Education Next published a piece recently by Holly Korbey called The Tutoring Revolution, which reads in part:

Recent research suggests that the number of students seeking help with academics is growing, and that over the last couple of decades, more families have been turning to tutoring for that help. Private tutoring for K–12 students has seen explosive growth both nationally and around the globe. Between 1997 and 2022, the number of in-person, private tutoring centers across the United States more than tripled, concentrated mostly in high-income areas like Brentwood. Many students are also logging onto laptops to get personalized digital tutoring, with companies like WyzAnt and Outschool reporting they’ve enrolled millions of students for millions of hours in private, video-based learning sessions that students access conveniently from home. Market reports estimate the digital tutoring market was worth $7.7 billion globally in 2022, with projections of a compound annual growth rate of nearly 15 percent from 2023 to 2030.

Recall as well one of the most fascinating parts of Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story podcast series wherein Lacey Robinson, a veteran teacher in inner-city public schools described taking a teaching position in the suburbs. Robinson wanted to learn what the suburban schools were doing to teach literacy to upper-income students, and then bring it back to the inner-city schools. She discovered that the suburban schools were providing their students with approximately nothing:

“They were learning to decode at home with tutors. I know, because I became one of them.”

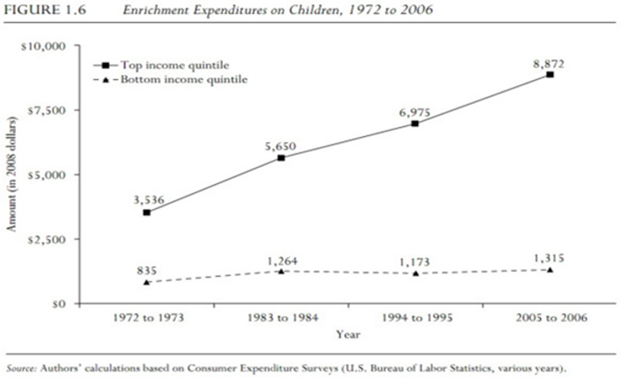

If you speak with or poll American suburbanites, they have traditionally expressed a fair degree of confidence in their public schools, which they tended to describe as either “okay” or “good.” Monitor their actions over time, however, and you see that they placed a greater and greater reliance upon tutoring. Most were enrolling their children in public schools, but they were relying upon them less and less and upon tutoring and other private enrichment spending more and more.

In 2015 Wired ran an article called The Techies Who Are Hacking Education by Homeschooling Their Kids. The unstated background message of this article: Silicon Valley families had decided that the time opportunity cost of enrolling their children in a school, even a public school they had already paid for with their taxes, was too high. Key quote:

“There is a way of thinking within the tech and startup community where you look at the world and go, ‘Is the way we do things now really the best way to do it?’” de Pedro says. “If you look at schools with this mentality, really the only possible conclusion is ‘Heck, I could do this better myself out of my garage!’”

Your garage, and perhaps your local Kumon, museums and hackerspaces. Early during the pandemic, Silicon Valley families created a Facebook group called “Pandemic Pods” with spontaneous order scratch to a very itchy group of American families.

The COVID-19 pandemic opened the eyes of many families regarding how much responsibility they should take for the education of their children: all of it. The public school system operates in the interests of its major shareholders (i.e., those deciding school board elections). Broadly speaking, mere taxpayers and families don’t qualify. One can describe the public school system as broken, but you can more precisely observe that it is operating as intended.

If you doubt that last statement, I invite you to attempt to lobby for a meaningful change in the way the public school system operates. You’ll meet all kinds of interesting people. Sadly, most of them will be eager to die on a hill defending the K-12 status quo.

If someone purposely designed an education system to generate inequality, they would have some difficulty exceeding the ZIP code assignment plus tutoring for those who can afford it status quo. The question moving forward is not whether we are going to have more a la carte multi-vendor education. The question is what, if anything, we are willing and able to do to distribute that opportunity.

Milton Friedman first proposed giving families control of their children’s public education dollars in his 1955 essay "The Role of Government in Education." Friedman argued that the best way to improve student learning was to make the public education market more effective and efficient, and this could happen only if families were empowered to choose their children’s schools. Friedman believed the quality and efficiency of schools would improve if they had to compete for customers (i.e., families) rather than the government assigning families to schools. He further believed that a market-driven public education system would be more equitable and especially benefit lower-income students.

Wisconsin state Sen. Polly Williams was a Black Democrat from Milwaukee who in the late 1980s wanted to help lower-income and minority students attending what Williams described as “failing schools.” Like Friedman, Williams’ solution was school choice, but her approach differed. While Friedman’s market solution was designed to improve the entire public education system, Williams’ focus was not systemic improvement. Her intent was to help lower-income and minority students trapped in failing district schools by giving them public funds to attend private schools.

Williams’ vision became reality in 1990 with the passage of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP), which became the nation’s first publicly funded school choice program. Willams’ approach, which became known as the social justice model of school choice, emerged as the prototype that most school choice advocates and state legislatures embraced for the next 20 years. A small and persistent group of school choice advocates continued to promote Friedman’s market solutions, but social justice remained the dominant school choice rationale.

The first steps toward the merging of the Friedman and Williams models of school choice began in 2011 when Arizona passed the nation’s first education savings account (ESA) program, and in 2014 when Florida began creating the country’s largest ESA programs.

ESAs are flexible spending accounts that families may use to pay for a variety of education products and services in addition to private school tuition and fees.

Jack Coons and Steve Sugarman were among the first to advocate for a voucher with ESA-type functionality when they called for "divisible vouchers" in their 1978 book, Education by Choice. Friedman also called for flexible spending vouchers in a 2003 interview with Education Next.

By enabling families to spend their public education funds on education products and services beyond schools, ESAs allow the supply side of the public education market to expand, which in turn encourages more families to use ESAs, which in turn causes further expansion of the market’s supply-side, which then causes even more families to use ESAs. This ongoing interaction between supply and demand and the information that is shared through this continuous exchange is key to how Friedman envisioned the public education market better serving all students. Particularly those students Polly Williams was most concerned about.

In 2021 West Virginia created an ESA program with no eligibility restrictions other than age and residency. Eight more states have followed West Virginia’s lead, and today Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Iowa, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Utah also have passed various types of ESA programs with universal eligibility. While these states are not all funding every eligible student who wants a scholarship, their ESA programs are growing the demand side of their public education markets. Florida funded over 405,000 ESAs in the 2023-24 school year.

Moving forward, the merger of Williams’ social justice vision with Friedman’s market-based approach for achieving this vision will accelerate as more states give all their students access to ESAs.

The nine states currently working to implement ESA programs with universal eligibility have work to do before their public education markets successfully address Friedman's and Williams’ social justice aspirations.

Determining the proper barriers to market entry for supply and demand is an ongoing challenge. For example, should ESA-funded tutoring be limited to state certified teachers, or is that too restrictive? Should ESA-funded tutors only be required to pass a background check, or is that not restrictive enough? Should homeschool parents who are teaching their children be able to pay themselves with their children’s ESA funds? If not, are we blocking lower-income families from participating in homeschooling?

ESA financial transactions present another challenge. In some states, they are cumbersome and costly. Requiring detailed documents for reimbursements and reviewing every reimbursement request regardless of the amount is expensive, time consuming, and delays payments to families, which puts undue financial pressure on lower-income families. States need to decide if the benefits of reviewing every ESA purchase, regardless of the amount, are worth the costs.

Information is the lifeblood of every market. Without access to the appropriate information, families cannot make good purchasing decisions and good purchasing decisions is how families teach educators (i.e., the supply-side of the market) what they need and want. States need to determine what information families require to help ensure they are purchasing the most appropriate educational services and products for each child. States should also ensure busy families can easily access this information.

These regulatory issues are challenging because of the magnitude of the transformation the public education market is undergoing in ESA states with universal access, and the contentious political environment in which these market improvements are occurring. But these challenges must be successfully addressed if the Friedman/Williams model for achieving greater equality of opportunity through a more effective and efficient public education market is to succeed.

Students at Pine Lake Elementary, a Miami-Dade County magnet school that focuses on botany and zoology, celebrate Earth Day.

As schools in cities across the United States continue struggling to attract and retain teachers, the nation’s fourth-largest district seeks to carve out a new benefit: better odds for its employees’ children to win coveted seats at highly rated magnet schools.

The proposed Miami-Dade County Public Schools policy is set for a school board vote on Aug. 16, the same day members of the United Teachers of Dade are set to vote on a new labor agreement codifying the job benefit.

The proposal would allow parents and guardians who work for the district to "evoke an employee benefit to increase the likelihood of their child being selected during a random selection process" for district schools of choice.

It would set aside 5% of available space in magnet schools for a separate lottery open only to children of school district employees. Students who did not win seats in the employees-only lottery could also enter the public lottery for the remaining spots in the school.

The revised school choice policy also would give magnet admissions priority to children of honorably discharged U.S. military veterans. State law already requires districts to give priority to children of active-duty service members.

Reserving 5% of available spots in each magnet school for district employees would reach further than common school district policies that allow children of school employees to attend the school where their parent or caregiver works.

Pasco County Schools, in the Tampa Bay area, offers such a perk. Chicago Public Schools, the fourth-largest district in the country after Miami-Dade, sets aside two spots in the entry grade of magnet schools for children of employees who work at the site.

School choice has become commonplace in Miami-Dade. The school district's magnet brochure for the coming school year touts more than 1,000 different magnet and choice programs, and notes that three in four of the district's students now choose the school they attend.

The employee preference proposal drew praise from a top leader with the United Teachers of Dade who called it a “welcome improvement” and morale booster for employees, many of whom toil in low-paid, high-stress jobs.

“Improving the morale of employees is paramount to maintaining high-quality professional educators when so many are choosing to walk away from the profession during some of our most difficult times,” UTD First Vice President Antonio White told school board members during a June meeting.

The proposed policy was also a priority of the teachers union early in the contract negotiations process, said Jude Bruno, communications director for the United Teachers of Dade. The provision is also included in the proposed 2023-2026 contract that is up for a vote by members next month.

Bruno said the plan was to codify it in the contract so that if the school board changes the policy during the contract period, “they have to engage with us.”

Was pandemic learning loss a necessary evil to create a more just society?

One teachers union representative from Richmond, Virginia seems to think so. In an interview with ProPublica, Melvin Hostman, who serves on the Richmond Education Association’s executive board, remarked that “the whole thing about learning loss I found funny is that, if everyone was out of school, and everyone had learning loss, then aren’t we all equal? We all have a deficit.”

When confronted with evidence that learning loss disproportionately affected already-disadvantaged populations, Hostman doubled down, pinning the blame on American society’s intrinsic inequities. “Now people are saying, ‘We’re going back to the way things were before,’” Hostman added. “But we didn’t like the way things were before.”

It’s worth noting that Hostman’s position is extreme and uncommon. The vast majority of educators — including those affiliated with prominent unions — are not only worried about learning loss, but also support traditional methods (like extra instructional time and targeted tutoring) of overcoming it.

However, a disturbing number of union representatives and advocacy groups see the pandemic’s aftermath as an opportunity for social and educational re-engineering. In other words, terms like “learning loss” and merit” are now considered old-fashioned at best and something far more sinister at worst.

If union representatives like Hostman want an honest conversation about reform, they have to stop trying to put lipstick on a pig. School closures were incredibly harmful — particularly for disadvantaged students who needed in-person education the most.

More specifically, learning loss, at least in the 2020-2021 school year, was by no means an inevitability. Kids didn’t fall behind because of structural inequities in the American educational system; kids fell behind because many states and districts made a conscious decision to keep them out of school for extended periods of time.

Salt Lake City didn’t even start reopening their schools until February 2021. Students in other places endured even greater turmoil — for New York City, Washington DC, and many school districts in states like California and Illinois, full reopening wouldn’t come until the 2021-2022 school year.

As a result, private schools, which were much more likely to be open for in-person instruction, saw an influx of students. The greater awareness of alternatives helped fuel parents' demand for more choices and led many states to establish or expand education choice programs.

The results speak for themselves. A Harvard study released last year, which analyzed data from more than 2.1 million students, found that school districts that employed remote learning for longer suffered a higher degree of learning loss. In contrast, students in states like Texas and Florida, which resumed in-person learning as quickly as possible, “lost relatively little ground.”

“Interestingly, gaps in math achievement by race and school poverty did not widen in school districts in states such as Texas and Florida and elsewhere that remained largely in-person,” said Thomas Kane, one of the study’s authors, in an interview with the Harvard Gazette. “Where schools remained in-person, gaps did not widen…where schools shifted to remote learning, gaps widened sharply.”

Taken to their logical end, Kane’s comments directly contradict Hostman’s claim, and confirm that America’s children’s experiences were not “all equal.” Children, many from already disadvantaged backgrounds, were kept out of school unnecessarily and suffered disproportionate learning loss as a result.

I’m not about to claim that the chaos was intentional. I’m sure most school closures were done in good faith, even though the scientific research overwhelmingly backed reopening. However, all policy choices have consequences, and these consequences were particularly severe.

Simply put, Hostman’s claim was just plain wrong. Any debate regarding what to do next must start there.

Garion Frankel is an incoming doctoral student in PK-12 education administration at Texas A&M University. He is a Young Voices contributor, and frequently writes about education policy and American political thought.

SailFuture, a private high school, started as a mentoring program for at-risk youth by teaching them maritime skills through sailing adventures. It recently was named as one of 32 semifinalists for the $1 million Yass Prize to be awarded in December.

Consulting firm Tyton Partners, in collaboration with the Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust, today released a new report, Choose to Learn 2022, that looks at data collected from more than 3,000 K-12 parents and more than 150 K-12 suppliers across all 50 states in the United States.

The report finds that 52% of parents now prefer to direct and curate their child’s education rather than rely on their local school system, and 79% of parents believe learning can and should happen everywhere as opposed to in school alone. Data shows that parents want experiences that make their child happy, above all else, by reflecting their child’s interests and providing individual academic support. However, despite all parents reporting similar goals for their children, regardless of demographics, the study reveals gaps in program participation across income and race. For example, children from underserved backgrounds are nearly two times less likely to participate in learning outside of school than their peers.

Choose to Learn 2022 explores the variety of K-12 options now available to families – inclusive of both in- and out-of-school educational offerings – and how this ecosystem can better reflect families’ broader aspirations for their children. The publication follows recent findings from Tyton Partners’ School Disrupted 2022 series, which highlighted the near 10-percent decline in district public school enrollment due to the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In viewing K-12 through a broad lens, we set out to better understand the issues impacting every family, including more than forty million parents who send their children to public school,” according to Christian Lehr, Senior Principal at Tyton Partners and the lead author of Choose to Learn 2022. “Relative to issues of equity and access, our local public districts play a crucial role for K-12 families. At the same time, families crave a wide variety of learning experiences. It is in this spirit that we examined parents’ aspirations at the intersection of in- and out-of-school learning, and ask: How can the K-12 sector deliver a stronger union of academic, extracurricular, and personal outcomes for all families, regardless of life or economic circumstances?”

Based on these findings and more identified in this study, it is clear now more than ever that parents want an education centered on the needs of their child, yet there is continued work that needs to be done to bridge the gap between aspiration and reality. It is incumbent upon the K-12 system of policymakers, system leaders, and suppliers to introduce new experiences, choices, and outcomes into local school districts and catalyze the growth of programs outside of school and across all demographics.

Choose to Learn 2022 underscores the need for the K-12 system to move towards a more student-centric future and helps readers understand how to:

“We are honored to have the opportunity to drive this pivotal conversation forward, alongside our partners, the Walton Family Foundation and Stand Together Trust,” according to Adam Newman, Founder and Managing Partner at Tyton Partners. “There is a clear call for us to collectively build towards a more student-centered future in K-12 education.”

To view the findings and learn more about this study, download Choose to Learn 2022 on the Tyton Partners website.

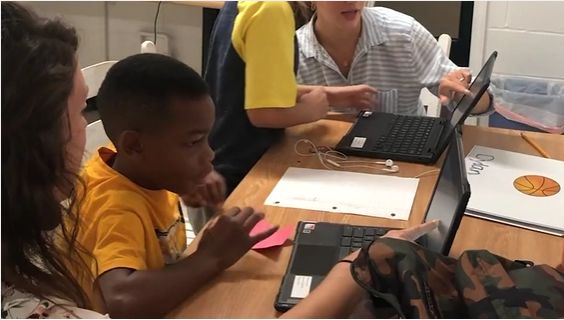

Students study in a pandemic learning pod organized by a group of South Carolina churches, business, nonprofits and individuals in underserved communities.

As the pandemic gripped the nation in the spring of 2020, American schools shut down and sent students home to finish the semester through online learning. The hastily organized programs were thought to be short-term solutions.

But as the rising numbers of coronavirus cases ended administrators’ hopes of fully reopening in the fall, Allan Sherer, a member of the pastoral staff at an Upstate South Carolina church, saw trouble ahead, especially for low-income minority students who had suffered academically in the spring.

The effort Sherer and his church made to educate low-income students over the course of the past two years received national recognition, placing as a semi-finalist for a $1 million STOP Award from Forbes Magazine and the Center for Education Reform.

Sherer’s North Hills Church, a non-denominational suburban congregation that draws 2,000 weekly worshipers, had sponsored academic summer camps for the past nine years. These camps focused on students in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods with the goal of preventing the annual summer learning slide. Now, with the pandemic sending students home permanently, Sherer feared these disadvantaged students in would suffer learning losses so steep that they would never recover.

“We heard numerous stories of children who, when sent home with Chromebooks, never even turned those Chromebooks on,” said Sherer, who has overseen local and global outreach for 15 years at the church in Greenville, S.C. The Palmetto State’s sixth-largest city, Greenville has a population of 70,720 and includes former textile mill villages that sit one county away from BMW’s first North American manufacturing plant, which has brought more than 11,000 jobs and contributed other economic development to the state. Still, intergenerational poverty remains an issue.

After seeing stories about how affluent families were banding together and hiring teachers to deliver in-person instruction to their kids, Sherer immediately thought, “Why shouldn’t children who do not have the means for pods like this also be served?”

Allan Sherer, pastor of missions and outreach at North Hills Church and leader of pods project

Sherer’s vision quickly led to the start of Come Out Stronger, an initiative to offer learning pods in the most underserved communities of the city. North Hills already had relationships with churches in those communities, including Black churches, community organizations and individuals committed to making a difference.

Less than six weeks later, the group raised more than $300,000, identified more than 40 staff members, and set up 10 Covid-compliant locations, each of which was able to serve as many as 24 public school virtual learners.

Sherer said the initiative succeeded because of two major factors: an unprecedented awareness of the intractable gap minority and low-income families face; and a unifying belief that those who have the least opportunity receive an excellent education. The fact that so many community members stepped up in a state that flew the Confederate battle flag on the statehouse grounds until 2015 is a testament to the efforts made toward racial progress in recent years.

“As a faith-based institution leading the way in this initiative we found no resistance or even hesitancy among businesses, public school administrators, predominantly white or African-American churches, and other community stakeholders to coalesce around doing whatever it takes to make sure children were not irreparably left behind,” Sherer said.

In Judson Mill community, which derives its name from the former textile plant there, 76% of children live in homes below the poverty line, placing it in the lowest .3% of comparable communities in the United States. Organizers identified it as a great place for a pod, and the community came together to help make it and other pods a reality.

A regional gas station chain provided financial support while also providing breakfast each day. The lead counselor in the community’s Title I school went door-to-door to persuade parents to place their children in the pod. A Black church offered its building and recruited volunteers of color to help. A white Presbyterian church supplied “a phenomenal reading specialist” who tested each student at the beginning of the school year, laid out personalized plans for reading development and then re-tested students at the end to gauge progress.

“Every child experienced significant reading improvement over the course of the year,” Sherer said.

Each pod was designed to serve 12 children at one time, with one group attending Monday and Wednesday and the other attending Tuesday and Thursday. Students arrived each day at 7:45 a.m. Trained staff helped children log into their school e-learning platform and stay on task with their work. The pods also provided tutoring, structure, snacks, and recreation. Most ended at 2 p.m. Each pod had a budget of $25,000.

The biggest challenge, Sherer said, was the uneven and inconsistent delivery of virtual learning.

For example, one first-grader was expected to log into four different learning platforms to complete her work. Each platform had its own log-in routine and its own method of completing and uploading work.

“This child lives with her grandmother, who cares for three other primary-age children,” Sherer said. “The challenge of navigating these platforms was immense.”

Sherer said establishing standard performance metrics also proved difficult.

“Because of the chaotic nature of the school year, with schedules shifting and children at times coming in and out of our pods it was not feasible to create an evidence-based measure of our success,” he said. “Anecdotally, we have dozens and dozens of stories of children who had never been successful in school who made the A-B honor roll.”

A few examples of that success can be found in the personal stories shared by staff on a video.

One student, described as a “quiet hoodie kid” who had nothing to say, came from a single-parent home and claimed affiliation with a local gang. His grades were all failing.

“We began to speak to him and love him and tell him who he could be,” said staff member Miriam Burgess. She said being around her son, who works in the pod, offered the student a positive male role model.

Within a couple of weeks, his “F’s” became “B’s” and “A’s” and he started talking.

“Now he runs through the pod like he owns it,” Burgess said. The boy’s mother told Burgess that he renounced his gang affiliation and “his whole demeanor is different.”

When another student joined one of the pods, he had been to class only four times since the beginning of the pandemic. He had forgotten how to read, did not know his math facts, and could not remember the order of the alphabet.

“He has gone from reading 35 words per minute to 102 words per minute,” said pod staffer Brittany Meilinger.

Then there were the three siblings who were in the custody of grandparents who also were raising a set of kindergarten twin siblings.

“Their grandmother had no hope of keeping up with all five children and their assignments,” pod staffer J.P. Camp said. “The pod has been life-changing for this family.”

Success stories like those earned the project a place on the list of 20 semi-finalists for the STOP Award. Sponsored by the Center for Education Reform and Forbes, it awarded a $1 million prize to an education provider, exceptional group of people, or organization that demonstrated accomplishment during the coronavirus pandemic by providing an education experience that was “Sustainable, Transformational, Outstanding, and Permissionless.”

Despite the success, Sherer’s pandemic pods ended when local schools reopened in August 2021. Although the pods were closed, church volunteers continued their work in education, logging more than 400 tutoring hours at local public schools so far this year.

Sherer said the experience offered valuable insights about the future of education and inspired the Greenville pod organizers to think even bigger.

The coalition is now working to open a network of private, hybrid, community-based schools that will serve the poorest regions of South Carolina.

“These smaller networks have the potential to drive a new era of innovation. We are re-imagining the entire in-person learning experience, and our partners are lining up,” Sherer said.

Editor’s note: Doug Tuthill responds today to a post I wrote yesterday about the failure of school districts and teachers unions to enact meaningful differential pay plans for teachers – and how that’s indicative of a bigger failure to help low-income students.

Ron, you raised some excellent points in your blog post about the unwillingness of the Pinellas County, Fla. school district to provide each student with equal access to a quality education. For nine years, I received supplemental pay to work in a magnet program that served the district’s academic elite, and for 11 years I was a leader in the local teachers union, which was complicit in the district’s refusal to provide equal opportunity. So your criticisms stung, but they were accurate.

This may be self-serving, but I’m convinced the cause of this leadership failure is not bad people, but an organizational structure and culture that favors the politically strong over the politically weak.

Growing up in Pinellas, I attended segregated public schools. When the federal courts finally forced the school district to desegregate, the focus was on ratios and not learning. The district closed most of the black neighborhood schools and bused those children to schools in the white neighborhoods because busing white students into black neighborhoods was too politically difficult. But white flight meant some forced busing of white students was necessary, so the district created a rotation system that bused low-income/working class white students every two years to schools where the black population approached 30 percent. (The court order said no Pinellas school could be more than 30 percent black.)

While working-class white neighborhoods lacked the political clout to prevent their children from being bused every two years, their protests were loud enough to force the school board to look for alternatives. In the early 1980s, the district started creating magnet programs to entice white families to voluntarily attend schools that were in danger of exceeding the 30 percent threshold.

These magnet programs were designed to provide white students with a superior education. Class sizes were small, textbook and materials budgets seemed unlimited, professional development opportunities were extraordinary and special pay supplements to attract the best teachers were impressive. In my case, when I quit my job as a college professor to teach in the International Baccalaureate (IB) at St. Petersburg High School (SPHS), my annual salary increased 28 percent.

The magnet strategy worked - especially the IB program. Affluent white families began voluntarily busing their children to attend our program, and in many cases students got on buses at 5 a.m. and rode over 50 miles per day to attend.

Unfortunately, desegregation via magnet schools increased the resource inequities that desegregation was suppose to reduce. (more…)