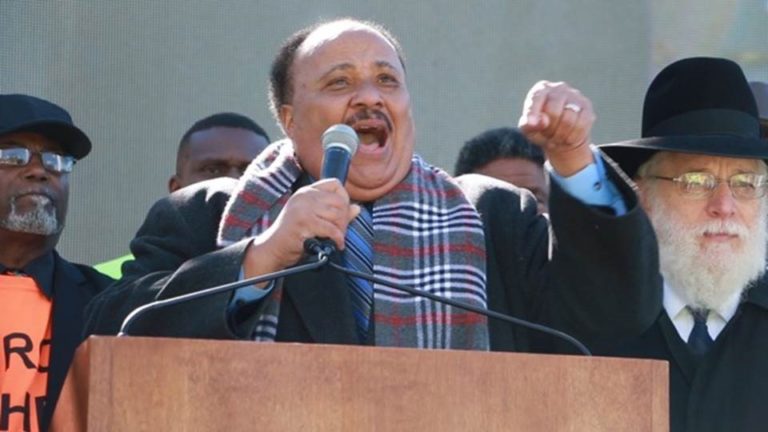

Editor’s note: Seven years ago this week, 10,000 supporters marched on Tallahassee to fight for the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship program, which was the target of a lawsuit backed the state’s largest teachers union and others who opposed the income-based K-12 scholarships. Headlining the parade of civil rights leaders who spoke that day was Martin Luther King III. The younger King has supported education choice, described recently as the civil rights issue of our time, as an extension of his father’s legacy. He has said he sees no reason for it to put public and private school supporters at odds. As for the lawsuit, the Florida Supreme Court rejected it a year later, though efforts to expand opportunities for parents to choose the best educational fit for their children continue. In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, here are excerpts from his remarks. You can watch a video of all the speeches here.

My dad, I don’t really know if I can actually speak to what he would speak today, but I can say is that he would always stand up for justice. This is about justice; this is about righteousness. This is about freedom — the freedom to choose for your family and your child.

My dad told us a lot of things. He used to say that the ultimate measure of the human being is not where one stands in times of comfort and convenience. But where one stands in times of challenge and controversy.

He went on to say that on some questions, cowardice asks: Is the position safe? He said expediency asks: Is the position politic? He said vanity asks: Is the position popular? But that something deep inside called conscience asks: Is the position right?

He went on to say that sometimes we must stand up for positions that are neither safe nor popular nor politic. But we must stand up because our consciences tell us they’re right.

That’s what we are here for today. Because we’re standing on the right side of what’s right for our children …

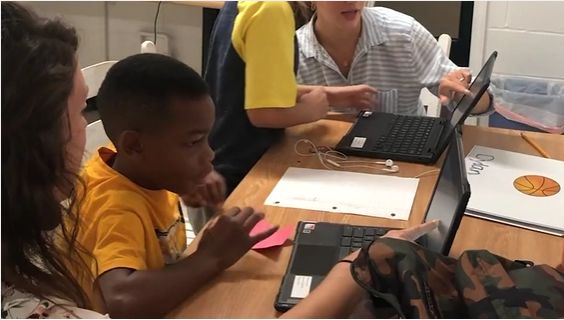

Students study in a pandemic learning pod organized by a group of South Carolina churches, business, nonprofits and individuals in underserved communities.

As the pandemic gripped the nation in the spring of 2020, American schools shut down and sent students home to finish the semester through online learning. The hastily organized programs were thought to be short-term solutions.

But as the rising numbers of coronavirus cases ended administrators’ hopes of fully reopening in the fall, Allan Sherer, a member of the pastoral staff at an Upstate South Carolina church, saw trouble ahead, especially for low-income minority students who had suffered academically in the spring.

The effort Sherer and his church made to educate low-income students over the course of the past two years received national recognition, placing as a semi-finalist for a $1 million STOP Award from Forbes Magazine and the Center for Education Reform.

Sherer’s North Hills Church, a non-denominational suburban congregation that draws 2,000 weekly worshipers, had sponsored academic summer camps for the past nine years. These camps focused on students in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods with the goal of preventing the annual summer learning slide. Now, with the pandemic sending students home permanently, Sherer feared these disadvantaged students in would suffer learning losses so steep that they would never recover.

“We heard numerous stories of children who, when sent home with Chromebooks, never even turned those Chromebooks on,” said Sherer, who has overseen local and global outreach for 15 years at the church in Greenville, S.C. The Palmetto State’s sixth-largest city, Greenville has a population of 70,720 and includes former textile mill villages that sit one county away from BMW’s first North American manufacturing plant, which has brought more than 11,000 jobs and contributed other economic development to the state. Still, intergenerational poverty remains an issue.

After seeing stories about how affluent families were banding together and hiring teachers to deliver in-person instruction to their kids, Sherer immediately thought, “Why shouldn’t children who do not have the means for pods like this also be served?”

Allan Sherer, pastor of missions and outreach at North Hills Church and leader of pods project

Sherer’s vision quickly led to the start of Come Out Stronger, an initiative to offer learning pods in the most underserved communities of the city. North Hills already had relationships with churches in those communities, including Black churches, community organizations and individuals committed to making a difference.

Less than six weeks later, the group raised more than $300,000, identified more than 40 staff members, and set up 10 Covid-compliant locations, each of which was able to serve as many as 24 public school virtual learners.

Sherer said the initiative succeeded because of two major factors: an unprecedented awareness of the intractable gap minority and low-income families face; and a unifying belief that those who have the least opportunity receive an excellent education. The fact that so many community members stepped up in a state that flew the Confederate battle flag on the statehouse grounds until 2015 is a testament to the efforts made toward racial progress in recent years.

“As a faith-based institution leading the way in this initiative we found no resistance or even hesitancy among businesses, public school administrators, predominantly white or African-American churches, and other community stakeholders to coalesce around doing whatever it takes to make sure children were not irreparably left behind,” Sherer said.

In Judson Mill community, which derives its name from the former textile plant there, 76% of children live in homes below the poverty line, placing it in the lowest .3% of comparable communities in the United States. Organizers identified it as a great place for a pod, and the community came together to help make it and other pods a reality.

A regional gas station chain provided financial support while also providing breakfast each day. The lead counselor in the community’s Title I school went door-to-door to persuade parents to place their children in the pod. A Black church offered its building and recruited volunteers of color to help. A white Presbyterian church supplied “a phenomenal reading specialist” who tested each student at the beginning of the school year, laid out personalized plans for reading development and then re-tested students at the end to gauge progress.

“Every child experienced significant reading improvement over the course of the year,” Sherer said.

Each pod was designed to serve 12 children at one time, with one group attending Monday and Wednesday and the other attending Tuesday and Thursday. Students arrived each day at 7:45 a.m. Trained staff helped children log into their school e-learning platform and stay on task with their work. The pods also provided tutoring, structure, snacks, and recreation. Most ended at 2 p.m. Each pod had a budget of $25,000.

The biggest challenge, Sherer said, was the uneven and inconsistent delivery of virtual learning.

For example, one first-grader was expected to log into four different learning platforms to complete her work. Each platform had its own log-in routine and its own method of completing and uploading work.

“This child lives with her grandmother, who cares for three other primary-age children,” Sherer said. “The challenge of navigating these platforms was immense.”

Sherer said establishing standard performance metrics also proved difficult.

“Because of the chaotic nature of the school year, with schedules shifting and children at times coming in and out of our pods it was not feasible to create an evidence-based measure of our success,” he said. “Anecdotally, we have dozens and dozens of stories of children who had never been successful in school who made the A-B honor roll.”

A few examples of that success can be found in the personal stories shared by staff on a video.

One student, described as a “quiet hoodie kid” who had nothing to say, came from a single-parent home and claimed affiliation with a local gang. His grades were all failing.

“We began to speak to him and love him and tell him who he could be,” said staff member Miriam Burgess. She said being around her son, who works in the pod, offered the student a positive male role model.

Within a couple of weeks, his “F’s” became “B’s” and “A’s” and he started talking.

“Now he runs through the pod like he owns it,” Burgess said. The boy’s mother told Burgess that he renounced his gang affiliation and “his whole demeanor is different.”

When another student joined one of the pods, he had been to class only four times since the beginning of the pandemic. He had forgotten how to read, did not know his math facts, and could not remember the order of the alphabet.

“He has gone from reading 35 words per minute to 102 words per minute,” said pod staffer Brittany Meilinger.

Then there were the three siblings who were in the custody of grandparents who also were raising a set of kindergarten twin siblings.

“Their grandmother had no hope of keeping up with all five children and their assignments,” pod staffer J.P. Camp said. “The pod has been life-changing for this family.”

Success stories like those earned the project a place on the list of 20 semi-finalists for the STOP Award. Sponsored by the Center for Education Reform and Forbes, it awarded a $1 million prize to an education provider, exceptional group of people, or organization that demonstrated accomplishment during the coronavirus pandemic by providing an education experience that was “Sustainable, Transformational, Outstanding, and Permissionless.”

Despite the success, Sherer’s pandemic pods ended when local schools reopened in August 2021. Although the pods were closed, church volunteers continued their work in education, logging more than 400 tutoring hours at local public schools so far this year.

Sherer said the experience offered valuable insights about the future of education and inspired the Greenville pod organizers to think even bigger.

The coalition is now working to open a network of private, hybrid, community-based schools that will serve the poorest regions of South Carolina.

“These smaller networks have the potential to drive a new era of innovation. We are re-imagining the entire in-person learning experience, and our partners are lining up,” Sherer said.

“It’s the poor wot gets the blame.”

“It’s the poor wot gets the blame.”

-- Anonymous

There seems a fairly common conviction among us that many, even most, of our lower-income parents, for various reasons, fall below the level of responsibility necessary to decide which school is best for their child.

That belief, though slowly receding, seems yet sufficient to allow a general survival of the 19th Century enrollment policy by which the child is thought to be rescued from the naivete or indifference of the not-so-rich, maybe immigrant, parent. The boy or girl is thus ordered by government strangers into some nearby school called “public.”

Today, armadas of both critics and defenders of this intellectual ghetto of unprivileged children collide over its wisdom. The battle, so far, has been carried on largely over the learning efficiency of this system as measured by number scores on standardized tests.

Blizzards of these snow-report statistics come from states such as Ohio and Florida, which strongly suggests that a moderate growth in the child’s grasp of basics is achieved when choice is subsidized for him or her to attend the parents’ favored school.

Paradoxically – and distractingly – this avalanche of easy-to-report numbers has made test scores seem the essence of choice’s civic gift. In my view, this fixation on tallying scores has distracted the ready audience of choice from the broader and deeper effects to be expected of the re-empowerment of these belittled parents to act like, well … parents.

Mothers! Fathers! You are too poor to be ready to exercise your constitutional right; so, Freddie gets assigned to Lincoln Elementary for eight years.

One clear message from this to parents is hardly subtle. You are struggling to provide, hence, you are unfit to be sovereign of your own children, and, in reality, a mere servant of the state. You have completed your initial five years of duty in this role, producing and nurturing Freddie. That duty continues, but now with added responsibility to this government to deliver him to us at Location X five days a week. You may alter this responsibility only by changing residence or paying private school tuition.

From his next eight years of experience in such relationships, Fredie learns at least one thing: “I don’t want this family thing, ever, to happen to me; it’s a trap. I’m staying free.” Meanwhile, Freddie’s parent has reconceived what had briefly seemed a role of authority and responsibility, not so different from that of the rich. It had suddenly become merely an agency of those strangers who run the state.

At day’s end, if little Alice has complaints about her daily lot at school, what can a poor parent do about it? And what toll does this revelation of personal futility take on the parent’s sense of responsibility? “I can do zero, so I guess that’s what I’ll do from now on.”

If the child and parent have both learned that – unlike the rest of us – parents play only a subordinate role in the raising of the child, what effect has this upon our civil order? Does it make for the ideal of the good citizen to learn that, if you are poor, the State, not the family, will decide how and where and what this child’s mind and spirit will be served?

Could the answer be relevant to the rescue and reuniting of our society?

This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first published on the RealClear Policy blog.

This commentary from Neal McCluskey, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom, first published on the RealClear Policy blog.

A new Gallup poll that surveyed parents with school-aged kids has startling results, much more because of how opinions are split than the opinions themselves.

Given the COVID-19 threat, 36% of parents want their children to receive fully in-person education, 36% want an in-person/distance hybrid, and 28% want all distance. Each mode was preferred by essentially one-third of parents, neatly capturing a now undeniable reality: Families need school choice.

The basic problem is that diverse people have different needs, but a school district is unitary. This is always trouble — diverse people are stuck with one dress code, history curriculum, etc. — but COVID-19 makes the stakes far higher and more immediate than usual. You might be willing to engage in a protracted school board battle to improve curricula, but COVID-19 could put your child’s life, or basic education, in potentially huge danger right now.

In many places, the public schools have taken the side of maximum COVID caution. The school districts in Los Angeles, Chicago, and elsewhere will, at least to start the year, only offer distance education.

That may be fine for kids who learn better at home, have medical conditions that make them high-risk, or who live with elderly relatives. But it is a huge hit to children with poor internet connectivity, learning disabilities, or those who simply thrive in a physical classroom.

It appears that a spontaneous, nationwide eruption of parent-driven, in-person education is the response to such closings. The “pod” phenomenon is perhaps the most buzzy sign of this, generating both fascinated and skeptical coverage in major media outlets. Basically, parents are pooling their money to hire teachers and create closed learning communities for their kids.

We may also be seeing more families moving to traditional private schools, with reports of privates receiving increased interest, and sometimes definite enrollment boosts, around the country. There is no systematic data to confirm a national movement, but the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom has been tracking private school closures connected to COVID-19 since March and has only recorded eight since July 14. This low number may well reflect new enrollments in private schools.

Of course, affording a private alternative can be difficult for lower-income families, and many people worry that the move to private schooling will fuel greater inequality.

Thankfully, there is a solution, and it is straightforward: Instead of education funding going directly to public schools, let it follow children, whether to a pod, private school, charter school, or traditional public. With public school spending exceeding $15,000 per student, most privates, which charge roughly $12,000 on average, would be in anyone’s reach, while families pooling 10 kids could offer $150,000 to a pod teacher.

The Trump administration has been pushing choice, and certainly any federal aid should follow kids. But constitutional authority over education lies with the states, and it is from them that choice should come. Indeed, more than half-a-million children already attend private schools through voucher, tax credit, and education savings account programs in 29 states and Washington, D.C. But that is far below the number who need choice — states that already have it should expand it, and those without it should enact it.

But expanding funding may not be enough to supply the COVID choice people need. In some places, including much of California, public authorities are forbidding many private institutions from teaching in-person. Such prohibitions must be lifted.

These actions may be intended to protect public schools’ pocketbooks. For instance, the chief health official in Montgomery County, Maryland, has said no private school can open until at least October 1, a date right after the enrollment “count day” that determines how much state and federal funding public schools get.

Of course, health concerns may be the only driver of such decisions. But school-aged children appear to face very low levels of COVID danger. According to CDC data, Americans ages 5 to 17 account for fewer than 0.1% of all COVID-19 deaths, and since tracking began, it has accounted for less than 1% of all deaths in the 5-to-14 age group. While increasing safety measures is important, kids appear to face greater dangers than COVID-19.

What about teachers and administrators? Adults are at greater risk than children, but private schools will do many things to protect them, including mandatory mask wearing, face shields, social distancing, improved air filtration, and more. And teachers unwilling or unable to work in-person could choose jobs in online-only schools.

The simple fact is all communities, families, and children are different, and they need educational options reflective of that diversity.