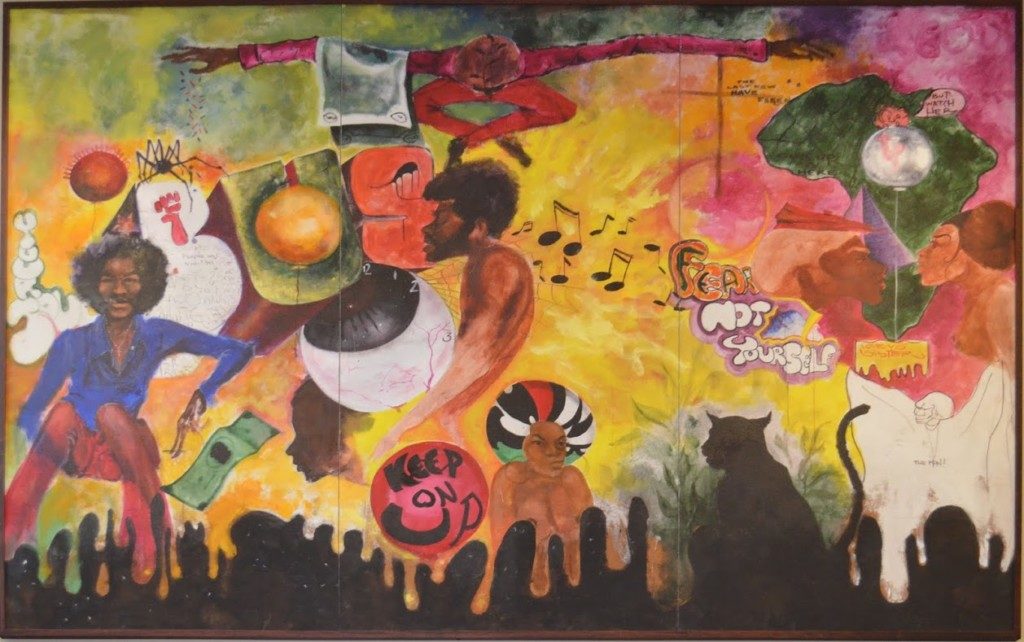

One of a series of murals covering the walls of the Center for Pan-African Culture at Kent State University, dedicated to a group of Kent State students called Black United Students, who first proposed the adoption of Black History Month

Editor’s note: This February marks the 43rd anniversary of Black History Month. President Gerald R. Ford, in the nation’s bicentennial year, urged Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” redefinED is taking this opportunity to revisit some pieces from our archives appropriate for this annual celebration. The article below originally appeared in redefinED in September 2016. Orange Park Normal and Industrial School was memorialized with a historical marker last year during Black History Month.

"We do not refuse anyone on account of race," Orange Park Normal and Industrial School principal Amos W. Farnham wrote to William N. Sheats in the spring of 1894.

In a letter to Sheats, Florida's top education official, Farnham described a faith-based institution in Clay County that was racially integrated 60 years before Brown v. Board of Education. Black and white students went to chapel, ate meals and learned together. Boys at the school, he wrote, "play baseball, 'shinney,' marbles and other games together."

Those words would soon spell trouble for the school, its students and its teachers.

Sheats, who would later be hailed as the "father of Florida's public school system," was an unrepentant segregationist and racist who launched an 18-year campaign to destroy the upstart school. His staunch opposition to racial integration fueled a decades-long crackdown on dozens of schools — many of them private institutions run by religious aid societies. It also inspired laws that subjected Florida to national ridicule and dashed hopes of racial progress after Reconstruction.

Known as the Sheats Law, a Florida statute barring black and white children from being taught in the same school was struck down in court, 120 years ago next month.

A school with a mission

Orange Park Normal and Industrial School was founded by the American Missionary Association (AMA), a protestant abolitionist society, with a mission to educate the children of freed black slaves.

The school took its name from the surrounding town, an enclave of northern transplants just south of Jacksonville on the banks of the St. Johns River. It first opened its doors to 26 students, including 16 boarders, in October 1891. By the fall of 1892, its enrollment swelled to 116 students.

The school provided a primary education for grades 1-8 as well as teacher training, vocational training and college preparatory coursework for older students in grades 9-12. In addition to typical courses of the day such as grammar, rhetoric, mathematics and calisthenics, the school also taught music, stenography, typing, agriculture, botany, horticulture, wood-working and printing. (more…)

"We do not refuse anyone on account of race," Orange Park Normal and Industrial School principal Amos W. Farnham wrote to William N. Sheats in the spring of 1894.

In a letter to Sheats, Florida's top education official, Farnham described a faith-based institution in Clay County that was racially integrated 60 years before Brown v. Board of Education. Black and white students went to chapel, ate meals and learned together. Boys at the school, he wrote, "play baseball, 'shinney,' marbles and other games together."

Those words would soon spell trouble for the school, its students and its teachers.

Sheats, who would later be hailed as the "father of Florida's public school system," was an unrepentant segregationist and racist who launched an 18-year campaign to destroy the upstart school. His staunch opposition to racial integration fueled a decades-long crackdown on dozens of schools — many of them private institutions run by religious aid societies. It also inspired laws that subjected Florida to national ridicule and dashed hopes of racial progress after Reconstruction.

Known as the Sheats Law, a Florida statute barring black and white children from being taught in the same school was struck down in court, 120 years ago next month.

A school with a mission

Orange Park Normal and Industrial School was founded by the American Missionary Association (AMA), a protestant abolitionist society, with a mission to educate the children of freed black slaves.

The school took its name from the surrounding town, an enclave of northern transplants just south of Jacksonville on the banks of the St. Johns River. It first opened its doors to 26 students, including 16 boarders, in October 1891. By the fall of 1892, its enrollment swelled to 116 students.

The school provided a primary education for grades 1-8 as well as teacher training, vocational training and college preparatory coursework for older students in grades 9-12. In addition to typical courses of the day such as grammar, rhetoric, mathematics and calisthenics, the school also taught music, stenography, typing, agriculture, botany, horticulture, wood-working and printing. (more…)

A century ago, three Catholic sisters in St. Augustine, Fla. were arrested for something the state Legislature had recently made a crime: Teaching black children at what, in the parlance of the time, was known as a "negro school."

The ensuing trial propelled a 266-year-old French Catholic order and America's youngest Catholic Bishop into the middle one of the wildest and most racially charged gubernatorial campaigns in Florida history. A hundred years ago today, the white sisters won their legal battle, vindicating the rights of private institutions like the Saint Benedict the Moor School that fought to create educational opportunities for black children in the era of Jim Crow segregation.

Black parents' demand for quality education didn't begin with Brown v. Board, but hundreds of years before, in chains and in secret. But near the turn of the twentieth century, as Jim Crow laws reversed the progress made under post-Civil War reconstruction, public institutions intended to uplift freed blacks became increasingly inadequate and unequal. Black parents often turned to their own churches or to missionary aid societies, like the Sisters of St. Joseph, to educate their children.

The story of the three white Catholic sisters has been examined over the years by multiple scholars, whose work informs this post. And while details in the historical record are at times murky and ambiguous, the episode sheds light on the countless struggles across the South to educate black children who were pushed to the margins by oppressive public institutions.

* * *

Founded in 1650 in Le Puy-en-Velay, a rural mountain town in southern France, the Sisters of St. Joseph took up a mission to serve, educate and care for the poor and disadvantaged. For the next 200 years, the sisters pursued their mission throughout France until they were invited to Florida by Bishop Augustin Verot after the end of the U.S. Civil War.

Founded in 1650 in Le Puy-en-Velay, a rural mountain town in southern France, the Sisters of St. Joseph took up a mission to serve, educate and care for the poor and disadvantaged. For the next 200 years, the sisters pursued their mission throughout France until they were invited to Florida by Bishop Augustin Verot after the end of the U.S. Civil War.

Verot, a native of Le Puy, recruited eight sisters for a new mission: To educate newly freed slaves and their children.

The sisters established Florida's first Catholic school for black students in 1867 along St. George Street in St. Augustine. They would go on to establish schools in Key West and in Ybor City. With the financial backing of a wealthy heiress, Saint Katharine Drexel, the Sisters of St. Joseph opened St. Benedict the Moor School in 1898.

The Sisters of St. Joseph, along with other religious groups like the Protestant American Missionary Association, educated black students in private and public schools in Florida for several decades. But then the legislature lashed out against their efforts. "An Act Prohibiting White Persons from Teaching Negroes in Negro Schools" unanimously passed through both chambers without debate, and was signed into law on June 7, 1913. (more…)