With Gov. Mark Gordon's signature, Wyoming is now the 17th state to place public education funding in the hands of parents.

As he signed HB 166 into law, Gordon struck one of its unique features and called attention to an under-appreciated opportunity for the education choice movement.

Gordon used a line-item veto to limit the program to families earning below 150% of the federal poverty level. Under the bill that passed the Legislature, scholarships would have been available to families with higher incomes, with funding amounts reduced on a sliding scale.

However, Gordon argued scholarships for those families could run afoul of a unique provision in Wyoming's constitution, which says the state cannot "loan or give its credit or make donations to or in aid of any individual, association or corporation, except for necessary support of the poor."

In his message explaining his actions, Gordon also praised a provision requiring the state to set aside a fifth of the available scholarships for preschool students, a significant expansion of early learning in a state with limited publicly funded preschool programs.

“By providing families access to various educational services, including pre-kindergarten programs, the ESA program has the potential to enhance the early learning experiences of children across the state,” he wrote, and as a result, “this legislation has the potential to expand access to high-quality early childhood education for Wyoming’s children, especially those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.”

Targeting younger learners may be an untapped opportunity for advocates in other states looking to give parents more power to direct education funding.

Gordon has also enlisted Wyoming's school districts to design a major overhaul of public education, which includes more opportunities for learning outside the classroom and flexible use of learning time.

“While this legislation may pose challenges for the K-12 public school system, it may also bring the benefits associated with increased competition," he wrote.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Charles J. Russo, Joseph Panzer Chair in Education in the School of Education and Health Sciences and research professor of law at the University of Dayton, appeared last week on The Conversation.

Editor’s note: This commentary from Charles J. Russo, Joseph Panzer Chair in Education in the School of Education and Health Sciences and research professor of law at the University of Dayton, appeared last week on The Conversation.

Since 1947, one topic in education has regularly come up at the Supreme Court more often than any other: disputes over religion.

That year, in Everson v. Board of Education, the justices upheld a New Jersey law allowing school boards to reimburse parents for transportation costs to and from schools, including religious ones. According to the First Amendment, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” – an idea courts often interpreted as requiring “a wall of separation between church and state.”

In Everson, however, the Supreme Court upheld the law as not violating the First Amendment because children, not their schools, were the primary beneficiaries.

This became known as the “child benefit test,” an evolving legal idea used to justify state aid to students who attend religious schools. In recent years, the court has expanded the boundaries of what aid is allowed. Will it push them further?

This question will be in the spotlight Dec. 8, when the court hears arguments in a case from Maine, Carson v. Makin. Carson has drawn intense interest from educators and religious-liberty advocates across the country – as illustrated by the large number of amicus curiae, or “friend of the court,” briefs filed by groups with interests in the outcome.

To the school choice movement – which advocates affording families more options beyond traditional public schools – Carson represents a chance for more parents to give their children an education in line with their religious beliefs. Opponents fear it could establish a precedent of requiring taxpayer dollars to fund religious teachings.

To continue reading, click here.

Portrait of smiling little girl working with plasticine in art and craft class of development school

Editor’s note: This commentary from Amanda Kieffer, communications director for the Cardinal Institute for West Virginia Policy, appeared on projectforeverfree.org.

It’s been a tempestuous couple of years for education reform, but the clouds have broken over 2021, and the silver linings have rarely shown as bright.

Following two years of the Red for Ed movement and two years of COVID mandates and lockdowns that have hobbled the education of a generation of children, fed-up families are finally demanding better educational choices. And lawmakers are listening.

This year alone, 18 states have either expanded existing education choice programs or added new ones. We’re living in the “Year of Educational Choice.” But as the sun rises on a new world, the educational establishment is fighting to keep the old system alive.

In West Virginia, for example, Mountain State Justice (MSJ), a left-leaning public interest law firm, has filed an intent to sue against the state’s brand new Hope Scholarship — the nation’s broadest and most inclusive education savings account.

The program gives families 100% of the state-based portion of education tax dollars, estimated at $4,600 per child per year, to use on whatever kind of education they please.

Students who want to stay enrolled in their traditional public schools and students who wish to leave full-time enrollment in the traditional public school system can use the scholarship funds to pursue a more individualized education. Families can use the Hope Scholarship for tuition, curriculum, educational materials, special needs therapies, tutoring, and more.

In short, the scholarship gives families some choice as to what education they’d like to pursue and allows them to take their tax dollars where they will. The scholarship may not cover the entire cost of tuition, but it will lessen the financial burden for families.

That doesn’t sit well with MSJ. Their suit contests the scholarship on anti-discrimination grounds, stating that it “excludes anti-discrimination protections otherwise protected under state laws.” They also allege that the new program takes money from public schools without making up for the money in the school budget.

To continue reading, click here.

Editor’s note: This post from Malka Kownat-Rhodes, a longtime professional in the special education field and a school funding specialist with Teach Florida, appeared Thursday on Florida Politics.

Editor’s note: This post from Malka Kownat-Rhodes, a longtime professional in the special education field and a school funding specialist with Teach Florida, appeared Thursday on Florida Politics.

One of the hottest topics of debate in the Florida legislative session was school choice legislation. For all the back and forth leading up to the passage of SB 48/HB 7045, legislators deserve our thanks for including a key group the proposal will affect: working-class families like mine, who desire a particular kind of education that their children simply can’t get in public schools.

We now look to the governor to finalize this progress by signing the measure into law.

My husband and I work hard to provide a good life for our twin 9-year-old boys. My grandmother survived the horrors of Auschwitz while remaining steadfast to her Jewish values and traditions, and we wanted to cling to that heritage and pass on our faith’s traditions to our children. That was at the core of our decision to send them to a school with both a strong Jewish and secular education.

So much of the school choice discussion in Tallahassee was over whether, and how, the state should help kids attend private schools. But that debate isn’t the central focus for a large group of families where both parents work so they can make ends meet but still want something for their children that public schools cannot provide. Paying for our sons’ schooling isn’t easy, but it’s so very important to us.

To continue reading, click here.

Included in an array of legislative proposals aimed at improving educational outcomes for Florida’s students are two that focus on early childhood learning and literacy.

On Tuesday, the House PreK-12 Appropriations Subcommittee approved legislation to establish a statewide program to deliver free books to elementary-school students identified as struggling readers.

HB 3, sponsored by Republican State Rep. Dana Trabulsy would be Florida’s first book distribution plan to provide at-home literacy support for students reading below grade level. The plan would feature the New Worlds Reading Initiative, delivering one free book each month for nine months of the year.

At least 557,344 elementary school students would be eligible to participate in the initiative according to an analysis of the bill.

Trabulsy acknowledged that cost of the initiative is unknown; funding, including purchase and delivery of books, would depend upon an appropriation provided by the Legislature in the Fiscal Year 2021-2022 General Appropriations Act.

Earlier today, the House Early Learning and Elementary Education Subcommittee unanimously advanced legislation designed to overhaul and update how voluntary prekindergarten providers are evaluated. HB 419, under the leadership of Republican Rep. Erin Grall, would establish a timeline for phasing in a new VPK accountability system based on a performance metric that includes student outcomes, learning gains and observations of child-teacher interactions.

The measure is backed by the Florida Chamber of Commerce, which has long supported accurate and appropriate metrics to evaluate student progress. To prepare for this continued growth, the Florida Chamber Foundation’s 2030 Blueprint established a goal that 100% of Florida’s children will be kindergarten-ready by 2030.

A recently filed bill that would shift the cost of dual enrollment from private schools to the state would benefit schools like Center Academy in Pinellas Park, one in a network of 10 schools across Florida that serve students with learning differences.

The staff at Center Academy used to encourage eligible high school students to enroll in classes through Florida’s dual enrollment program. Not only did it pave the way for those students to get a head start on college; it boosted their confidence and allowed any with reservations if college was the best fit after graduation.

But a loophole in state law that made dual enrollment prohibitively expensive for private schools forced Center Academy and others to limit participation – or not offer the program at all.

“Our students would have a chance to be successful, but we don’t want to offer dual enrollment because the cost makes it difficult for us to operate our school, especially if every student took advantage of the program,” said Steve Hicks, vice president of operations for the Pinellas Park-based network of 10 schools across Florida that serve students in fourth grade through high school with learning differences.

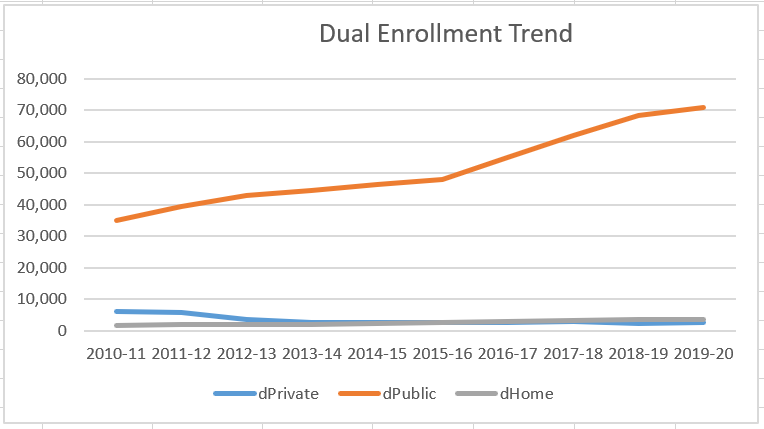

Recent figures from the Florida Department of Education show the inequity that the loophole created has worsened over time, with the number of private school students participating in dual enrollment declining 60% over the past 10 years. District schools, meanwhile, more than doubled the number of dual enrollment students during the same period. Home schoolers also saw their dual enrollment numbers more than double.

At the same time, the number of lower-income students attending private schools on Florida Tax Credit Scholarships more than quadrupled, putting more lower-income students at an even greater disadvantage.

At the same time, the number of lower-income students attending private schools on Florida Tax Credit Scholarships more than quadrupled, putting more lower-income students at an even greater disadvantage.

“For years, private school students have had this stumbling block,” said Michael Barrett, who oversees education policy issues for the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops. “Everyone should have equal access to education. We have 30,000 students on state scholarships and over 22,000 on (income-based) scholarships who could benefit from accelerated college educations while in high school.”

“For years, private school students have had this stumbling block,” said Michael Barrett, who oversees education policy issues for the Florida Conference of Catholic Bishops. “Everyone should have equal access to education. We have 30,000 students on state scholarships and over 22,000 on (income-based) scholarships who could benefit from accelerated college educations while in high school.”

The high cost has forced many Catholic high schools to limit dual enrollment participation to college courses that their own faculty members are certified to teach, Barrett said.

Dual enrollment access first became an issue in 2013 when a change in the law shifted the cost of dual enrollment programs from colleges to school districts. Because school districts are state funded, the state picked up the cost. But private schools, which couldn’t pass the cost on to their students, had no alternative but to limit their dual enrollment offerings.

New provisions for dual enrollment that were expected to address the issue were included in a wide-ranging bill, HB 7055, which then-Gov. Rick Scott signed into law in 2018. One of those provisions removed the requirement that articulation agreements – the documents that allow students to take certain classes at nearby colleges — must specify whether the private schools are responsible for tuition. But educators were not clear on whether colleges or the schools would pay dual enrollment costs.

Private school officials waited for clarification from the state Department of Education, but a memo on the bill did not address the provisions. Lawmakers have tried for the past few years to clarify the issue, but proposed legislation never made it to the governor’s desk despite bipartisan support.

Last year, state Sen. Kelli Stargel, R-Lakeland, sponsored SB 1246, which would have established a state scholarship fund to cover the costs incurred by private schools and homeschool students. (The law already bars colleges from charging homeschool students who take dual enrollment courses.) An analysis estimated the cost at $28.5 million.

The bill won approval from the Senate Education Committee but died in the Senate Appropriations Committee. A companion bill filed by state Rep. Ardian Zika, R-Land O’Lakes, also died in committee.

Supporters haven’t given up hope. This year, lawmakers are making another run at changing the law to shift the cost from private schools to the state. SB52, filed last month by state Sen. Ray Rodrigues, R-Fort Myers, is nearly identical to previous versions.

School leaders hope this attempt will prove successful.

“We have always believed that our students who attempt dual enrollment classes will be more likely to attend college and pursue a degree,” Hicks said. “It is great for their self-esteem to take a college course and find success.”

Policymakers have a knack for finding private endeavors they presume still need fixing. The latest example? Learning pods.

Policymakers have a knack for finding private endeavors they presume still need fixing. The latest example? Learning pods.

With many schools closed to in-person instruction this fall, many parents have quickly adapted, developing the pods to continue their children’s education. Now policymakers are catching up with rules and regulations.

Learning pods are loosely defined as small groups of children who gather in a parent’s home for K-12 instruction. If this sounds like homeschooling, that’s because homeschool co-op arrangements like this have existed for decades, allowing parents to hire teachers or share their own subject matter expertise with groups of children who are not attending a public or private school full time.

In the pandemic, these pods are attracting families that had not considered educating their child at home before but are doing so now because of dissatisfaction with district online learning platforms. Parents have reason to be skeptical of district offerings this fall: District e-learning systems crashed or otherwise malfunctioned at the beginning of the new school year in Hartford, Houston, Virginia Beach, Philadelphia, across North Carolina, and during a practice session for families in Seattle.

At a Detroit school, a teacher expecting 14 students to attend online only had one student login, and his headphones were not working.

Carrie Limpert-Bostrom, a Minnesota parent, said in an interview, “You are able to fit it [a pod] to your specific needs. In our case, we wanted somebody who could speak French and speak to our children.”

She says she does not blame her school district because information regarding the pandemic is changing all the time. But, she says, “I knew I wanted something as stable as possible for my child,” adding, “I’m taking control of my daughter’s education during this time.”

Yet in some states, the question of who, in reality, is in control is one for the bureaucrats.

In Pennsylvania, state officials issued regulations stating that families involved in pods with six or more children must "notify" a state agency. While the groups do not need to be licensed, pod families must have evacuation plans in case of an emergency, as first reported by Reason, as well as create their own “health and safety plans.”

South Carolina officials are requiring that pod families serving more than six children apply for a family childcare home license. According to Charleston media, “local zoning regulations could limit that number further.” These reports also say at-home visits will be required. By the end of August, Connecticut companies helping parents form pods area ware of the potential for regulations (with the state department of education having released guidance for at-home learning) and have already scheduled “inspections” for homes hosting pods in West Hartford and Ellington (located north of Hartford).

In Oregon, where lawmakers blocked virtual charter school enrollment at the beginning of the pandemic, officials said they may regulate pod families in the same way as childcare providers. Such restrictions would include requiring background checks, CPR training and safe sleep training.

Governors in Colorado and Massachusetts have announced waivers for traditional childcare regulations to allow the formation of pods, but these executive orders still limit the size of each pod. The Massachusetts waiver will help organizations offering after-school programs, but parents are prohibited from paying each other for either their time or the use of a home.

Many state legislators will not return to session until the beginning of next year. This fall, state agencies should not be allowed to apply restrictions on learning pods — including in-home visits. Governors should look for ways to waive regulations and licensure requirements that would limit parent attempts to provide an education for their children. Public and private school educators can determine ways of measuring student progress if students choose to return to schools, but policymakers should not regulate pods like daycare centers in the meantime.

Next year, state lawmakers can align state policies on homeschooling, private schools, and other private learning options such as education savings accounts or K-12 private school scholarships with pods and micro-schools so that parents can make informed choices about the best learning option for their child.

Until then, parents should be encouraged to customize their child’s learning experience while district plans remain in flux.