and efficient customized education through an effective and efficient public education market.

A paradigm: The lens through which communities do their work

In his 1962 book, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” Thomas Kuhn described a paradigm as the lens through which a community’s members perceive, understand, implement, and evaluate their work. A paradigm includes a set of assumptions and associated methodologies that guide how communities construct meaning and determine what is true and false and right and wrong.

A paradigm shift occurs when inconsistencies, which Kuhn called anomalies, begin to occur, and some community members begin to question their paradigm’s veracity and effectiveness. As these anomalies accumulate, community members begin proposing new ways of understanding and implementing their work and a prolonged contest emerges between the existing paradigm and proposed new paradigms. If a majority of the community ultimately decides a new paradigm enables them to resolve the anomalies and better understand their discipline, this new paradigm is adopted. In scientific communities, Kuhn calls these paradigm shifts scientific revolutions.

Paradigm shifts are disruptive and revolutionary because they require community members to reinterpret all their previous work and adopt new ways of conducting and evaluating their future work. Senior community members are particularly resistant to changing paradigms because their status comes from applying the existing paradigm over many years. Consequently, paradigm changes are rare and require several decades to complete.

Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (GTR) was a new physics paradigm that challenged Newtonian mechanics and Newton’s law of universal gravitation (i.e., the dominant physics paradigm at the time). It took over 40 years before GTR gained wide acceptance among physicists. Einstein never won a Nobel Prize for GTR because the Swedish physicists on the Nobel committee refused to accept his new paradigm.

Although Kuhn’s work focused on the role of paradigms in scientific communities, his description of how paradigms function and change is relevant for all communities, including public education. The struggle in U.S. colonial times to transition from a monarchy to a democracy was a paradigm shift. It was a revolutionary change in how government works, was fiercely resisted by those in power, and took decades to complete.

Public education’s first paradigm

Public education’s first paradigm began before the United States was a country, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the “Old Deluder Satan Act” to ensure the colony’s young people learned scripture. As the name of that early legislation implies, this first era prioritized basic literacy and religious instruction. Most children were homeschooled, and formal instruction tended to be ad hoc, improvised, and organized around the agricultural calendar.

Religious organizations provided most of the structured instruction outside the home in the 1700s and early 1800s. Children and adults attended Sunday schools, and communities organized what today we would call homeschool co-ops, which allowed rural children to receive instruction when their chores permitted.

The federal government supported public education through the U.S. Postal Service by subsidizing the distribution of magazines, pamphlets, books, almanacs, and newspapers, and establishing post offices in rural communities. By 1822, the U.S. had more newspaper readers than any other country.

Public education’s first paradigm started failing in the early 1800s as innovations in transportation and communications began connecting the country and promoting more industrialization and urbanization. About 90% of Americans lived on farms in 1800, 65% in 1850, and 38% in 1900.

This transition from rural to urban created childcare needs. Increased industrialization necessitated a more highly skilled workforce. And concerns about social cohesion grew as the growing country welcomed immigrants from Ireland and later from Southern and Eastern Europe. These were demands the informal, decentralized, and family-driven first public education paradigm was ill-equipped to meet.

Public education’s second paradigm

In 1852, Massachusetts passed the nation’s first mandatory school attendance law. This accelerated public education’s shift from its first to second paradigm.

The massive influx of European immigrants beginning in the 1830s was a primary reason Massachusetts decided to make school attendance mandatory. The U.S. experienced a 600% increase in immigration from 1840 to 1860 compared to the prior 20 years. Most of these immigrants were illiterate, low-income, and Catholic. Massachusetts’ mandatory school attendance law was intended to help turn these new immigrants into “good” Americans, meaning they needed to be literate, financially self-sufficient, and well-versed in Protestant theology.

Protestant hostility toward Catholic education in the U.S. continued deep into the following century and included the infamous Blaine Amendments that many states adopted in the late 1800s to forbid public funding of Catholic schools, and the 1922 constitutional amendment in Oregon that required all students to attend Protestant-controlled government schools.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Oregon amendment unconstitutional in its 1925 decision Pierce v. Society of Sisters, ensuring every American family had the right to choose public or private schools for their children. This ruling would later help make public education’s transition to its third paradigm possible.

By 1900, 31 states had passed mandatory school attendance laws. While these laws were not initially well enforced, they did significantly increase school attendance, which created management challenges.

As David Tyack chronicles in “The One Best System,” a history of how this first paradigm shift unfolded in America's cities, a new class of professional administrators, known as schoolmen, set out to modernize public education practice and infrastructure. One-room schoolhouses serving students were no longer adequate, so public education began adopting the mass production processes that enabled industrial manufacturers to create large numbers of products at lower costs. The most famous example was the assembly line that Henry Ford created to mass produce affordable Model Ts.

This new industrial model of public education replaced multi-age grouped students with age-specific grade levels that functioned like assembly line workstations. Just as Ford’s assembly line workers were taught the skills necessary for their workstations, public school teachers were trained to teach the skills associated with their assigned grade level, and children were moved annually from one grade level to the next en masse.

Mississippi became the last state to pass a mandatory school attendance law in 1918. By then the bulk of multi-aged one-room schools were being replaced with larger schools that reflected the best practices of 19th century industrial management. This was the paradigm through which government, educators, families, and the public were now seeing and understanding public education. This change marked U.S. public education’s second paradigm.

Ford famously told customers they could have any color of Model T they wanted provided it was black. Public education adopted this one-size-fits-all approach to increase efficiency. Car consumers began demanding more diverse options over the next several decades, and so did public education consumers. The auto industry diversified its offerings much quicker than public education because it faced competitive pressures the public education monopoly did not. But in 1975, President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, which required all school districts to begin adapting instruction to serve special needs students. This was the first instance of government requiring public education to provide a large group of students with customized instruction.

Public education’s third paradigm

This expansion of instructional diversity accelerated in the late 1970s and early 80s as school districts started creating magnet schools to encourage voluntary school desegregation. The school district in Alum Rock, California even experimented with a short-lived voucher program that fostered an ecosystem of small, specialized learning environments that today would be called microschools.

Most of the beneficiaries of early magnet schools were white middle-class and upper middle-class families who were attracted by the additional resources and high-quality specialized instruction. But magnet schools created for desegregation could serve only a limited number of students. In response to political pressure from influential constituents, school districts began creating magnet schools unrelated to desegregation, which expanded and normalized specialization and parental choice within school districts and accelerated the transition to public education’s third era.

Florida added significant momentum to this transition with the passage of its 1996 charter school law, the founding of the Florida Virtual School in 1997, and the 2001 creation of the nation’s largest tax credit scholarship program.

Two decades later, the COVID-19 pandemic further hastened public education’s current paradigm shift. Magnet schools, virtual schools, charter schools, homeschooling, open enrollment, homeschool co-ops, and tax credit scholarship programs were already expanding nationally when COVID arrived in March 2020. The pandemic turbo charged the growth of these options and newer options such as microschools, hybrid schools, and education savings accounts (ESAs).

Just as 19th century innovations in communications, transportation and manufacturing led to public education’s first paradigm shift, the rise of digital networks, mobile computing, and artificial intelligence are transforming all aspects of our lives, including where and how we work, communicate, consume media, and educate our children. These technical and societal changes are driving a decline of trust in institutions that no longer enjoy a monopoly on public information. They are also driving increased demand for flexibility to determine when, where, and with whom teaching and learning happen. Public education has begun to adopt a paradigm more aligned to 21st century demands, which include parents gaining more power to decide how their children learn.

Government’s changing role

Government’s role in public education will be impacted by a new public education paradigm that reflects these ongoing technical and cultural changes. Under the second paradigm, government had a near-monopoly in the public education market. This quasi-monopoly undermined public education’s effectiveness and efficiency because it failed to take full advantage of the knowledge, skills and creativity of students, families and educators.

In public education’s third era, government will regulate health and safety and help facilitate support services for families and educators but will no longer be the dominant provider of publicly-funded instruction. This regulatory and support function is like the role government currently plays in the food, housing, health care, and transportation markets. Most of the responsibility for how children are educated will shift from government to families and the instructional providers families hire with their children’s public education dollars.

Shifting government’s primary role from instructional monopoly to market regulator and supporter will require operational changes. Families will be able to choose from a plethora of instructional options and will need access to information that allows them to make informed decisions, as well as education advisers who can help them evaluate their child’s needs and develop and implement customized education plans to meet these needs. Government will need to ensure data accuracy and truth in labeling – much as it currently ensures food labels accurately describe what’s in the package.

Third paradigm issues

Providing each child with a high-quality customized education through a more effective and efficient public education market will require public education’s stakeholders to rethink all aspects of how it operates. Here are some issues we will need to address.

Public education’s third paradigm has old roots

In 1791, Thomas Paine proposed an ESA-type program for lower-income children in “The Rights of Man.”

“Public schools do not answer the general purpose of the poor. They are chiefly in corporation towns, from which the country towns and villages are excluded; or if admitted, the distance occasions a great loss of time. Education, to be useful to the poor, should be on the spot; and the best method, I believe, to accomplish this, is to enable the parents to pay the [sic] expence themselves.”

Paine’s recommended funding method was, “To allow for each of those children ten shillings a year for the expence of schooling, for six years each, which will give them six months schooling each year, and half a crown a year for paper and spelling books.”

Over 150 years after Paine’s proposal, Milton Friedman proposed a similar but more comprehensive plan in 1955. Many of the third paradigm’s core ideas existed in the 1700s prior to the industrial revolution. But they were not technically or politically feasible.

Thanks to modern technology and a growing acceptance of families’ rights to direct their children’s education, these ideas are viable today. We can now provide every student with an effective and efficient customized public education. While all students will benefit from customized instruction in a more effective and efficient public education market, lower-income students will benefit the most because they have historically been the most underserved by the current government monopoly. Underserved groups always benefit greatly when the markets they rely on for essential goods and services are more effective and efficient.

Public education’s transition to its third paradigm is happening faster in Florida than in other states. Over 500,000 students using ESAs is rapidly improving Florida’s public education market. Floridians are seeing in real time the creation of a virtuous cycle between supply and demand. More families using ESAs is encouraging educators to create more innovative learning options, which in turn is causing even more families to use ESAs, which in turn is causing even more educators to create more learning options. These rapidly expanding options increase the probability that all students, but especially lower-income students, can find and access learning environments that best meet their needs.

Public education’s first paradigm shift took about 100 years to complete (1830-1930). This second transition began around 1975 and will likely also take about 100 years to complete nationally. Like all paradigm changes, this one is proving to be a long slog. But larger societal changes will help ensure this transition’s success.

The story: Students with disabilities and English language learners were poorly served before the pandemic and will need urgent, long-term help to recover from learning losses, according to a report from the Center for Reinventing Public Education.

The Arizona State University think tank released its annual State of the American Student report today, with a bit of good news but mostly bad news.

“Our bottom line is we’re more worried at this point than we thought,” said Robin Lake, the center’s executive director. “COVID may have left an indelible mark if we don’t shift course.”

The good: Students are bouncing back in some areas. The average student has recovered about a third of their pandemic-era learning losses in math and a quarter in reading.

States and districts nationwide have implemented measures like tutoring, high-quality curricula, and extended learning time, and more school systems are making these strategies permanent. Florida, which offers the New Worlds Scholarship for district students struggling in reading and math, is on a list of states lauded for providing state-funding for parent-directed tutoring.

Rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness of tutoring at helping students catch up.

Rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness of tutoring at helping students catch up.

Education systems across the country – as well as students and families – are starting to recognize the value of flexibility. “As a result, more new, agile, and future-oriented schooling models are appearing.”

That includes microschools and other unconventional learning environments, which are multiplying to meet increasing parent demand.

The bad: These proven strategies aren’t reaching everyone. The recovery is slow and uneven. Younger students are still falling behind. Achievement gaps are also widening with lower-income districts reporting slower recoveries. And the positive studies that show tutoring’s massive boosts to student learning tended to operate on a small scale. Making high-quality academic recovery accessible to every student remains an unmet challenge.

Districts face “gale-force headwinds,” including low teacher morale, student mental health issues, chronic absenteeism, and declining enrollment.

The ugly: The report singled out services to vulnerable student populations for a special warning. The report said this group, poorly served before the first COVID-19 infection, suffered the most. Evidence can be found in skyrocketing absentee rates and academic declines for English language learners.

Special education referrals also reached an all-time high, with 7.5 million receiving services in 2022-23. The report attributed some of this to the pandemic’s effects on young children, especially those in kindergarten who were babies at the pandemic’s onset, but other factors, such as improved identification techniques and reduced social stigma around disability, are also at play.

In short, school systems face larger numbers of students requiring individualized support than ever before.

‘Heart-wrenching struggles’: While some families adapted well, most parents reported difficulty getting services for their children with unique needs. Schools were often insufficient in their outreach. Even the most proactive parents reported difficulty reaching school staff, the report said. Parents who were not native English speakers also had the additional burden of trying to teach in a language they were still learning.

“Many families said schools didn’t communicate often or well enough, and many parents felt blindsided when they found out just how far behind their child had fallen,” the report said.

Recommended fixes: Schools should improve parent communication. The report called for schools to “tear down the walls” by adding schedule flexibility to ensure students’ special education services don’t conflict with tutoring and adding more individual tutoring and small-group sessions. It said schools should also seek help from all available sources, including state leaders, advocates and philanthropists. Schools should also prioritize programs such as apprenticeships and dual enrollment to prepare students for life after graduation.

How policymakers can help: The report urged policymakers to gather deeper data on vulnerable populations so problems can be identified and corrected; provide parents with more accurate information about their children’s progress and offer state leaders a clearer picture of whether those furthest behind are making the progress they need, and help teachers use AI and other tech tools to engage students with unique needs.

The report urged policymakers to place more control in the hands of families by making them aware of their right to compensatory instruction or therapies for time missed during school closures. It also advocated offering parents the ability to choose their tutors at district expense.

The bottom line: Urgent efforts to improve education for students with exceptional needs will benefit all students, the report said. “There can be no excuse for failing to adopt them on a large scale. National, state, and local leadership must step up, provide targeted support, and hold institutions accountable.”

The 74 recently ran an article titled Fewer Students, Crumbling Buildings: Columbus Looks to Shut Schools Again: Ohio district has tried to downsize, and failed, twice since 2016. But with 113 schools and just 45,000 students, officials have tough choices to make. The story notes a long-term trend toward enrollment loss in the Columbus, Ohio, district school system, and in particular casts an old, never renovated, and under-enrolled Columbus school called Como Elementary as a bit of a victim of a competitive Ohio K-12 environment. The article features another school called Hamilton that is two miles away. Should we however view Como Elementary’s reduced enrollment as a tragedy, or alternatively a triumph?

Como has a capacity of 400 students but sits at 243 students. Hamilton, which unlike Como has been renovated, has a capacity of 575 students but sits at 400.

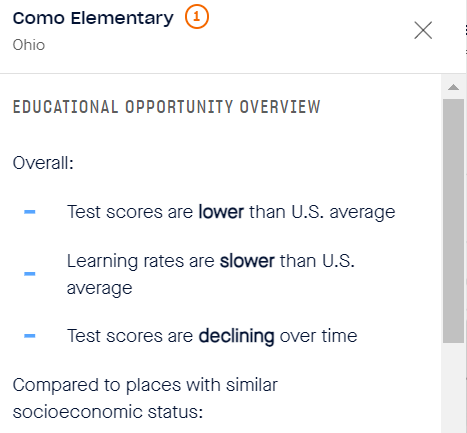

Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Project linked state testing data from across the country in grades three through eight, and currently for the years 2008-2019. If you were something like a charter school authorizer trying to decide whether to renew district schools, you would want to consider additional sources of information, but let’s start here. How well did Como Elementary perform in core tasks of teaching literacy and numeracy to students?

Lower scores, slower learning rates and test scores declining over time is not the hat-trick any school would want. The most problematic of all these statistics: a rate of academic growth that stood at 33% below the national average for the period covered:

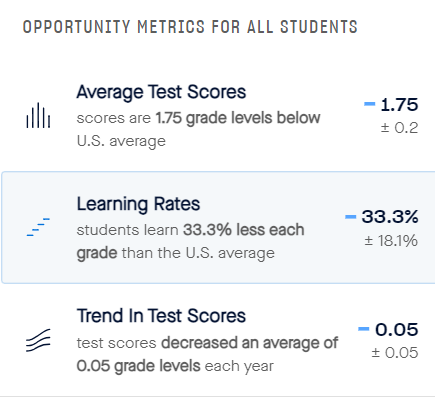

Unfortunately, Como Elementary is not the Columbus school with the slowest rate of academic growth, and it has plenty of competition for the dubious “taught our students the least” crown. Now we get back to the facilities part of the story:

So right about now you might be thinking, rational human that you are dear reader, that the obvious solution here would be for the Columbus school board to close a number of underenrolled and low performing schools to right-size the districts. Drive more money into the classroom, that sort of thing. Hamilton for instance, just two miles away has space for 175 students, and an academic growth rate just 5% below the national average, not great but far better than Como.

Before you go thinking “this is EASY!” allow me to warn you that you are bringing your technocratic scimitar to a political gun fight.

School districts, while nominal democracies, have proven to be easy prey to regulatory capture by unionized employee interests. This is especially the case in large urban districts like Columbus. The main goal of unionized district employees is to preserve the jobs of their members, followed closely by increasing the number of jobs for their members. Closing district schools is not on the agenda. In addition, the general public tends to grab their pitchforks and torches on their way to school board meetings if when a district closes a school in their neighborhood, regardless of how many decades it spent miseducating students.

Oh course our dear friends in the K-12 traditionalist community would like to turn off all this nasty choice business so that Como Elementary can get the students and funding it needs to live happily ever after. A quick look at the Stanford data however reveals that Columbus charter schools are far more likely to have above average academic growth rates than the district schools. And oh, by the way, they are did it with far less funding per student.

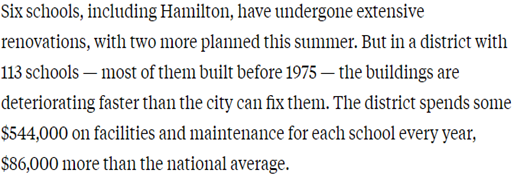

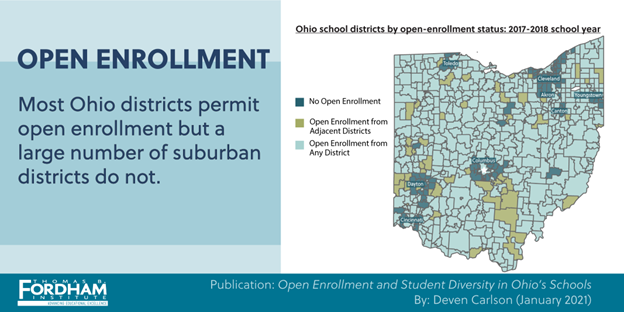

Given that Como Elementary taught their students at a rate 33% below the national average, I’m not inclined to think that it is a tragedy that they only have 243 students. It seems more like a tragedy for those 243 students to have to attend such a low performing school. Where do the seats lie for students attending such poor performing schools lie? In part, with the right mix of policies, out in the blue donut surrounding Columbus:

Unfortunately, Ohio legislators passed a private choice expansion last year that will offer the higher-income residents of those Columbus suburbs only a trifling amount of funding on a per pupil basis. I’m willing to wager that the vast majority of these folks will opt to remain with their gated community district schools, given that they are funded are funded as much as twenty times the rate as the choice program. This feature of Ohio’s voucher law is unintentionally denying opportunities to low-income urban students.

Ohio had been making some progress on addressing the problem illustrated so powerfully in the above map- removing geographic restrictions on charter schools for example. Hopefully they’ll rethink a feature of their voucher program that seems likely to cement economic segregation in schooling in place.

Don’t misinterpret any of this as “Como Elementary Delenda Est.” I have no idea how many district schools should operate in Columbus Ohio. I merely a preference for putting families in the driver’s seat of making the decision on which schools survive.

Editor’s note: We’ve made the point many times: Public education shouldn’t be synonymous with public schools and increasingly, in this age of rapidly expanding options, it isn’t. In a new essay, James V. Shuls, the education policy analyst at the Show-Me Institute in Missouri, expertly riffs on that theme, using the moving story of a student growing up in a tough stretch of St. Louis as a hook. Here’s a taste:

As a child, Korey attended St. Matthew Catholic Church. In 2001, St. Matthew’s parish opened De La Salle Middle School. The small private school above Big Mo’s barbeque restaurant only had 20 students. Korey did not know what to think about the idea of attending De La Salle. In time, he would come to realize that this decision changed his life. With expected pride, he says, “De La Salle put me on a path to greatness.” This school was diferent from other schools he had attended. Class sizes were small, with more one-on-one attention. His teachers were passionate, not just about academics, but also about character. One in particular, Martha Altvater, pushed him harder than he had ever been pushed. From De La Salle, he earned a scholarship to Christian Brothers College (CBC) High School, a respected private school in Saint Louis County, and then attended Westminster College in Fulton, Mo. In 2012, he graduated with a degree in business administration; sitting in the audience was none other than Martha Altvater.

At a critical moment in his life, Korey had the opportunity to attend either a public school or a private school. He chose to attend the private school. In doing so, he chose the option that best served the public, as well as him. Had he chosen the neighborhood public school, Korey says he “might have fallen in with the wrong crowd and be in jail or dead today.” That has been the fate for many of his friends who attended the public high school. But Korey’s fate was different because he found a school that recognized and developed his potential.

Though it is a private school, De La Salle Middle School serves the public much more efectively than the district-run school, where fewer than half of the students graduate. However, instead of celebrating De La Salle as a venerable public institution, we label it as a private school and deem it unworthy of public funds.

***

This essay should not be construed to say that all private schools are great —they are not. Nor should readers think that I am saying that all public schools are bad — they are not. The point is that all types of schools — district, charter, and private — can effectively serve the public. Right now, however, we have put up an artificial barrier that prevents students from using public dollars to attend the private school of their choice. Never mind that these private schools can, as was the case for Korey Stewart-Glaze, serve the student and the public very well.

Korey Stewart-Glaze’s journey has come full circle. He now recruits students to attend the school that changed his life, De La Salle Middle School. Still, funding makes this a somewhat difficult task. Though the school provides privately funded scholarships to 100 percent of its students, they still have to pay some tuition. This severely limits the number of students the school can serve and creates a barrier for many families who simply cannot bear the cost. Our narrow definition of public education prevents De La Salle from receiving state dollars and prevents more students from experiencing the life-changing moment that Korey had. It is time we redefine public education. It should no longer mean assigning students to a specific type of school, regardless of quality, but rather that we provide access to a quality education, regardless of the type of school delivering that education.

A recent headline in the Charlotte Observer offers inspiration this season. “Compete and cooperate,” the newspaper wrote of charter, district and private schools there, “A new direction for Mecklenburg schools.”

This is not a fictional account and it turns on a basic truth about education reform: Despite the caverns that sometimes separate those who are loyal to the great institution of neighborhood schools and those who fight to expand the menu of learning options, the collective effort is still pulling in the same direction. Both believe in the social necessity of public education and both want to give every child the best chance to succeed.

This is not a fictional account and it turns on a basic truth about education reform: Despite the caverns that sometimes separate those who are loyal to the great institution of neighborhood schools and those who fight to expand the menu of learning options, the collective effort is still pulling in the same direction. Both believe in the social necessity of public education and both want to give every child the best chance to succeed.

So allow me to wish this season for fertile and productive common ground, and begin it with a salute to Kevin Welner, professor of education and director of the Education and the Public Interest Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder. His center is known for its allegiance to traditional schools and its steadfast rejection of most, if not all, alternatives to them. Welner is known, in part, for a book that treats tax credit scholarships for low-income schoolchildren as an assault on public education, that dismisses them as “a distraction away from proven solutions and real needs,” and includes the memorable line: “The inherent value of choice should … not be overstated.”

Needless to say, Dr. Welner has a different definition of public education than suits my tastes, but his recent column on Huffington Post made a perfectly legitimate point: Many politicians do use the term “school choice” as a catchall phrase that skips over the educational design and value of individual choice programs. Those on the extremes tend to view choice as though it is either an inherent blessing or evil.

As such, Dr. Welner writes: “There can be a true value in parental choice – matching, for example, a child's interests with the focus of a school. But in making policy we shouldn't assume school choice has some magical power. … Like most tools, school choice can be used in beneficial as well as damaging ways.”

Agreed.

In fact, Dr. Welner’s words sound so much like those of Howard Fuller, the former Milwaukee school superintendent and national leader in the arena of parental choice, that I share a few from redefinED last year: (more…)